by Keith Harwood

Although it is not regarded as politically correct nowadays, the taxidermist’s art is something for which I have always had a fondness. A well-mounted fish or bird is to me a thing of beauty. The walls of my study are adorned with a Windermere pike in a bow-fronted glass case and another case containing a brace of pheasants: a cock and hen bird. Each case or mount has a story to tell, and it saddens me when I see cases of fish coming up for auction that will eventually end up on the wall of a collector or hotel, with no connection whatsoever to the original captor. For an angler to go to the trouble (and not inconsiderable expense) of having a fish set up suggests that its capture meant a great deal to him or her and was almost certainly a personal best at the time. Once that fish is sold, the circumstances of its capture will probably be lost. Fortunately, however, it is sometimes possible to reconstruct the story of a cased fish, as the following example proves.

Over the course of the last two or three years, I have fished on a number of occasions at Malham Tarn, a glacial lake situated in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales. The lake itself is 377 meters above sea level and is reputed to be the highest lake in England. The estate on which the tarn is situated is owned by the National Trust, which leases it to the Field Studies Council, which offers field courses at Malham Tarn House. The tarn is no longer stocked but is home to some large wild brown trout and perch. Bank fishing is not allowed, and anglers wishing to fish this fly-only water must hire and fish from one of the estate’s four boats. Anglers used to fishing on well-stocked reservoirs find the tarn extremely challenging, and blank days are not uncommon.

On a recent visit to Malham, I was shown a cased brown trout in the common room (formerly the library) of Malham Tarn House. The label in the bottom left-hand corner of the case states that the fish, weighing 4 pounds, 1 ounce, was caught on 20 September 1905 by Thomas Brayshaw Jr. The person who showed me the trout—which is actually a painted plaster cast—had no idea who the captor was, but the name sparked a distant memory in me. After some research, I have come to believe that this fish has a fascinating story to tell.

Tommy Brayshaw, the captor of this fine specimen, was a man of many talents who is more famed across the Atlantic than in his native Yorkshire. Brayshaw was born in Giggleswick, North Yorkshire, on 3 March 1886. His father, also called Thomas, was a solicitor by profession with an office in nearby Settle, a governor of the famed Giggleswick School, a keen local historian, and an angler who controlled fishing rights on the nearby River Ribble. Like generations of his family before him, the young Tommy was educated at Giggleswick, where he received a traditional public school education.1 Not surprisingly, because both his father and uncle were avid anglers, Brayshaw started fishing at the age of eight, when he was given his first fly rod. He was only allowed to fly fish, and in his first year as an angler, he failed to catch a single fish.2 However, he caught about a half dozen fish the next year, which ignited a passion that lasted the rest of his life.

At the age of eleven, Brayshaw began to tie his own flies, and by the time he was fourteen, he was corresponding with George M. Kelson about the dressing of salmon flies. Brayshaw would dress some of Kelson’s creations and send them to him for criticism. Kelson was a stickler for the use of the correct feather, and woe betide Tommy if he used a substitute!3

Much to the amusement of his elders, who thought he was wasting his time, the young Brayshaw began fishing Malham Tarn in 1900. On his first visit, he promptly caught a trout of 1 pound, 9 ounces. From then on, he was a confirmed Malham Tarn fisherman and availed himself of every opportunity to fish its rich alkaline waters. In a letter written to P. F. Holmes, then director of Malham Tarn Field Centre, in February 1950,4 we learn that Brayshaw liked to be on the water by dawn, often leaving his home in Giggleswick before midnight to make the arduous journey uphill to the tarn. It appears that he had an arrangement with Alfred Ward, the keeper at the time, to leave the boathouse door unlocked. On one occasion Ward forgot, and the hapless Tommy had to wade round the front of the boathouse at 4:00 a.m. to gain access to the boat. In the years up to 1919, over thirteen seasons, Brayshaw killed thirty-five trout and returned eleven that weighed less than a pound. On 27 June 1906, he fished the Ribble all day, killing nine trout on a small Devon minnow. At midnight he set off for the tarn with his uncle, caught a trout of 1 pound, 5 ounces, before 4:00 a.m., returned home for breakfast at 8:00, then went off to the Ribble again where he caught twelve trout, two grayling, and an eel.5 He was keen in those days!

