BY GERALD KARASKA

Frank Benson (1862–1951) is regarded as one of America’s premier artists. His reputation was established at the turn of the twentieth century by his numerous awards and by high demand for his impressionist paintings. Benson’s popularity was further secured when he began to produce wildfowling art and a prodigious number of intaglio prints.

Over the years, only a small part of his reputation could be attributed to his angling art. From the early 1920s to his death in 1951, Benson produced more than two hundred oils, watercolors, and etchings of salmon and trout fishing. Even today, very little acclaim is given to this facet of his sporting art. Yet his angling art is a clear reflection of the special character and personality of the artist and of his enormous skills as a sportsman.

Apparent first and foremost in his art is Benson’s love of nature, which was complemented by his avid participation in physical sports.1 Early in life he boxed, played tennis, sailed, and pursued many activities that required physical dexterity and agility. He was a big man in every way—hale, hearty, and strong—and he excelled at all the sports he tried. Throughout his life his favorite pursuits were hunting and fishing. No doubt these were encouraged by the proximity of the marshes and streams close to his home in Salem, on the northern coast of Massachusetts, where he lived his entire life.

Many who so avidly admire Benson’s artistry also strive to understand the inherent content and style of the beauty he created. The innate sensuousness of his work, his awareness of the moods and rhythms of nature, and his ability to capture the mysteries of changing light reflect his personal experiences both as a participant in and an observer of nature.

BeautyAnd Style

In his sporting life, as in his art, Benson’s intensity and dedication to completing a task are evident. Many references in the literature attest to numerous episodes when, luck aside, he downed the most ducks, caught the most and the biggest fish, and spent the most time on the water. This was not, in any sense, a competition with his companions. Benson simply possessed the ability to concentrate intensely on those things he loved to do—in sport as well as in art.

Another hallmark in all of Benson’s sporting activities was his congeniality. He seemed to enjoy his outdoor activities most when he was in the company of others. His most frequent companions were members of his family. Indeed, his family was the cornerstone of his life. They joined him in everyday activities and in all manner of outdoor adventures, and they were often with him on his fishing trips. His only son, George, was his most frequent companion, and his wife, Eleanor, was with him when he fished for trout in Wareham, Massachusetts. Although his daughters often joined him for archery, sailing, and lawn sports, they only occasionally accompanied their father on his fishing expeditions.

During his twenty-four years as a teacher at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Benson enjoyed friendly relationships with many students. He formed close bonds with fellow artists who belonged to such formal art associations as the Guild of Boston Artists, the Society of American Artists, and The Ten, with whom he exhibited paintings. Many of the collectors of Benson’s art also became close friends and lifelong fishing partners.

