By Jay Hupp

Two days before Christmas in 1881, a young man entered one of the most prestigious fishing tackle shops in America and walked out with one of the finest fly rods available. This is the story of that rod’s purchase and its subsequent trek through three generations of use.

The young man was John E. Calhoun, student at Yale, who had one younger brother, Henry, and no surviving parents. His mother’s death in 1876 left both boys with a considerable inheritance, so John could afford the best fishing gear to be had.

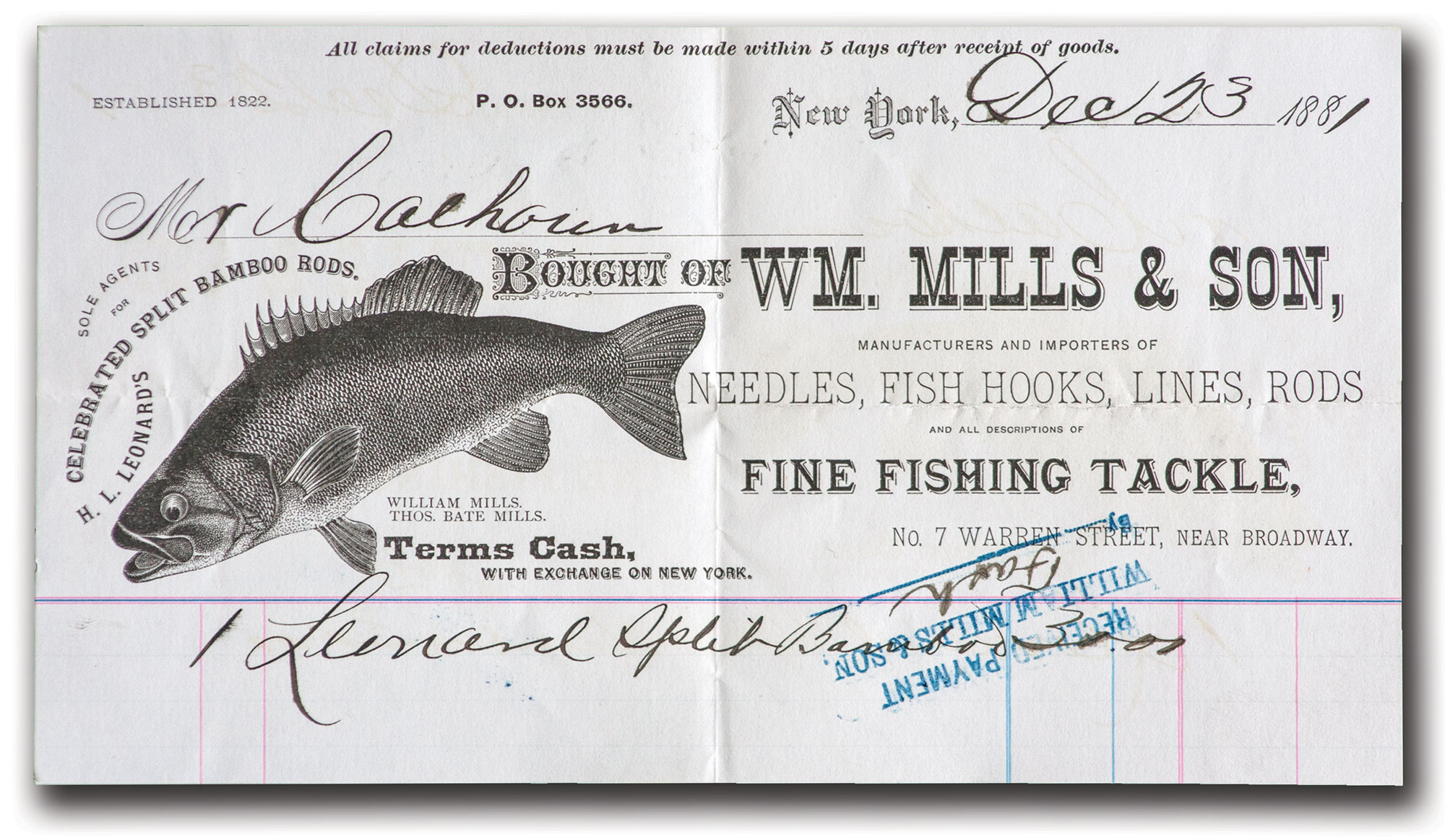

When he entered the shop of Wm. Mills & Son at No. 7 Warren Street in New York City that December day, the sales room was filled with a dazzling array of fishing equipment. The display was mostly old technology, essentially unchanged since the fishing sticks available to Izaak Walton before he wrote the original version of his Compleat Angler in 1654. Those rods were made from solid woods, such as greenheart, lancewood, snakewood, hickory, ash, and hornbeam. For the most part, they were round in shape and smooth in appearance. John could have bought a rod made of ash for $4 that day, but for some reason, he was attracted to the newer technology in the odd-looking fishing instrument made by Hiram Lewis Leonard.

