By Gordon M. Wickstrom

POETRY, IT HAS BEEN SAID, is the most esoteric of the arts. So it’s remarkable to find fishing quite often invoked by poets to serve as metaphors or allegories. An outstanding example is the poet William Butler Yeats, as shown in the analysis here, first published in 1970 in the F.F.F. journal, The Flyfisher, by frequent contributor Gordon M. Wickstrom.

JOE A. PISARRO Former editor of The Flyfisher

Probably no sport has so vivid a life in literature as fishing. So particularly fly fishing, in both life and art that the compromised word “sport” has always been an uneasy generic name for what Izaak Walton called “the contemplative man’s recreation.” That fishing was the first and perhaps still is the only sport to inspire a masterwork of world literature in Walton’s Compleat Angler attests to this specialness. From our beginnings, we have attributed an important symbolic meaning to fish, fishing, and fishermen. In the sacred waters of our origins, the fish is soul or self; the fisherman is the divine fisher for souls or the human fisher for self- hood. Witness Christ’s call to Saints Peter, Andrew, James, and John to leave their nets and be fishers of men and Christ’s own symbolic identification as a fish.

In a strange way, fishing and the attendant killing have never been associated with the carnage, blood lust, and moral risk that some sentimental persons and many zealots have often attributed to land hunting. The fish as prey is at once more spiritual and less particular; his life does not appear to be his own as is the case of the pheasant, the deer, or the fox. He belongs to a different realm of consciousness, another element, abstract and formal, abundant with ritual significance.

The fisherman clearly operates in a different order of things from the hunter or any other “sportsman.” His solitary pursuit has archetypal substance, and when he is most truly “contemplative,” and when he fishes the fly, he is most apt to be open to and aware of the ancient and profound meaning.

In a strange way, fishing and the attendant killing have never been associated with the carnage, blood lust, and moral risk that some sentimental persons and many zealots have often attributed to land hunting. The fish as prey is at once more spiritual and less particular; his life does not appear to be his own as is the case of the pheasant, the deer, or the fox. He belongs to a different realm of consciousness, another element, abstract and formal, abundant with ritual significance.

The fisherman clearly operates in a different order of things from the hunter or any other “sportsman.” His solitary pursuit has archetypal sub- stance, and when he is most truly “contemplative,” and when he fishes the fly, he is most apt to be open to and aware of the ancient and profound meaning.