It was on 20 September 1905 that Brayshaw caught the trout now on display in Tarn House. From the aforementioned letter to P. F. Holmes, we learn that the case had been wrongly labeled and that the trout was actually 4 pounds, 10 ounces, not 4 pounds, 1 ounce, as indicated—an easy mistake to make. The trout in the case is a painted plaster cast (with a crack in its tail, likely a result of poor handling); the actual fish was given to the Hancock Museum in Newcastle, where it was preserved in formalin.6 Unfortunately, in spite of extensive inquiries, I have been unable to ascertain whether the fish still forms part of the museum’s collection. Although the 4-pound, 10-ounce trout was clearly a personal best for Brayshaw, it failed to match up to his uncle’s best Malham trout, a fine specimen of 5 pounds, 13 ounces, which was also set up in a glass case, the whereabouts of which is unknown.7

In 1904, at age eighteen, Brayshaw began a six-year apprenticeship in draughtsmanship with Palmer’s Shipbuilding and Iron Company at Jarrow-on-Tyne. From then on, his fishing at Malham Tarn was restricted to holidays (he caught his specimen trout in 1905 at age nineteen). Brayshaw soon became a member of the Northumbrian Anglers’ Federation, and Saturday afternoons saw him on the banks of the Coquet, famed for its trout and salmon.8 In 1907, he contributed an article on angling titled “Stray Casts” to the company’s journal, the Palmer Record, complete with photographs and a tailpiece drawing of a salmon.9

After completing his apprenticeship in 1910, Brayshaw moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, where he was employed by the Yorkshire Trust. It was in British Columbia that he discovered the delights of fishing for steelhead, and he regularly fished the Capilano, Seymour, and Coquihalla Rivers. He also fished for chinook salmon on the famed Campbell River on Vancouver Island. Brayshaw’s time in Canada was cut short by the outbreak of World War I. He returned to England in 1914 and joined the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment but was wounded the following year in France. His talents, however, were not wasted, and he was put in charge of the Tees Garrison revolver school, where he wrote a training manual illustrated with his own line drawings. But before leaving for the front in France, Brayshaw met a young woman who was serving with the Red Cross in a military hospital in Wakefield. Her name was Edith Rebecca “Becky” Sugden. They married on 5 July 1916.10

At the beginning of 1919, Brayshaw was discharged from the army, having attained the rank of captain. The following year, Tommy and Becky returned to British Columbia, where they bought a house and small orchard in Vernon, and where Brayshaw took a teaching post at the Vernon Preparatory School.11

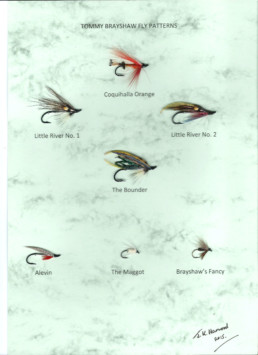

The years between the two world wars proved a fruitful time for Brayshaw. During the long holidays and on weekends, he went fishing. One of his favorite venues was Knouff Lake, famed for its hard-fighting Kamloops trout, where he took fish up to 17 pounds on floating sedge imitations.12 He also fished the Adams and Little Rivers, for which he developed a series of flies, the Little River Nos. 1 and 2,13 and the Bounder14 (see illustration). It was Brayshaw’s custom to carry with him a portable fly-tying kit, and the Alevin fly was devised in April 1939 in imitation of the fry in the Adams River, which were still displaying their yolk sacs. The throat hackle, originally tied with Indian Crow feather, represented the sac. The fly—originally called the Yolk Sac but later changed to the Alevin—proved deadly for the Adams River rainbow trout.15

Brayshaw’s carving of J.H. Muller’s 1932 Jewell Lake trout, which sold for a record price at auction in 2005. Photo by kind permission of Neil Freeman of Angling Auctions, London.