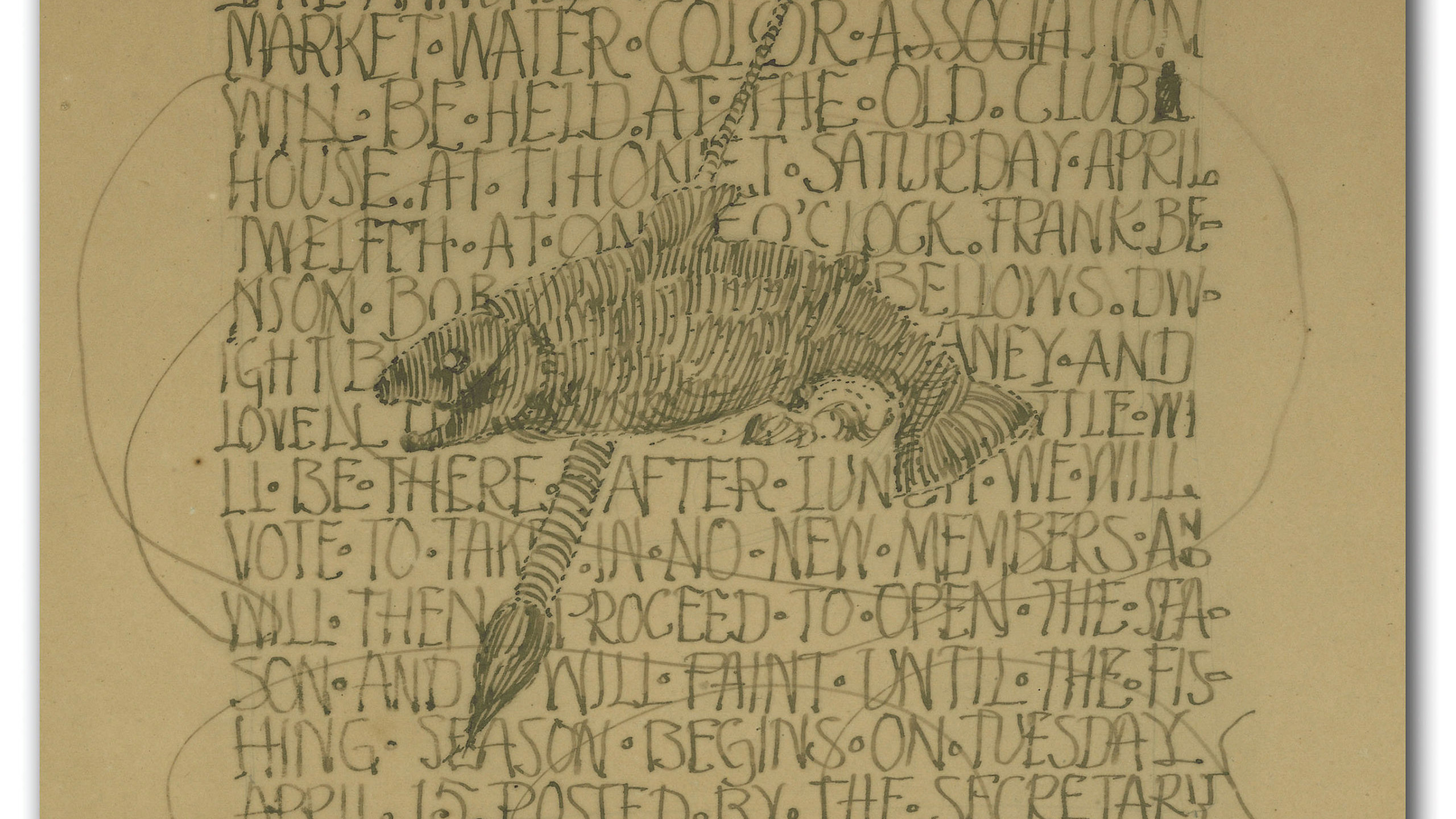

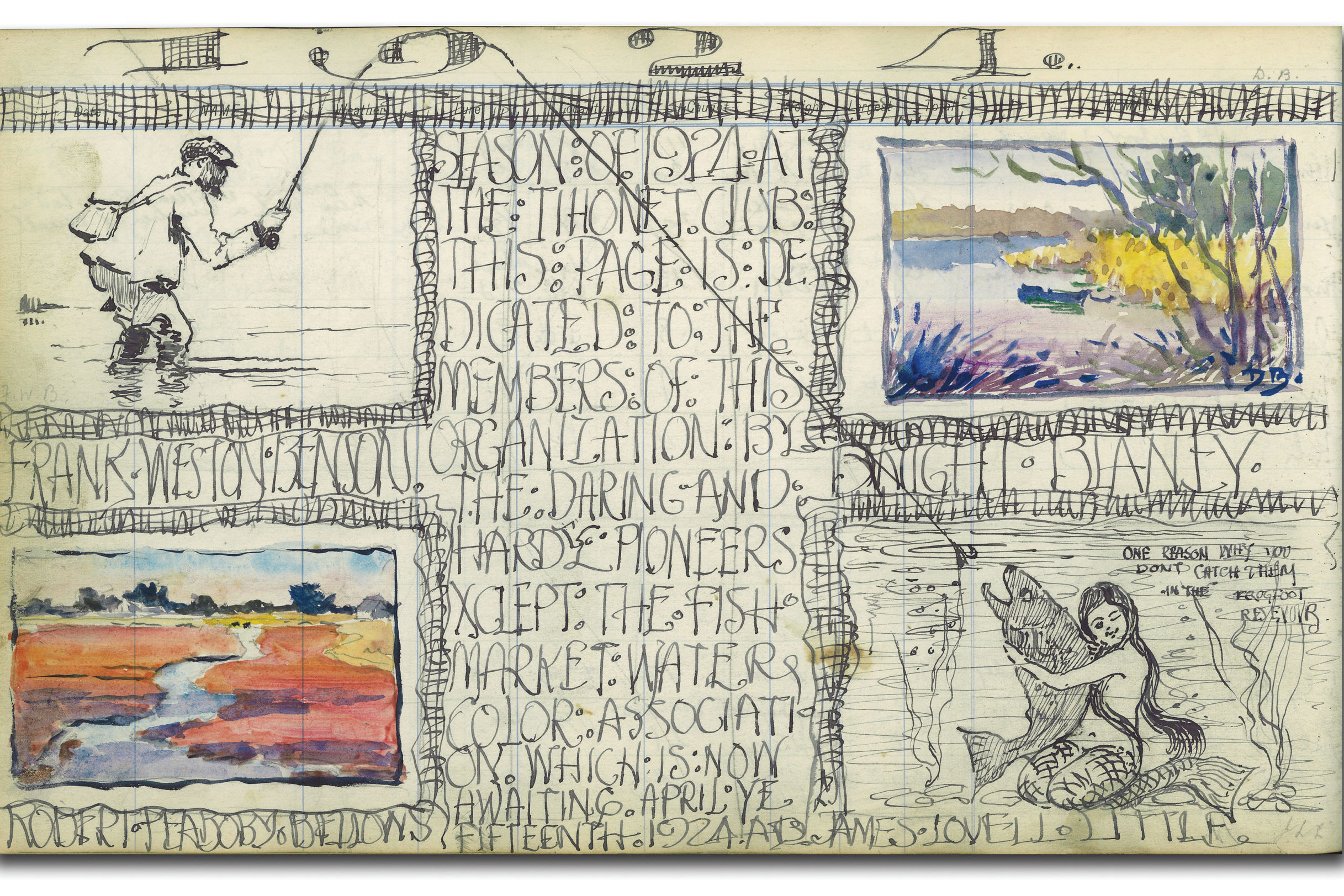

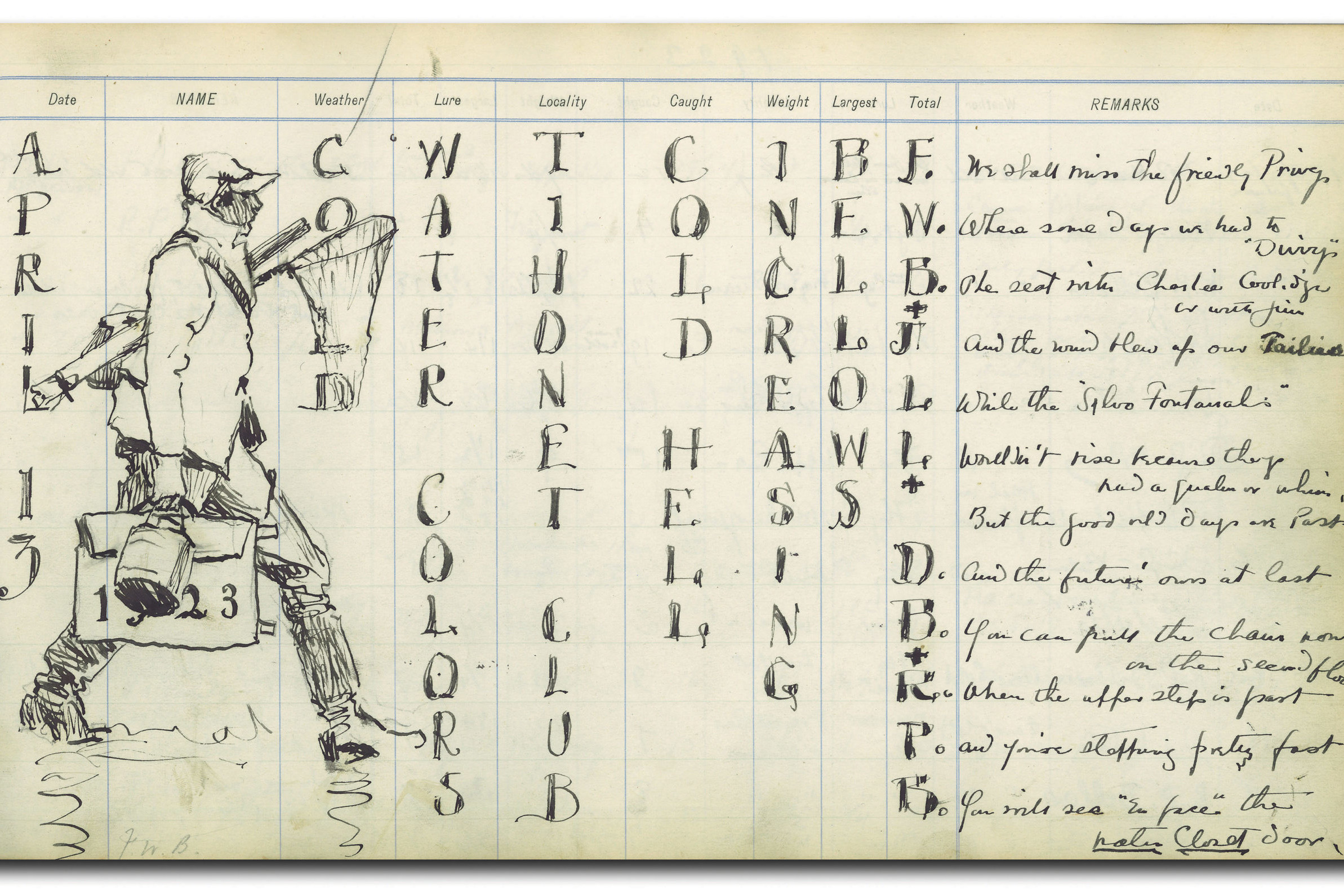

Benson frequently joined with his friends to create informal clubs or associations. For example, at the Tihonet Fishing Club, Benson and his artist friends formed the Fish Market Water Color Association and the Fish Market Water Color and Benevolent Association; at his duck-hunting cottage in Eastham on Cape Cod, he established a muskrat hunting club, the Eastham Fur Company; on a trip to the Caribbean, the Dude Club comprised his travel companions; and, at his summer home on North Haven Island, he invented a game called Fat Man’s Baseball, in which the players tied two pillows around their waists as they played. Figure 1 is a sketch by Benson that nicely describes one club:

The annual meeting of the Fish Market Water Color Association will be held at the old club house at Tihonet, Saturday, April twelfth at one o’clock. Frank Benson, Bob Bellows, Dwight Blaney, and Lovell Little will be there after lunch. We will vote to take in no new members and will then proceed to open the season and will paint until the fishing season begins on Tuesday April 15. – Posted by the Secretary.

Such camaraderie is not unusual among anglers, but the strength of these bonds for Benson was exceptional. This may seem to contradict the notion that angling is considered a solitary sport, requiring great concentration. Few men were as dedicated to the act of fishing as Benson. But the one does not exclude the other; while he greatly enjoyed the companionship of other fishermen, once on the stream or in the canoe, he shed that gregariousness and focused on catching fish.

A Long AndRewarding Artistic Life

Frank Benson experienced a long and rewarding artistic life. He first worked in portraiture, winning many prizes, the first in 1891. Subsequently, he won awards and recognition almost every year. He began exhibiting landscapes as early as 1895. For twenty years, through the turn of the century, Benson focused on sunlit plein-air paintings of his children running through meadows, sailing, and exploring the beaches of their summer home in Wooster Cove, Maine. But approaching the height of this work, the artist felt the need to explore new media and motifs.

It is worthy of note that Benson did not begin to work in watercolors until 1921 when on a salmon fishing trip to Canada. Following his son George’s advice, he took along the necessary equipment. Thus began nearly three decades of remarkable accomplishments in this genre of angling art.

