By Robert J. Demarest

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) is considered by many to be the finest painter America has produced. He was also an accomplished fisherman whose passion for fishing was more than a recreational diversion. It was a vital and integral part of his life, his personality, and his art. Without an understanding of how important it was to him, much of his career cannot be fully appreciated. Homer’s paintings of trout, salmon, and bass fishing are more than depictions of sporting moments- they are a testament to his love of the sport itself. Throughout his life, he traveled great distances to find good fishing. Once there, if he felt inspired, he would capture the experience with his brush. His frequent visits to the Adirondacks and Canada, and his trips to Florida, were undoubtedly motivated more by his desire to fish than to paint. Fortunately for us all, he brought his paint box along with his fishing rod. Homer’s love of fishing started early. Growing up in then-rural Cambridge, Massachusetts, he had plenty of opportunities to hone his fishing skills at near- by ponds and rivers. Even when working full time, he managed to find time to fish. His first biographer, William H. Downes, tells of him rising as early as 3:00 a.m. and hiking to Fresh Pond in Cambridge (now Belmont), to go fishing. He would then catch the omnibus to Boston, making it to Bufford’s lithography shop-where he was employed as an apprentice between 1854 and 1857-in time for work at 8:00 a.m.1

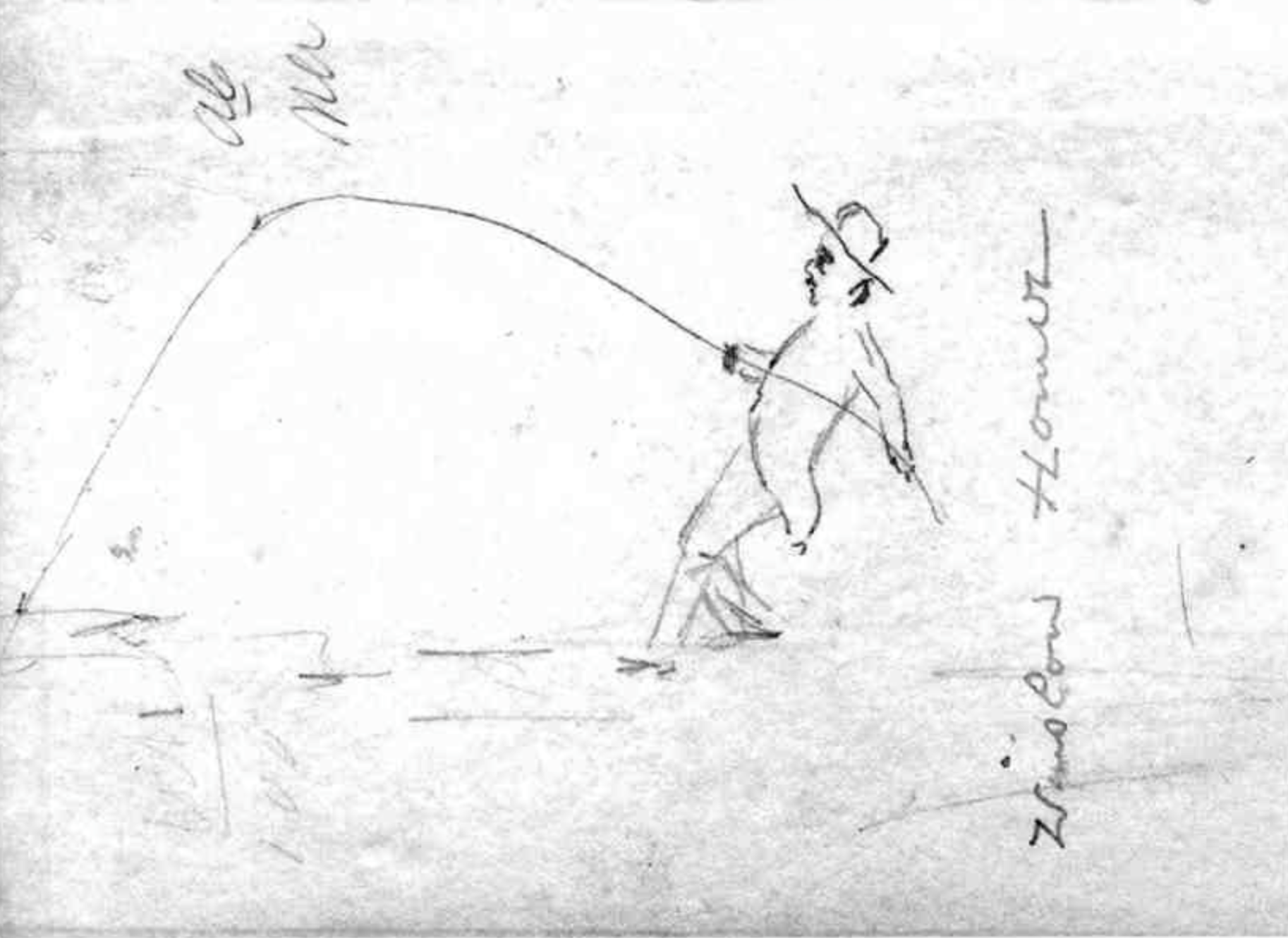