Brayshaw is perhaps best remembered for his hand-carved and painted models of fish. Some of his best specimens are highly sought after by collectors and can command thousands of dollars. He first started making fish models in 1927, when the Reverend Austin C. Mackie (the founder and headmaster of Vernon Preparatory School where Brayshaw taught) brought him an 8-pound trout from Knouff Lake and asked him to cut an outline of it out of plywood. Brayshaw did as instructed but was unhappy with the cutout’s sharp edges. He rounded the edges, painted the cutout, and presented it to the reverend on Christmas day. The Reverend Mackie was very pleased with the model, and Brayshaw was encouraged to continue carving fish.16

By the mid-1930s, Brayshaw’s carvings of trophy fish had gained international recognition. In June 1932, a small party of English anglers came out to the Kamloops area of British Columbia to fish for rainbow trout, and they commissioned Brayshaw to make carvings of some of the fish they caught. In 2005, one of these carvings, an 18-pound trout caught by J. H. Muller in Jewell Lake, came up for auction in London, where it sold for a record price of $33,000 at Neil Freeman’s Angling Auctions.17

During his lifetime, Brayshaw carved around fifty-five fish trophies. He was meticulous in his attention to detail, carving out the individual scales of the fish and even grinding up mother-of-pearl to mix with his paint to give the fish an iridescent sheen.18

The autumn of 1933 proved memorable for Brayshaw. While fishing for Chinook salmon on the Campbell River, he met another ex-pat, angler and author Roderick Haig-Brown, who originally hailed from Lancing in Sussex. The two became lifelong friends.19 Toward the end of World War II (during which Brayshaw served as a training officer with the Rocky Mountain Rangers and later as a recruiting officer, retiring with the rank of major), Haig-Brown asked Brayshaw to illustrate a new edition of his classic work, The Western Angler, which was published in 1947. This launched Brayshaw on a new career path: that of illustrator and artist.

Not only was Brayshaw a talented fish carver, fly dresser, and illustrator, he also built his own split-cane rods. He was given lessons in rod building by Letcher Lambuth, the noted Seattle rod maker, following a chance meeting with him in September 1944. The two became firm friends, and Brayshaw built a number of cane rods from 6 to 14 feet in length, most of which were eventually given away to his friends, although one is on display at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria.20 Brayshaw continued to make rods until 1963, when he was forced through ill health to retire to an apartment in Vancouver.

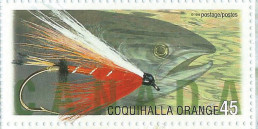

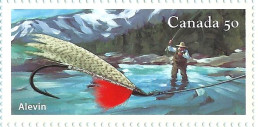

Tommy Brayshaw passed away on 10 October 1967 at age eighty-one. In his will, he donated his extensive collection of angling books, personal letters, and fishing diaries to the University of British Columbia. Unfortunately, he did not live long enough to see two of the fly patterns he created immortalized on stamps issued by Canada Post. In 1998, Brayshaw’s Coquihalla Orange Fly, which he devised for steelhead fishing in the Coquihalla River during the 1930s,21 was chosen as one of six flies in a commemorative fishing-flies stamp set. Seven years later, in 2005, another of Brayshaw’s creations, the Alevin Fly, was one of four flies in a set of stamps featuring fishing flies. Tommy Brayshaw clearly came a long way from his early days on Malham Tarn. His fish models and illustrations can now be found in a number of venerable institutions and are an enduring testament to his creative genius.

*This article first appeared in slightly different form in the Winter 2016 issue of Waterlog.

Endnotes

1. Stanley Read, Tommy Brayshaw: The Ardent Angler-Artist (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1977), 31.

2. Ibid., 32.

3. Ibid., 21.

4. Thomas Brayshaw to P. F. Holmes, 26 February 1950, University of British Columbia Library, Vancouver, Rare Books and Special Collections, Thomas Brayshaw fonds 1907–1967, folder 5–10.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Read, Tommy Brayshaw, 32.

9. Thomas Brayshaw, “Stray Casts,” The Palmer Record (December 1907), 191–96.

10. Read, Tommy Brayshaw, 34.

11. Ibid., 33–34.

12. Jack W. Berryman, Fly-Fishing Pioneers and Legends of the Northwest (Seattle: Northwest Fly Fishing LLC, 2006), 22.

13. Arthur James Lingren, Fly Patterns of British Columbia (Portland, Ore.: Frank Amato Publications, Inc., 1996), 24.

14. Ibid., 17.

15. Ibid., 12.

16. Ronald S. Swanson, Fish Models, Plaques & Effigies (Far Hills, N.J.: Meadow Run Press, 2009), 167.

17. Ibid., 169.

18. Ibid., 168.

19. Berryman, Fly-Fishing Pioneers, 22.

20. Read, Tommy Brayshaw, 45–47.

21. Lingren, Fly Patterns of British Columbia, 53.