Benson’s angling art differed significantly from others in that many of his paintings did not include a fisherman. When an angler was present, the image was small. Benson was in fact more likely to paint those who worked on the river as a guide, cook, or porter. Another common motif was simply a canoe or two, clear symbols of an angling scene.

Benson’s angling art is prodigious. Research has identified 110 paintings and twenty-six etchings that clearly refer to salmon riverscapes (twenty additional images could be classified as related riverscapes). There are thirteen paintings and eight etchings that depict trout streamscapes (he did twenty-nine additional paintings as related streamscapes).

Cataloguing Frank Benson’s paintings is a difficult task. In his lifetime he produced more than two thousand oils and watercolors. However, he did not keep a record of his work, nor did he identify the purchasers (largely because practically all were sold by several art dealers). Often a title, assigned by the dealer, was the only reference (sometimes a different dealer assigned another title). It also was his habit to give his paintings to friends, many of whom were fishing or hunting pals. Some of his closest friends compiled large numbers of his works.

Riverscapes, Streamscapes, and Following the Light:

The landscape genre in art obviously has a very long history, but the terms riverscape and streamscape more clearly describe Benson’s angling images. Most importantly, although the terms refer to the waters where salmon and trout are found, they accentuate Benson’s artistic insights, which focus on the play of light on sky and water. Benson urged his daughter Eleanor not to get carried away by the charm of things but to arrange them so that the light was beautiful. “Don’t paint anything but the effect of light. . . . Don’t paint things . . . at all times observe minutely the delicate variation of value between one thing and another or between light and shadow. Follow the light.”2

Benson’s angling art was distinctive in another way. His scenes did not depict real anglers facing real angling situations, nor angling action, nor the thrill of the sport (the contest or drama between man and fish). He rarely painted a fish as a trophy; in fact, one rarely sees a fish in the scene (and this was the art of a man who excelled at catching fish!). The lack of fishermen and quarry seem surprising indeed.

Water is always a presence in Benson’s angling art. It is obvious, of course, that there should be water where there is fishing, but it is the reflective surface of water that allowed Benson to paint the delicate and distinctive variations of light and shadow. That surface subtlety, especially quiet pools and rapids, becomes a counterpoint with the sky to provide the distinguishing values in his paintings. His impressionism eliminated details and allowed him to paint angling places as a synergism of light, shadow, and color. He avoided strong lines and downplayed accuracy of the human figure so as to create a personal response to what he felt about nature.

For Benson, catching fish was important for being outdoors, but his art expressed other things. For example, he frequently included guides in his paintings. Benson marveled at the skill of the guide poling a canoe laden with gear and fishermen, especially upstream through heavy currents and numerous boulders. He knew that these guides spent all of their lives in the wilderness carefully observing nature, and he felt a strong bond with them. Benson’s guides did not often comment on their surroundings, but he was aware that their senses were keenly tuned to the subtleties of nature, and his paintings reveal this understanding.

Early Trout-Stream Fishing:

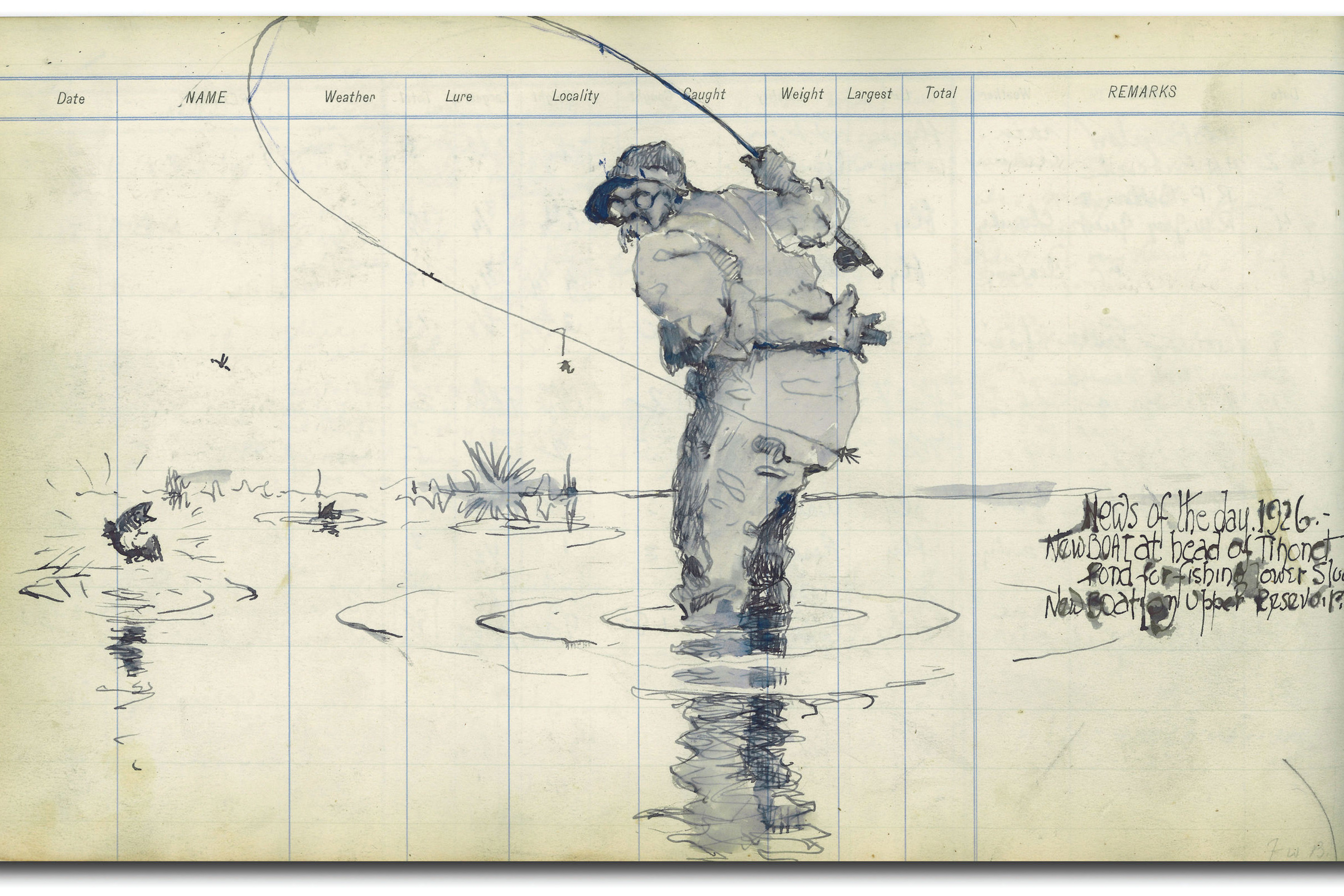

Trout fishing was clearly one of Frank Benson’s passions. It allowed him to experience nature at an intimate level, and it became one subject of his art. As a boy and young man, he avidly fished the streams near his Salem home, but he also found the streams of Cape Cod attractive. Figure 2 is an early painting by Benson, presumably of a small coastal stream.

Extensive diaries dating from 1888 (when he was twenty-six years old) to 1909 describe Benson’s numerous local fishing trips.3 The diary notes reveal routines he established and followed throughout his angling life: fishing with family and friends, and regularly fishing the same streams.

His most frequent companions were his brothers-in-law Harry Richardson and Maurice Richardson. Other partners were artists such as Philip Little, Willard Metcalf, Abbott Thayer, Alexander Pope, Bela Pratt, and Aiden Southard, but also included close friends John C. Phillips, Arthur Cabot, and Gus Hemenway. Benson noted in his fishing diary that on 26 April 1903, his son George (then twelve years old) became a regular fishing companion.

Benson’s early catches were sporadic. Often he caught only a few small fish but sometimes landed a couple of large trout. In an astonishing entry on 15 September 1890 (while fishing with Thayer, Southard, and Peale, he reported: “a hundred in all the largest [his] was one-quarter pound. Thayer got one of just one pound and Southard a big one of nearly two pounds. Peale also got one of one pound. . . . The trout were of a gold bronze color, very dark—the handsomest dark trout I ever saw and brilliantly marked.”