Man Fishing, by Winslow Homer. Pencil sketch on front endpaper of Homer’s copy of Boy’s Treasury of Sports, Pastimes, and Recreations (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847). This sketch is probably from Homer’s childhood and is his earliest known treatment of the sport that captivated him throughout his life. David Tatham (The American Art Journal, May 1977) dates it somewhere between 1847and 1854. Courtesy of the Strong Museum, Rochester, New York

His letters, as well as the great number of his fishing scenes, attest to this life- long interest. His knowledgeable renderings of fly fishermen as well as his beautiful evocations of trout. char. and salmon graphically show his love for the sport. Perhaps as telling is his choice of destinations for many trips throughout his life. Prouts Neck. Maine, was his home, where the winters were long, so it is easy to see how Florida, Cuba, the Bahamas, and Bermuda would beckon. But more than the balmy weather interested him. Of his eight recorded trips to Florida, he apparently only painted on three, preferring simply to fish on the other occasions. On one trip, when he did paint. he wrote a letter to his younger brother Arthur, and in it does not mention his paintings at all: “Fishing the best in America as far as I can find.”2

Interestingly, sketches, which made up the large part of the letter, showed the fish he was catching.

Summer also afforded many occasions for fishing. In addition to waters around Prouts Neck, he often fished with his older brother Charles in the Adirondacks and Quebec. Even though he carried his watercolors on his trips, it was often a question of what was more important, fishing or painting? It seems that fishing often won out.