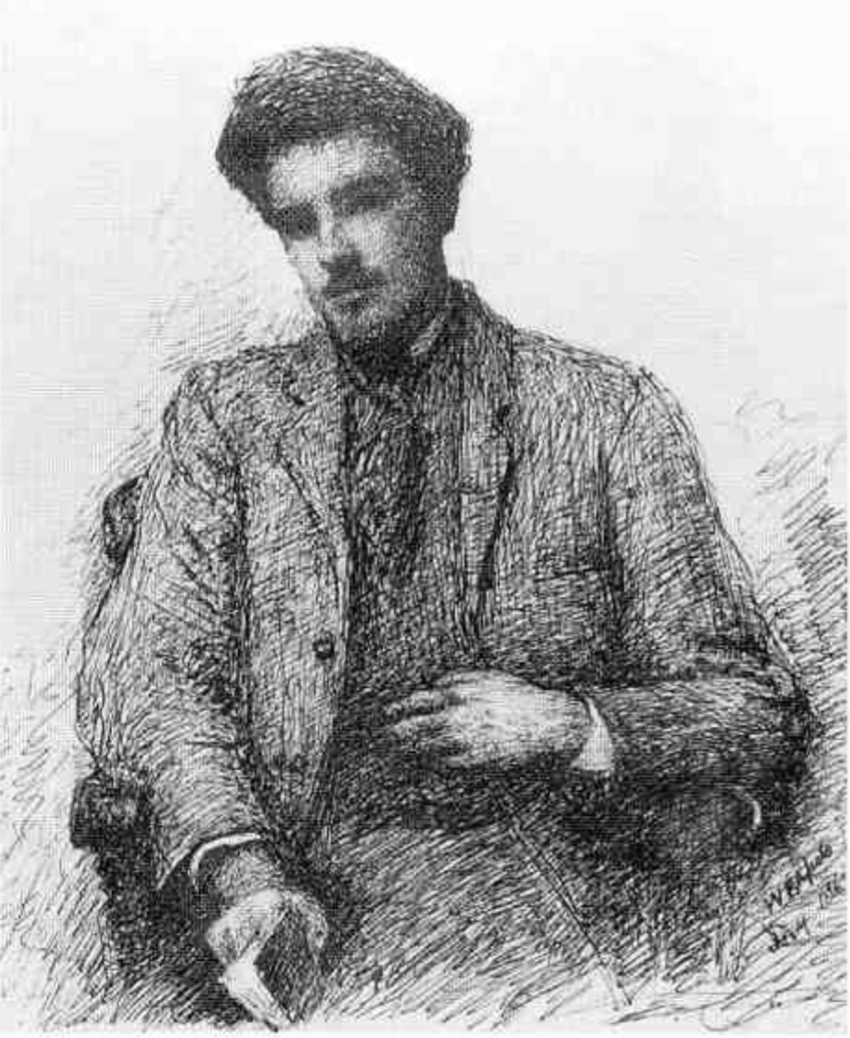

Confident of this specialness about fly fishers and their flies, William Butler Yeats, arguably the greatest poet of our century (1865-1939), used the fly fisher and his craft as a central and controlling image in several of his most impressive poems. His output over half a century dealt with his native Ireland; Ireland of ancient mvth and modern revolutionarv politics, of nature and art, of passion and hate, his loves and occult philosophy.

Yeats was a native of the west country, of County Sligo, and though he lived his adult years in London, Dublin, and finally in his tower-home in County Galway, he remained faithful to his idea of himself as a Sligo man-Sligo, twin- shouldered by Donegal to the north and Mayo to the south where perhaps the finest of all the splendid Irish fishing for both trout and salmon is still to be found. Though he fished almost exclusively in his boyhood, and then only occasionally, he learned enough during those Sligo years and observed enough later to make his grasp on angling accurate and sensitive.

Fly-fishing readers of his poems find these images right on the mark, evocative of their own best moments on the water. The reader validates the image with, “Yes, that’s the way it is.” Such validations of experience are at least one of the essential functions of poetry.

Yeats describes in an early poem, “The Song of the Wandering Aengus”, how:

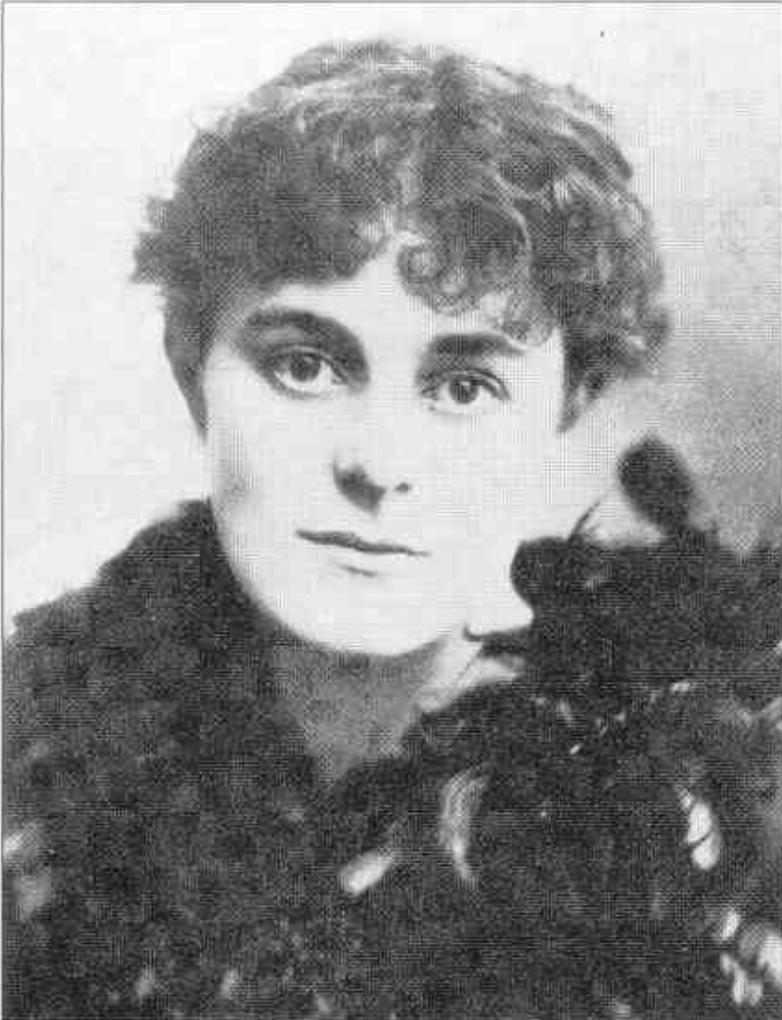

Irish revolutionary, actress, and writer Maud Gonne was the inspiration and love of Yeats’s life. Her impassioned beliefs and unflagging energy landed her in prison on more than one occasion. She refused Yeats’s offers of marriage but remained a lifelong friend

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickring out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.’ 1(p.57)

The delicate and lovely poem continues through the vision of a beautiful girl (not unusual in angling lyrics: remember Walton’s milkmaids) and ends in the poet’s promise to hunt for the girl through all that western land “till time and times are done.”

But other places and sterner tasks were to call the poet away from his youthful, Celtic dreaming and cause him to transform his angling image. Ireland had to be recalled to her past national and cultural glory; the English oppression had to end; the Irish had to revive their literature and create a drama. Paradoxically, the literary efforts, which Yeats sparked and led, had to begin in London among the exiled Irish intellectuals there and come home to Dublin around the turn of the century. This huge and ultimately successful undertaking held many moment of & illusionment and disappointment for the poet. The Irishman, who in too many cases was immune to the call of greatness from the poets, revolutionaries, even exquisite women like Maud Gonne, Yeats’s first and great love, seemed to need no enemies, even the British.