The Old and Dear Tihonet Club:

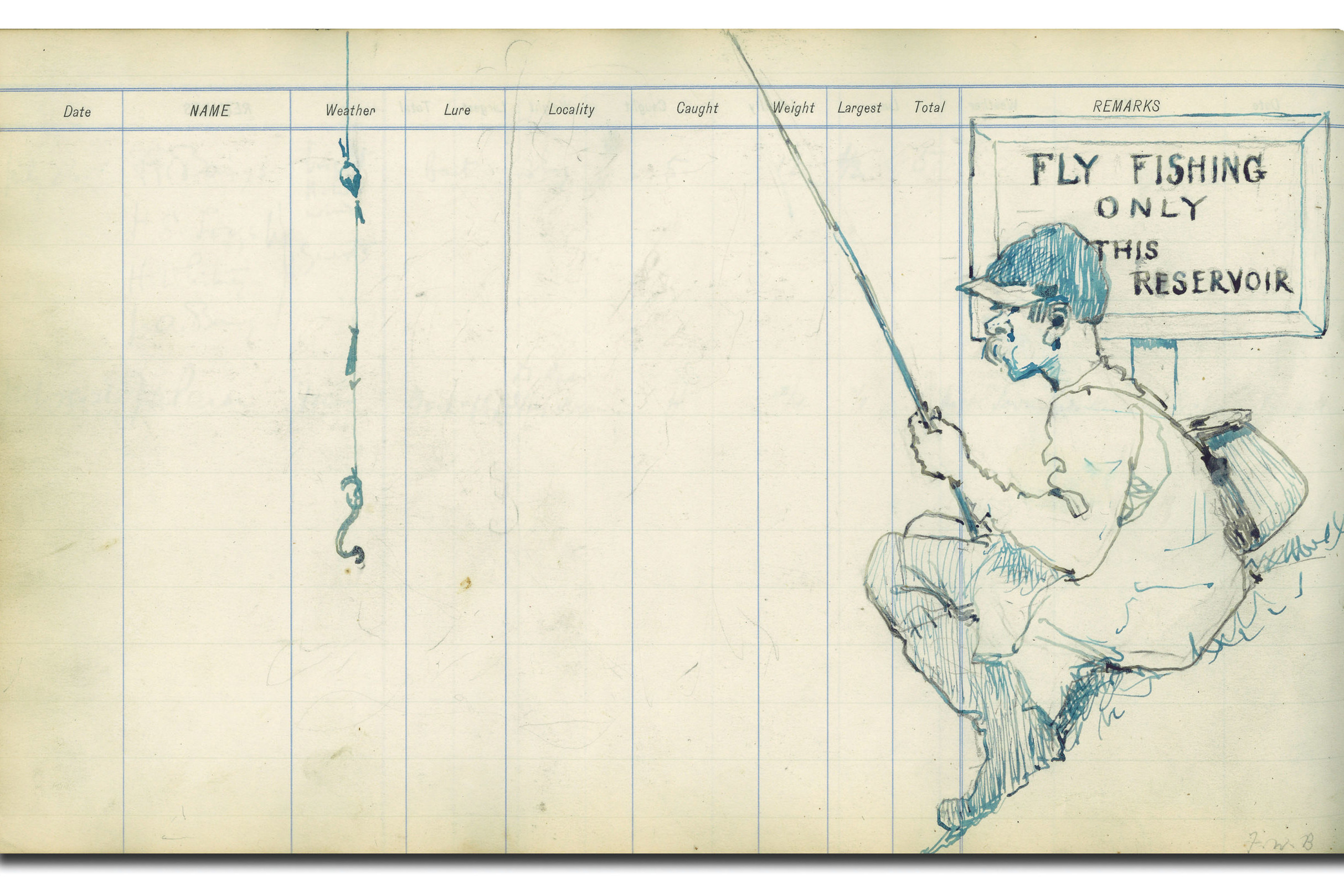

Among Benson’s favorite fishing waters for trout were those of the Tihonet Club in Wareham, Massachusetts, less than a mile from the Cape Cod Canal. The club was established in August 1891. The watershed comprised small, cold, spring-fed streams flowing from a nearby forest (now the Myles Standish State Forest). The flow of water was controlled by numerous reservoirs that regulated the levels in bogs so that cranberry cultivation could be effectively managed. Fishing was done from canoes on the reservoirs and drainage channels, as well as by wading. Figure 3 is a lithograph bookplate by Benson for the Tihonet Club.