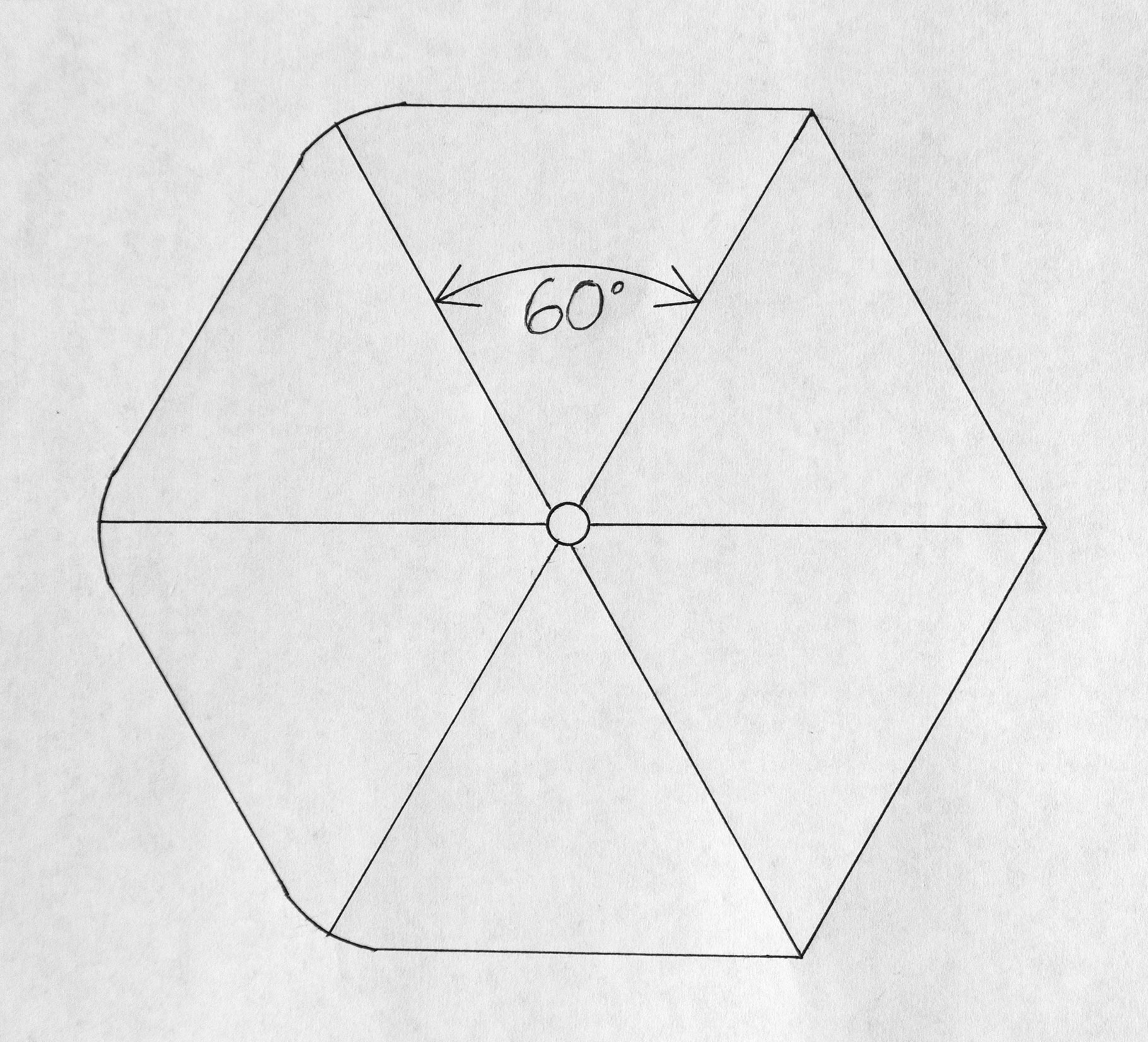

As was probably explained by Fash, the clerk who signed the sales slip that day, the six-sided split-bamboo rod with the H. L. Leonard logo had special qualities in spite of its strange appearance. The most obvious difference in the Leonard rod was its hexagonal shape. It had six sharp angles where the six flat bamboo strips were glued into joints. When moved briskly through the air in a casting stroke, the rod emitted a different sound than the one folks were used to hearing from round rods.