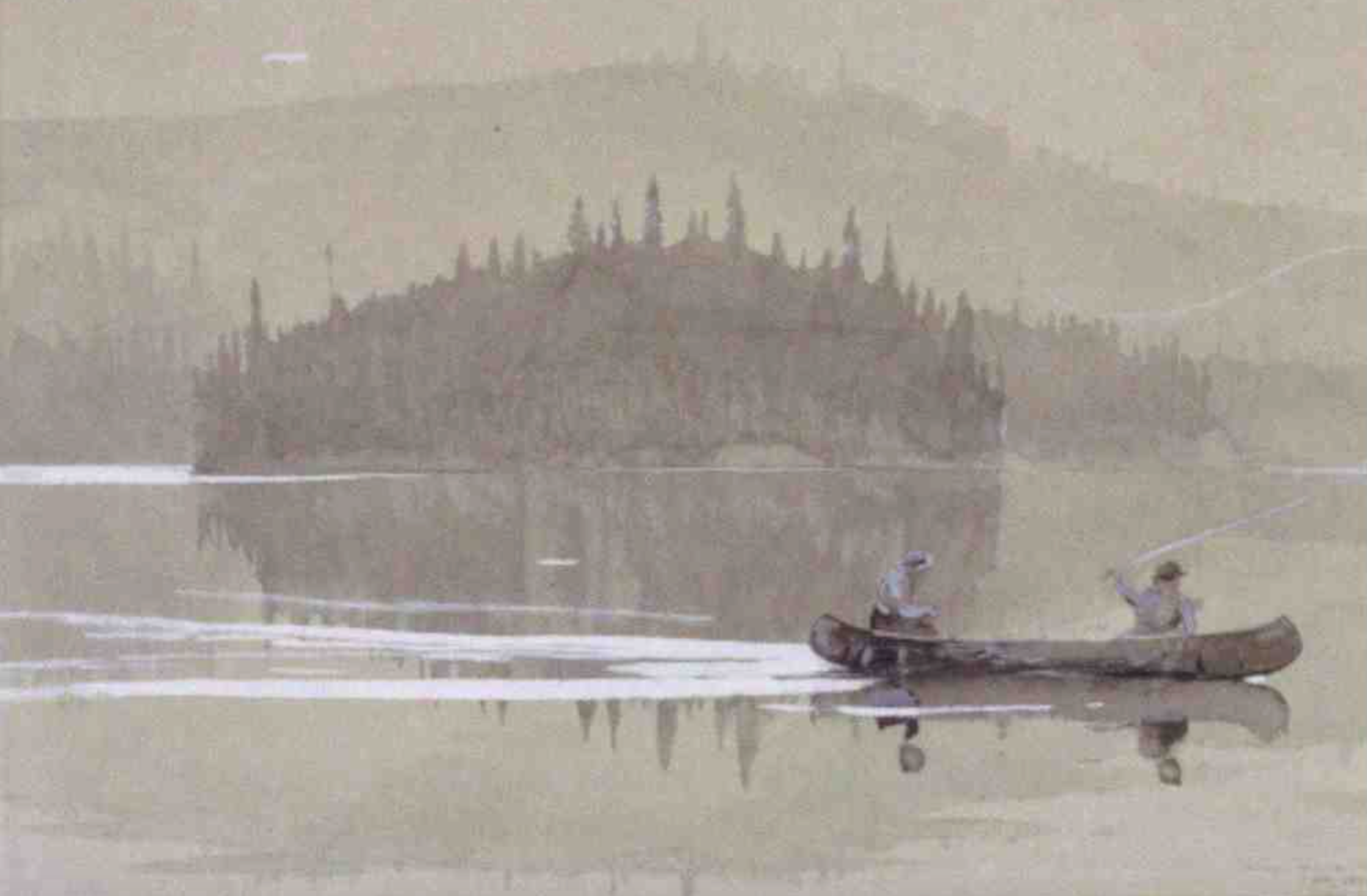

In Homer’s day, just getting to some of these places took considerable time and effort. He and Charles were members of the Tourilli Fish and Game Club in Quebec, located thirty miles west of Quebec City. Despite the long trek to the club and the lake, they liked it so much that they built a cabin and kept a boat there. Thev also went loo miles farther north, to the Sanguenay River and Lake St. John, for salmon fishing. As an artist, he took advantage of fishing with his brother to capture some of the realism of the experience on paper. Working from another boat, he wrote of “sketching on the fly”-that is, sketching his brother and guides in their boat while they were fishing and canoeing.3 The action in these scenes indicates that his subjects were not posing, perhaps so taken with the task at hand that they were unaware of. or unconcerned with. Homer’s careful scrutiny and sketching Surely this approach enhanced the natural feeling and authenticity in much of his work. In addition, his boat-level perspective, characteristic of many of Homer’s fishing scenes, brings the viewer right into the picture.

Two Men in a Canoe, 1895. Watercolor on woven paper, 13 15/16 inches by 20 1/16 inches. Courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Bequest of Charles Shipman Payson, 1988.55.12.