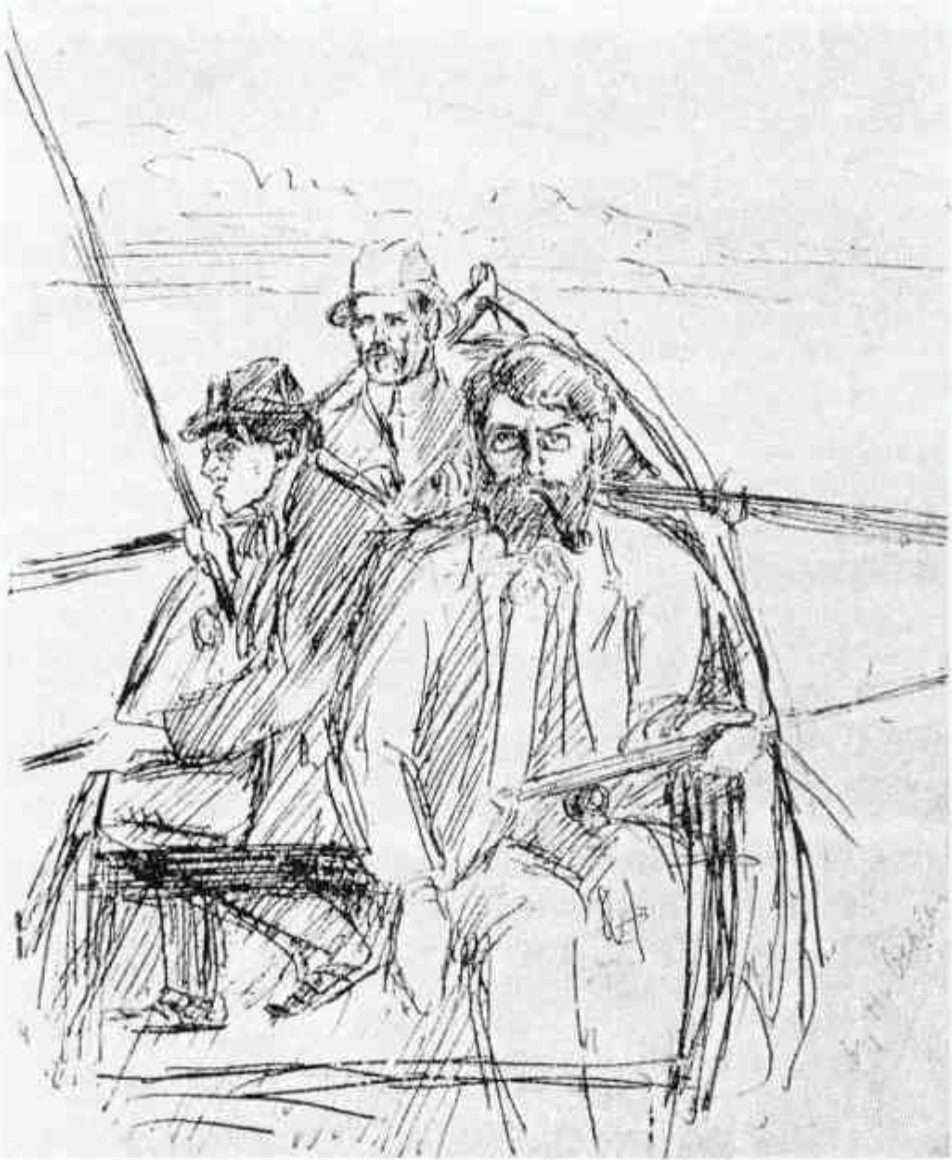

The failure of Ireland to rise to the challenge of his vision disappointed Yeats, often nearly to despair. In 1919 he responded with the poem “The Fisherman” in which the gray, Connemara fly fisher becomes a symbol for the controlled passion (a useful description of fly fishing) and the ideal of Irish manhood for the modern dilemma. The poem comes round to Yeats’s hope, his intention one day to make a poem of equal intensity and skill to the fisherman’s art:

From A Guide to Coole Park, Co. Galway: Home of Lady Gregory

Although I can see him still,

The freckled man who goes

To a grey place on a hill

In grey Connemara clothes

At dawn to cast his flies,

It’s long since I began

To call up to the eyes

This wise and simple man.

All day I’d looked in the face

What I had hoped ‘twould be

To write for my own race. . .

The poem goes on to a catalog of the “other” Irishmen, self-defeating cravens, drunks, knaves, and clowns who spoil all they touch. Then the poem returns for solace to the fisherman:

Bronze statue of William Butler Yeats located outside the Ulster bank on Stephen Street in Sligo, created by Rohan Gillespie

Maybe a twelvemonth since

Suddenly I began,

In scorn of this audience,

Imagining a man,

And his sun-freckled face,

And grey Connemara cloth,

Climbing up to a place

Where stone is dark under froth,

And the down-turn of his wrist

When the flies drop in the stream;

A man who does not exist,

A man who is but a dream;

And cried ‘Before I am old

I shall have written him one

Poem maybe as cold

And passionate as the dawn.’ (pp. 145-46)

And so one of the great Poems of the language at once seems to crystallize the fly-fisher’s experience, his energy, his solemn role in a larger experience, and its close kinship to poetry “as cold and passionate as the dawn.”