H. L. Leonard’s unique spiked-style ferrule design patented in 1875 and 1878. Photo by Jay Hupp.

The 1881 Leonard rod, in the lower half of the photo, has loose-ring line guides; the 1940s vintage rod at the top shows the snake-style guide. Also note the slightly rounded hexagonal joints on the Leonard rod as a result of sanding. Photo by Jay Hupp.

Although the technology was superior, Mills faced a marketing challenge in the rod’s strange appearance and casting sound. Both aspects were less than pleasing to traditionalists. That problem led the Leonard Company to compromise to some degree in early rod production by sanding off just a bit of the sharp angles to give the rod more of a round shape. The compromise must have pained Leonard, though, because it was he who had discovered that it was the outside fibers of the cane that gave the rod its superior strength. Sharp angles became less esthetically objectionable in later years, and eventually all split-bamboo rods retained their sharp-angle joints. That characteristic remains true of split-bamboo rods today.

The Leonard rod’s next obvious feature was the uniquely designed ferrule system, or connection fittings between sections. Here, too, Leonard was ingenious with his patented design from 1875 that eliminated moisture contact with bamboo at the bottom of the female ferrule, thus preventing rot in that area if the rod should happen to be put away wet. Also, the spiked-style ferrule design, patented in 1878, provided a more uniform stress distribution across the rod’s sectional joints. In an additional feature that appears as cracks where the ferrule joins the bamboo, the metal was intentionally cut to reduce the stress it would exert on the bamboo while casting or fighting a large fish.

Examining the rod today, we see that the materials, design, and quality of workmanship have withstood long and hard use. The ferrules are as strong and tight as they were in 1881. When the rod is taken apart, the ferrules pop as if they were new.

A less-than-unique feature of the Leonard was its being fitted with flip or loose-ring line guides. Although common at the time, this guide type gave way to the snake guide design early in the 1900s. The change came about primarily as a result of braided horsehair lines being replaced by silk. The snake guides were more efficient at passing the new casting lines.

So by the late 1920s, hardly anyone was putting up with the line drag induced by the loose-ring guides. However, one of the amazing things about John E. Calhoun’s rod is that it experienced ninety years of use without the loose-ring guides being updated to the snake design.

The diminutive logo engraved below the reel seat was one of the rod’s most subtle but distinguishing features. It read:

H. L. LEONARD

MAKER

W. MILLS & SON

N’ YORK

SOLE AGENTS

The logo’s wording is significant because it reflects something that the clerk at Mills & Son probably did not discuss with his customer that day in 1881. Without saying so, the logo indicates that the rod was made by Leonard, but Mills controlled its marketing and distribution. That’s because Leonard fell on hard financial times in 1877 and allowed Mills to invest in the company. In 1878, Mills moved into a 51 percent ownership position and caused the Leonard rod-making facility to relocate to Central Valley, New York, in the summer of 1881. From then on, the relationship was anything but comfortable for Leonard and his crew.

With an understanding of the technological improvements offered by split-bamboo construction and the new ferrule designs in mind, John E. Calhoun bought the H. L. Leonard rod on 23 December 1881 and left the Mills shop with the purchase receipt in hand after paying $30 cash. (Today new handcrafted split-bamboo fly rods sell for $2,000 to $7,000, depending on the maker.) The assumption that John bought the rod for himself is somewhat speculative; his brother Henry could have given it to him that Christmas. But if that were the case, it is unlikely that the purchase receipt would have accompanied the rod as a gift and then been available for discovery by John’s grandson 117 years later.

Today, most of the story of what likely happened in the Mills shop is told by the sales receipt and augmented by some insights into early bamboo rod making. What’s not told by the receipt is where John got the rest of the gear to go along with his new rod—like the reel, casting line, flies, and instructional materials for fly fishing.

