By Lance Hidy

Pete Hidy, ca. 1972. Photograph by Elaine Hidy. Hidy archive.

On 7 October 2017, Vernon S. Hidy—my father, Pete—was inducted into the Fly Fishing Hall of Fame at the Catskill Fly Fishing Center and Museum, in Livingston Manor, New York. He had been nominated several times over the years, but because relatively few remembered his many contributions to the sport, he was repeatedly passed over. This was typical for my dad, who shunned attention and refrained from self-promotion. He never compiled a fly-fishing résumé or even a list of his many publications. Consequently, none of the people who nominated him had access to the information needed to build a convincing case.

V. S. Hidy was a fly-fishing editor, writer, photographer, conservationist, and innovative fly tier. He founded the Flyfisher’s Club of Oregon, coined the word flymph, and campaigned tirelessly for James E. Leisenring’s place in the fly-fishing pantheon.

My father’s untold story was hidden in my attic, stored in cardboard cartons inherited when my mother died in 2006. Even though I had given up fly fishing in my early twenties, I, like my mother, was protective of this archive of my father’s correspondence, essays, trout flies, tying materials, reels, fishing vest, and fly rods. Eventually—as fishing writers, historians of fly tying, and collectors contacted me seeking information about Pete Hidy and his mentor, James E. Leisenring—I dutifully began to examine the archive and analyze it. To corroborate my research after an interval of forty years, I resumed fly tying and fishing myself.

Pete Hidy at his tying bench, 1940. Jim Leisenring asks Hidy to tie the winged flies to be photographed for The Art of Tying the Wet Fly. Jim can’t do the delicate work because his fingers have been roughed up doing stone masonry in Allentown, Pennsylvania, for the Works Project Administration (WPA). Letter from Jim Leisenring to Pete Hidy, 12 November 1940, Hidy archive.

I am particularly grateful to two men, Jim Slattery and Terry Lawton, who, beginning in 2010, did more than anyone else to inspire me to start organizing my father’s archive and—more importantly —to understand it. Slattery visited twice, sorting through the vintage trout flies and papers. He also allowed me to photocopy Leisenring letters and manuscripts that had once been among my father’s papers, but which he had acquired after my mother auctioned them in 1996. Through Slattery I became acquainted with the members of the International Brotherhood of the Flymph and their online Flymph Forum, of which he was a cofounder. Slattery also introduced me to Terry Lawton, the English fly-fishing writer and journalist, who was frustrated by the dearth of information about Hidy and Leisenring. Lawton and I enjoyed a lively trans-Atlantic correspondence as I probed the Pete Hidy archive and shared my discoveries. I am grateful for the accuracy and grace with which Lawton reported, in his books, on the contributions of both men.

One of Those Rare Spirits

From his first published words until the end of his life, Hidy never wavered from the idea that fly fishing was to be pursued for pleasure and that trout streams were “sanctuaries,” where, through the art of angling, one could enjoy a “contemplative conversation with nature.”1 Furthermore, he would never violate this sanctuary by ever speaking ill of any person. Hidy’s correspondents sometimes tried to engage him in criticism of mutual acquaintances, but he always deflected the discussion toward shared pleasures. Roger Bachman, who long worked with Hidy on the editorial team for the Creel, observed, “After Pete left town the Creel team fell into tense battles, which Pete had smoothed over when he was here. . . . Not only was his smiling grace the glue that made the Creel work flow, I think we all missed seeing him regularly.”2 Arnold Gingrich, angling writer and editor, and cofounder of Esquire magazine, wrote of Hidy, “He is one of those rare spirits who could, almost single-handedly, give a sport a good name.”3

In contrast to those anglers who measured their pleasure by the number and size of fish caught, Hidy offered an alternative. He called it the Fisherman’s Law, and put it on the cover of one of the last issues of the Creel (November 1978), the journal that he started in 1961 for the Flyfisher’s Club of Oregon: “Fishermen may find unexpected pleasures more enjoyable than the ones they seek.”

This was true to his nature. Even his description of childhood fishing in the flatlands of Ohio sparkles with memories of such pleasures:

I liked to explore the stream named Paint Creek that flowed through the pastures and on across the countryside to the old Hidy Cemetery, where many of our ancestors and relatives are buried. . . . I learned to fish with worms and crawfish for bass, perch, catfish, and carp, and during the hot afternoons I would see blacksnakes in the thickets where I picked blackberries; and I got acquainted with many birds up in the trees I climbed for fun and juicy cherries and mulberries. . . . When it rained, I would take a kerosene lantern, a long, one-piece bamboo pole, and a can of worms and go fishing for catfish. The sounds of the owls and big bullfrogs and falling rain made music in the night.4

One of a set of hackle identification cards made by Hidy, ca. 1973–1975. Hidy archive.