Ireland has a built-in receptivity to such the Irish are a fish-conscious people, long associating fish with a stable economy, food, and sport as well as symbolic life. In myth, the salmon is identified with wisdom and a metaphysical life.2 In his notes to early Poems, publishedin Crossways, Yeats wrote:

The little Indian dramatic scene was . . . (Anashuva and Vijaya) about a man loved by two who had the one soul between them… It came into my head when I saw a man at Rosses Point carrying two salmon. “One man with two souls,” 1 said, and added, ”0 no, two people with one soul.” (p.447)

This is the kind of teasing past thought that the fish and fisherman have for the Irish mind. The salmon has a heroic shape – an epic, mythic life, while the trout belongs to the world of the lyric, to the experience of love, a congenial nature and a reflective, if gray, integrity.3

In the complex poem “The Tower,” the aging poet inventories his diminish- ing vigor and regrets that he must leave Ireland to “young upstanding men” while he retreats to a reclusive study of the dignified abstractions suitable for a proper old poet. The young men to whom he resigns his power are those:

Innisfree, Lough Gill

That climb the streams until

the fountains leap, and at dawn

Drop their cast at the side

of dripping stone;…

I leave both faith and pride

To young upstanding men

Climbing the mountain-side,

That under bursting dawn,

They may drop a fly; (pp. 196-97)

Earlier in the poem, anxious to escape the bondage of age, he cites his boyhood again:

…when with rod and fly,

Or humbler worm, I climbed Ben Bulben’s back

And had the livelong summer day to spend. (p. l92)4

It was a time of passionate imagination, but not so passionate as that of the old age now “tied” to him by the world. Reluctantly, he would give way to younger, stronger men.

But such men were hard to find: he had been one himself, he argues in the poem, before the “sedentary trade” took over his life. Looking back on it all brought forth the famous poem “Why Should Not Old Men Be Mad?” In it he began:

Why should not old men be mad? Some have known a likely lad

That had a sound flyfisher’s wrist

Turn to a drunken journalist;

A girl that knew all Dante once

Live to bear children to a dunce; (p. 333)

He recalls everything that caused him grief: his own Maud Gonne- for him a modern Helen of Troy, the success of bad men, failure for the good, naivete of the young, Ireland’s resistance to her new potential. The image of sanity and purpose, of controlled passion is in that fly-fisher’s wrist, its downturn over pools among the rocks as the flies follow the line’s tight loop toward the fish.

Regardless of how frustrating and unsatisfactory the confused events of our public lives become, whether in Yeats’s new Ireland or our own more Los Angelized country, there’s promise of another way- that ancient, youthful fly fisher still stands there in the cold, gray Connemara dawn, casting his flies from the past into the future to a prey that is not a prey at all, but a quest, a mystery, a symbol of the fly fisher’s own soul.5

Endnotes

- Quotations from the poems are taken from The Collected Poems of W B. Yeats (New York: Macmillan, 1961). Page numbers given by the quotes are from this edition.

- In his play Deidre, Yeats has his heroine compare the King’s deception with “Hackles on the hook.” Interesting also to the angling entomologist is the mayfly paternity (according to one version of the myth) of Cuchulain of the Red Branch legends, greatest of all the Irish heroes.

- The ideal condition of nature for men is the one ideal for trout.

- Ben Bulben is that great mountain-mesa in the north of County Sligo, close to the Yeats an- cestral home and in whose shadow he lies buried at Drumcliff Church.

- Other poems to look at are “The Stolen Child,” “The Ballad of Father O’Hart,” “The Fish,” “The Blessed,” “The Wild Old Wicked Man,” and “The Long-Legged Fly.” Many more poems, though not presenting the fisher directly, deal with the world of stream and lake, of fish and water- bird, where the fisherman is implicit, native, and welcome.

This article first appeared in the Spring 1994 (Volume 20, No. 2) issue of the American Fly Fisher.