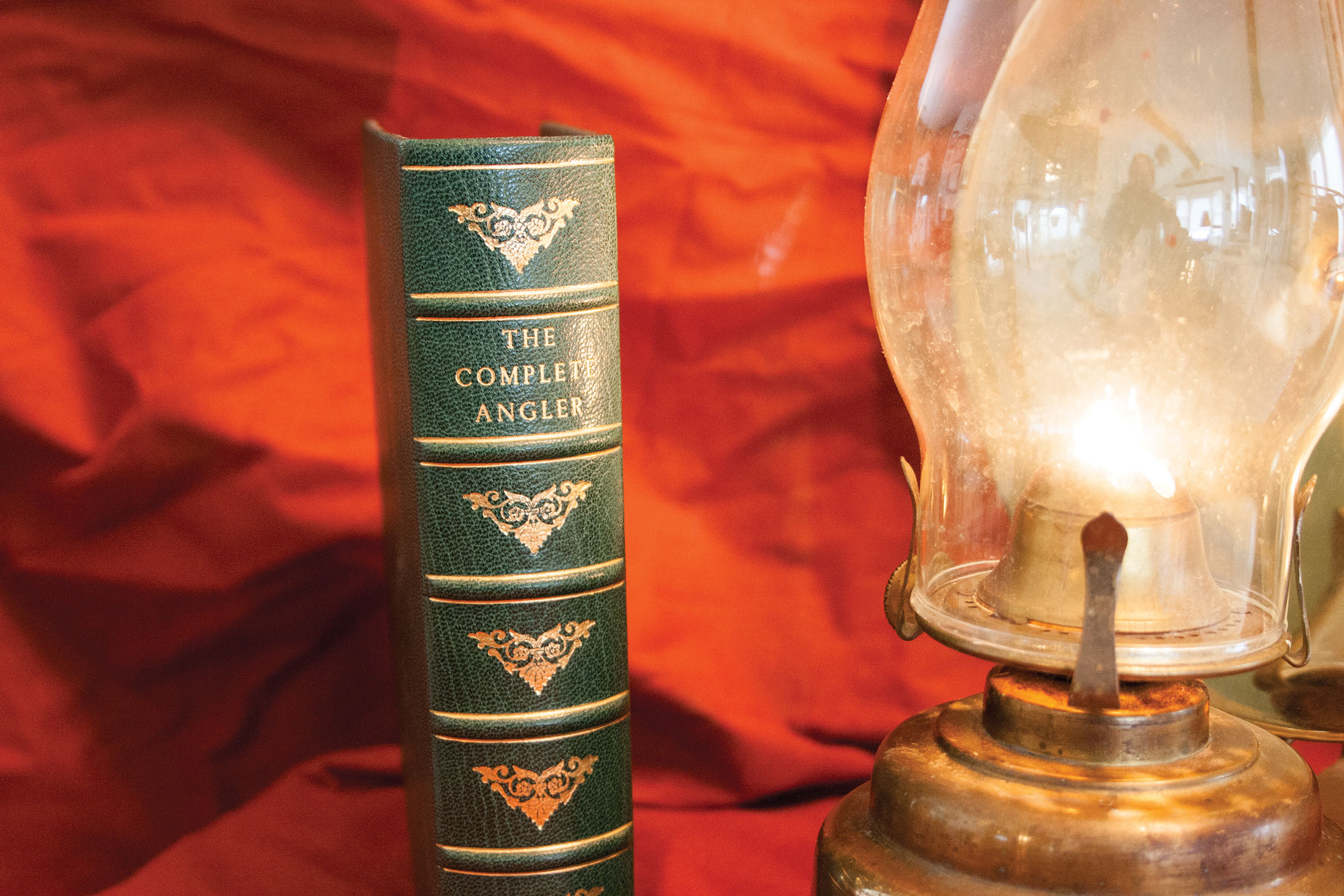

We are left to speculate that John may have already been an accomplished and well-equipped fly fisherman who was just buying himself a new rod for Christmas. The assumption is further strengthened by a third item that rests with the rod and its receipt today. John E. Calhoun’s copy of Izaak Walton’s The Complete Angler was an 1856 edition. The young man’s copy of Walton’s fishing bible could have been as old as twenty-five years in 1881. Was the book passed to John by his father, John C. Calhoun, along with other fishing skills and interests?

At any rate, the receipt obviously went back to school with John E., along with the rod, because it was found by his grandson in 1998 with other old stuff saved from Yale, such as 1881 laundry lists and baseball score books. According to his grandson (who also goes by John E. Calhoun), John E. “used the rod extensively—as you can see from its condition today” (letter to author, 23 May 2005). It saw use at the pond on his 650-acre farm in Cornwall, Connecticut.