There is no doubt that Homer was greatly enamored of fly fishing, which is shown in Jumping Trout, The Rise, and Two Men in a Canoe. In Two Men in a Canoe, the fisherman is casting a fly to the spot where a fish is feeding. In The Rise, the telltale circles of a feeding fish are an essential element in the composition as well as the overall drama of the painting.

Jumping Trout (1889) shows a fly, which appears to be a Red Ibis, with an attached dropper fly disappearing into the water. Using droppers-additional flies tied to the same line-was a typical fly-fishing method at the time that Homer painted this picture. As many as a dozen droppers might be attached to the same line, often with different flies on each dropper. This offered the fish a veritable smorgasbord of choices. Of course, the fisherman had to contend with a possible tangle of flies on every cast. Today fly fishers occasionally use droppers, but seldom more than one at a time.

Jumping Trout, 1889. Watercolor on paper. 13 15/16 inches by 20 inches. Donelson F. Hoopes, in Winslow Homer Watercolors (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1969), says, “To the knowledgeable eye, Homer has shown the trout aiming not for the scarlet fly in thepicture, but for the second-and invisible-lure at the end of the barely visible leader” (p.74).Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum of Art,Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 41.220.

The American Museum of Fly Fishing has one of Homer’s fly rods in its collection. It is a 9½-foot, six-strip split-bamboo rod with his name on the case. These bamboo rods were the quality rods of the day. Until the mid-18oos, solid rods were used, but they were fragile and “whippy.” When the process of gluing tapered strips of bamboo together was developed sometime in the 1840s, bamboo rods quickly became the rods of choice for the ardent (and well-to-do) fisherman. Homer was surely a devotee and, although not rich, he wanted the best equipment for the sport he loved. More commonplace rods were of hickory, juniper, ash, and other supple woods, but these did not have the ideal resiliency for playing a game fish.

Unlike the bait fisherman, the fly fisherman depends on the weight of his line to take out an attached, almost weight- less fly. Many different factors contribute to the success (or failure) of the fly fisherman: presentation of the fly so as not to disturb and frighten the fish; selection of a fly pattern that will attract the fish; and considerations of the current, drift, and retrieve. Wet, submersible flies were probably used exclusively during the years when Homer fished. The flies were tied with gaudy feathers from colorful birds such as the ibis, peacock, and macaw. Today many of these birds are endangered and protected by law, so fly tyers use dyed substitutes for their feathers. The Red Ibis or flies of similar color can be identified in several of Homer’s fishing pictures. Designed as an attractor fly for brook trout, the Red Ibis is really too large for today’s smaller, scarcer fish. Given Homer’s penchant for including a splash of vermilion in his paintings, the Red Ibis was an easy choice for him. Today both wet and dry-fly fishing methods coexist, with most fishermen carrying both types of flies in their fly boxes

However, Homer was not exclusively a fly fisherman. Some authors have tried to imply that it was his main interest, going so far as to compare the art of fly fishing with the art of painting. Such a comparison may be tempting, as both fly fishing and painting can be a lifelong struggle in the pursuit of excellence. But that is a relatively modern perspective. If we go back far enough, we find that fly fishermen were looked upon as inferior to bait fishermen.4

The Rise, 1900. Watercolor over graphite, 13¾ inches by 20¾ inches. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of Ruth K. Henschel in memory or her husband, CharlesR. Henschel.

In the Homer literature, records of other types of fishing are numerous. John Beatty, a close friend and admirer of his work, recalls fishing with Homer at Prout’s Neck. “Homer found one of his chief pleasures in fishing, and we made many trips on the sea in a power-boat for this purpose.”5 Fishing from the rocks was even more convenient, and he was often seen doing just that. Several photographs of him fishing, and with his catch, attest to his interest and success. Philip Beam recounts that Winslow and his brothers “spent every possible spare minute fishing at Prout’s, in the Adirondacks, Quebec Province, Florida, and the West Indies.”6 Boyer Gonzales, his young friend and fellow artist from Galveston, Texas, writes, “He painted when things were just right, but he fished always, and a more successful fisherman, I have yet to meet. The sea black bass, tautog, that lurked in the shadows of the rocks as the Atlantic surged over them was his game. When the tide was out many delightful walks did we take, in search of the little crabs, that he used for bait.”7

Homer wrote of fishing in the Homasassa River in Florida for channel bass, black bass, sheepshead, and “Cavalle” (the latter, based upon his sketch, is probably the Jack Crevalle). This suggests that he used a variety of fishing methods, including the casting of a lure and the use of bait. Casting or trolling a metal spoon was common in the 1800s.