Equally revealing is the opening sentence of Hidy’s first published writing: the succinct, 237-word introduction to Reuben R. Cross’s Fur, Feathers and Steel: “As one learns fly-fishing and learns to love its beauty, artistry and lore, he comes across the name of Rube Cross” [italics mine].5

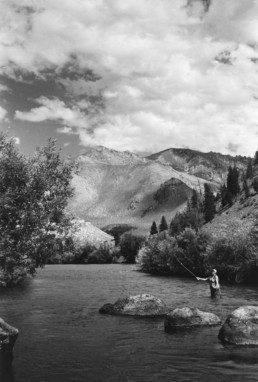

Hidy would offer his finest expression of fly fishing’s “beauty, artistry and lore” in his 1972 book of photographs and extracts from angling literature, The Pleasures of Fly Fishing. The preface stands alone among all of Hidy’s writing as a credo for his life in the sport. Toward the end, he explains how it happened that his creel was more likely to contain a camera than a trout:

The angler’s camera, like his rod, becomes an intensely personal tool. Ultimately, his collections of slides and prints are as great a source of pleasure as his tackle and flies. Not for themselves as things, certainly, but for their power to evoke the magic of the days spent on the water. . . .

For the angler, pictures are a record of our passing through a valuable and irreplaceable environment . . . the simple joys of appreciating the changing moods and beauty created by clouds, wind, sunlight, and shadows. . . .

The fly fisherman with a camera in his creel leaves his sanctuaries scrupulously unmarked . . . carrying on his contemplative conversation with nature . . . achieving a certain relationship between himself and wildness . . . within a large solitude . . . perceiving the music of the river. When he kills a fish or two for the fire, he does so in the spirit of “harvesting the crop.” With his camera, however, he harvests an inexhaustible, perpetually renewable resource of pleasure.6

This photograph by Pete Hidy is similar to one in The Pleasures of Fly Fishing, 1972, pages 86–87. The identity of the fisherman and the river are unknown, but it might be the South Fork of the Boise River near Mountain Home, Idaho. The whereabouts of the original prints reproduced in the book are also unknown. Hidy archive.

During 1933–1934, pleasure could be elusive. The Great Depression caused the Hidys, like countless other families, to become economic migrants. Hidy, his two younger brothers, parents, and grandparents were forced to leave Ohio, seeking refuge with relatives in Buckingham Valley, just north of Philadelphia. His college education cut short after only two years and, the nation in crisis, Hidy looked to see what pleasures his new Pennsylvania home could offer to a fisherman. He learned that 70 miles north, in the Pocono Mountains, was one of the finest trout streams in the East: Brodhead Creek. Never having fished for trout in Ohio, he would take a look.

Immediately Hidy fell in love with the feather fly, the affectionate term he used when remembering those early days, when he was in his early twenties. He even started fly-tying lessons. Having taken up journalism in college, he also embraced the literature of fly fishing, which some insist is the oldest and most excellent literary tradition of any sport.

Not long after immersing himself in the art of fly fishing, Hidy attracted the admiration and friendship of two of the most distinguished fly fishermen that America has ever produced: Reuben Cross (1896–1958) and James Leisenring (1878–1951). Letters from those days reveal that Hidy fished with each man and was responsible for introducing them to each other.7 Did the three ever fish together? It would have been a notable event, but the archive is silent on the subject.

What we get a sense of, though, is the kind of good faith and friendship that Hidy engendered. His love and enthusiasm for the sport always shined through, but there was also his self-effacing nature, which came perhaps from his journalistic instinct to deflect attention from himself and to shine the spotlight on others—in this case, his friends Cross and Leisenring.

Now it is time to turn the spotlight on Pete Hidy.

To read the rest of this piece, check out the Winter 2018 (Vol. 44, No. 1) issue of The American Fly Fisher.

Endnotes

- Vernon S. Hidy, The Pleasures of Fly Fishing: Photographs and Commentary on Streams, Rivers, Lakes, Anglers, Trout & Steelhead, Including a Selection of Memorable Observations from the Classic Writings of Angling Literature (New York: Winchester Press, 1972), 8.

- Roger Bachman, e-mail to author, 22 February 2011.

- Arnold Gingrich, The Fishing in Print (New York: Winchester Press, 1974), 323.

- V. S. Hidy, “The Sketch of My Life,” unpublished typescript, ca. 1979, Lance Hidy archive.

- V. S. Hidy, introduction, in Reuben R. Cross, Fur, Feathers and Steel (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1940), ix.

- Hidy, The Pleasures of Fly Fishing, 8–9.

- Letters between Pete Hidy and Jim Leisenring can be found in the personal archives of Lance Hidy and Jim Slattery.