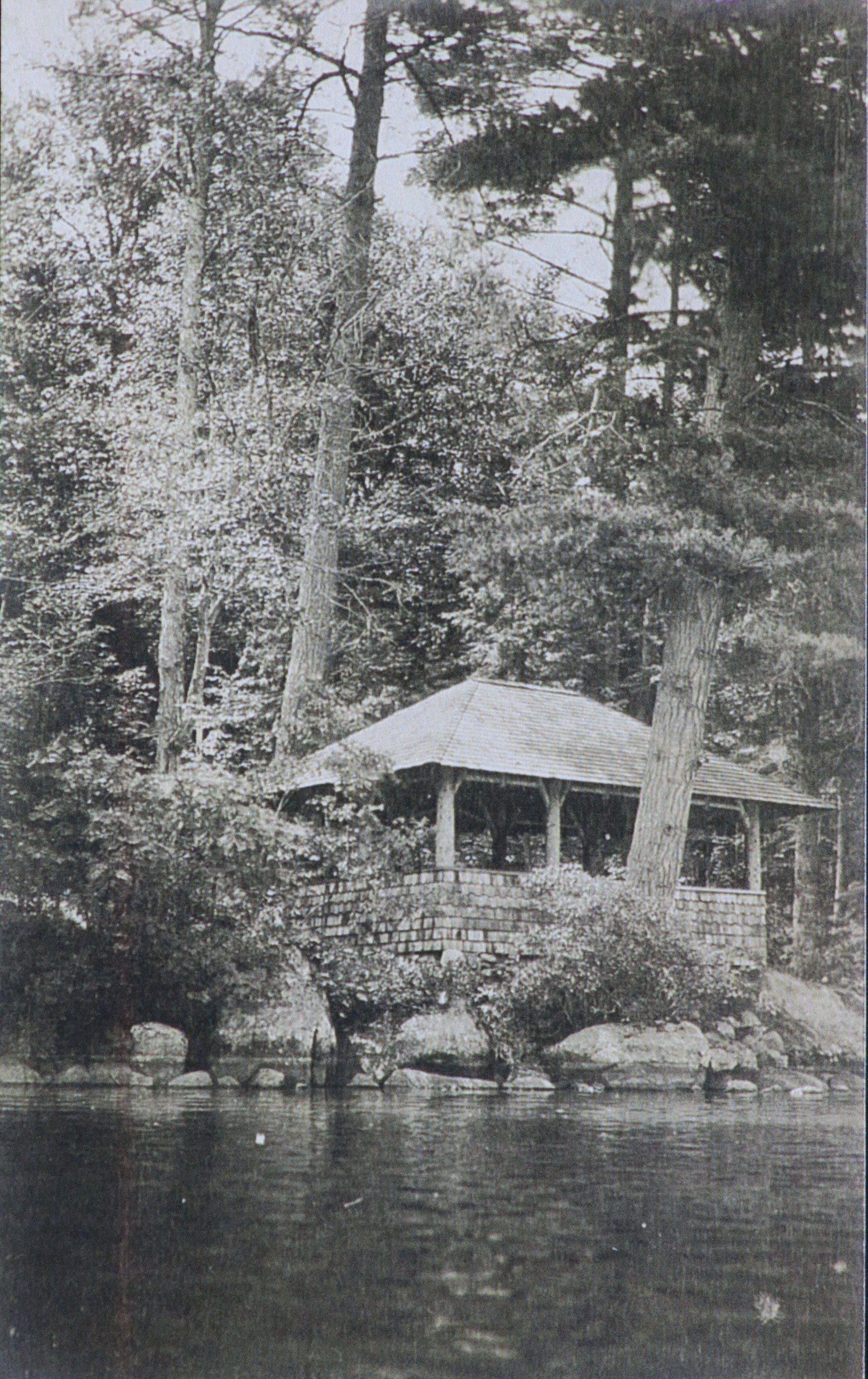

The rod was also fished by John E.’s son and grandson at the family summer camp on South Pond in the Adirondacks and at “The Nutshell” camp on Cream Hill Lake in Cornwall.

As the years passed, the rod was worked extensively by John E. until it was inherited by his son, Frank E., in 1940. Frank, in addition to running the dairy farm and raising a family, used the rod in the same local waters fished by his father as well as on several trips throughout the western United States after 1958. In the 1970s, Frank passed the rod to his son, who fished it in New Brunswick, Canada, for several years.

When John E. Calhoun’s grandson made the Leonard and the 1881 purchase receipt available at auction in 2005, I purchased them. In a later transaction, he added his grandfather’s copy of The Complete Angler to keep the collection together.

So with all of that, I recommend that you keep the sales receipt if you want to buy yourself a split-bamboo rod for Christmas. That way, your grandchildren too will have something to show and tell in generations to come.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2014 (Vol. 40, No. 4) issue of the American Fly Fisher.