In the register at the North Woods Club in the Adirondacks, Homer sketched the hook with which he caught a 6¼-pound pike.8 It shows a type of hook that would be used for holding a baited minnow. In Beaver Pond, where Homer caught that pike, bait fishing will still tempt huge pike out of the weed beds. A stout rod instead of a lighter, more fragile bamboo flv rod is recommended for these fierce fighters. Bass, too, will grab a hooked, wounded minnow and are best landed on a heavier rod. I had the pleasure of catching a 6¼-pound pike in Beaver Pond myself one recent August evening. This is as close to Homer as I will ever get!

As a member of the North Woods Club, Homer had a choice of lakes and fishing methods. Their seven lakes have different characteristics, with each being conducive to a different kind of fishing; Some ponds were stocked with trout and others with bass. Some were designated for fly fishing only and others for whatever method the fisherman chose. These designations and varied stockings were not arbitrary decisions. “By this time (1906) the fish committee had pretty well determined which fish prospered best in each pond.”9 This statement reflected the nature of each lake and took into consideration such things as the depth of the lake, weed density, water temperature, and fish survival rates.

Many of Homer’s paintings of fishermen on the North Woods Club lakes indicate trolling was being used. Trolling for trout is still practiced there and is the method of choice in some of the lakes. Bait, kept in a fish trap, was also available to members for many years.

It seems fair to conclude that Homer enjoyed all types of fishing and that he would use the recommended or optimum fishing method at each location. Most fishermen would agree that natural surroundings, companionship, the chase, and quiet moments for contemplation all combine to make any day on the water a good day. In these respects, Homer was a typical fisherman. We can be grateful that he also chose, on occasion, to capture these attractions in paint.

ENDNOTES

- William Howe Downes, The Life and Works of Winslow Homer (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 28.

- Correspondence from Winslow Homer to his younger brother, Arthur, in Galveston, Texas, 1904. Homer Collection, Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

- Letter in the Gonzales Family Collection, Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas. This is from a Scarboro [sic], Maine, letter to Boyer Gonzales from Winslow Homer dated 14 December 1899.

- J. Lawrence Poole. Isaak Walton: The Complete Angler and his Turbulent Times (New York: Stinehour Press, 1976), 34.

- John W. Beatty. “Recollections of an Intimate Friendship.” In Lloyd Goodrich, Winslow Homer (New York: Macmdlan Company, 1944), 212.

- Philip C. Beam. Winslow Homer at Prout’s Neck (Boston:Little, Brown and Co., 1966), 42.

- Document (MSS #89-0016 1-14), “Some Reminiscences of Winslow Homer,” written in Boyer Gonzales’s own hand. Gonzales Family Collection, Rosenberg Library, Galveston,Texas.

- This sketch can be seen in the collection of the Adirondack Lakes Center for the Arts, Blue Mountain Lake, New York.

- Leila Fosburgh Wilson, The North Woods Club 1886-1986 (NewYork:privateprinting,1986), 17.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2002 (Vol. 28, No. 2) issue of the American Fly Fisher.

1 Comment

Add comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A moving summary of a life’s work of sporting art by a fabulous painter. The quote: “Trout only live in beautiful places” is the essence of Homer’s personal expression, in splashes and dabs of paint on paper and canvass, of his love of the outdoors. Thanks for featuring articles such as this one that elevate the sport of trout fishing to a spiritual level that reminds us of our universal connection with all of Earth’s creatures.