Benson’s first entry in the club’s logs was on 14 May 1899, when, as a guest of his brother-in-law Dr. Maurice Richardson, the two caught thirty trout weighing a total of 71⁄2 pounds.4 Richardson nominated Benson for membership in 1899, and Benson began fishing as a member on 7 April 1901.

Until later in life, Benson always fished in the company of his friends, who included family, artists, and collectors. The logs also reveal that Benson fully enjoyed the club as a family setting. On numerous occasions, Benson and Richardson had supper at the clubhouse with their wives, who were sisters. An invitation to supper at the clubhouse was highly prized because Mrs. Clarence (Bessie) Besse, the club’s cook, made a delicious clam chowder.

Catching trout was clearly a goal for Benson, and his log entries reveal his prodigious success. For example, on 7 April 1906, he and son George caught eighteen trout weighing a total of 8 pounds; in three days in 1907, Benson with Bela Pratt and Maurice Richardson caught seventy-seven trout; in 1909, in eight days of fishing, Benson with his wife and son caught 155 trout weighing 60 pounds, with the largest being 3 pounds, 6 ounces (this constituted an average of 19.4 trout per day, whereas other men fished seventy-five man-days and caught 667 trout, an average of 8.9 per day).

This record of Benson’s catches becomes more amazing when one considers that the “law” of the Benson household was that everything caught or shot (except crows and gulls) must be eaten. Some explanation in defense of this lack of catch-and-release must be given: returning fish to be caught another day was not a common ethic in the early twentieth century and, most importantly, the club members paid to have trout stocked each year.

During his last years at the Tihonet Club, Benson fished less frequently. In 1939, at age seventy-seven, the logbook noted that he fished only three days (April 26 and 27, and May 19), keeping twenty-one fish and returning twenty-one. He noted on April 27: “Damn cold but it didn’t quite snow.”

Deeply Personal Art:

The rivers and streams with their rapids and boulders—together with mountains, shorelines, and forests, and especially the ever-changing light of the sky and shadows on the water—were Frank Benson’s primary subjects. He was absorbed by the places that represented the nature he loved.

How can Benson’s angling art best be characterized? He praised rivers and streams. He honored the men who lived on the water. He revered the experience of being outdoors in the nature he loved. It was a deeply personal art that revealed the places he was happiest, places where his art could be best expressed.

endnotes

1. The information on Frank Benson’s life described here is more fully elaborated in two books by Faith Andrews Bedford: Frank W. Benson: American Impressionist (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1994) and The Sporting Art of Frank W. Benson (Boston: David R. Godine, 2000).

2. Frank Benson to his daughter, Eleanor Benson Lawson. After she took up painting in 1929, she jotted down her father’s criticisms and advice in a notebook, later turning these notes into a typewritten manuscript (Family Collection and Benson Papers, Peabody Essex Museum). Quoted in Faith Andrews Bedford, The Sporting Art of Frank W. Benson, 39.

3. Frank W. Benson fishing diaries, 1888–1909, Peabody Essex Museum, Phillips Library, Salem, Massachusetts.

4. The following information was taken from the Tihonet Club annual logbooks, which recorded the daily catch of each member and guest. The logs, along with art, maps, and books, were donated to the American Museum of Fly Fishing in 2006. Special thanks to Rip Cunningham for arranging the donation.

1 Comment

Add comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] art merit serious attention, but prewar salmon-fishing scenes by 20th-century impressionist Frank Benson certainly do; likewise the fine watercolors of landscape artist Ogden Pleissner, who was at his […]