Restoration and Sense of Place in the Nineteenth Century

He, who is pent up in a town, vexed by the excitements of the day, and driven, in spite of himself, to late and irregular hours, could get profit every way, if at times he would seek the purer air, free from the city’s smoke, and with his rod as a staff, climb the hills, and ply his quiet art in the brooks that wash the mountain side, or wander through the green valleys, shaded by the willow and the tasseled alders.

—George Washington Bethune, 1850

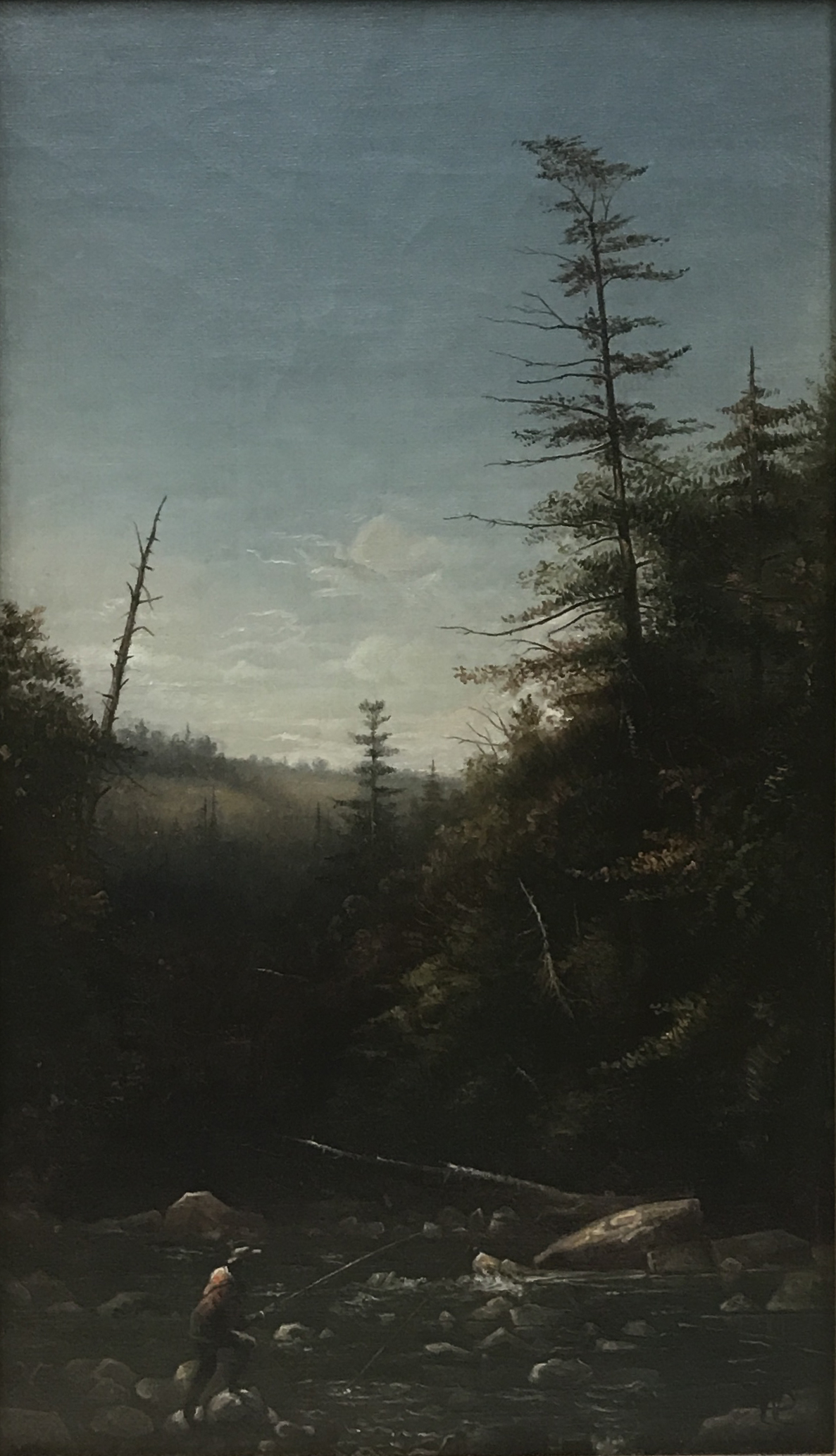

Nineteenth-century Americans lived through significant milestones that disrupted traditional connections to the natural world. The Industrial Revolution altered the ways of life, and oppressed indigenous communities; Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution challenged popular beliefs on existence; and the Civil War left widespread grief after communities lost their youth in battle. By the late half of the century, figures in the landscape within American art were flooded with an emotional realism that capture a country trying to restore traditional relationships with nature and rebuild a sense of place within a new cultural terrain.

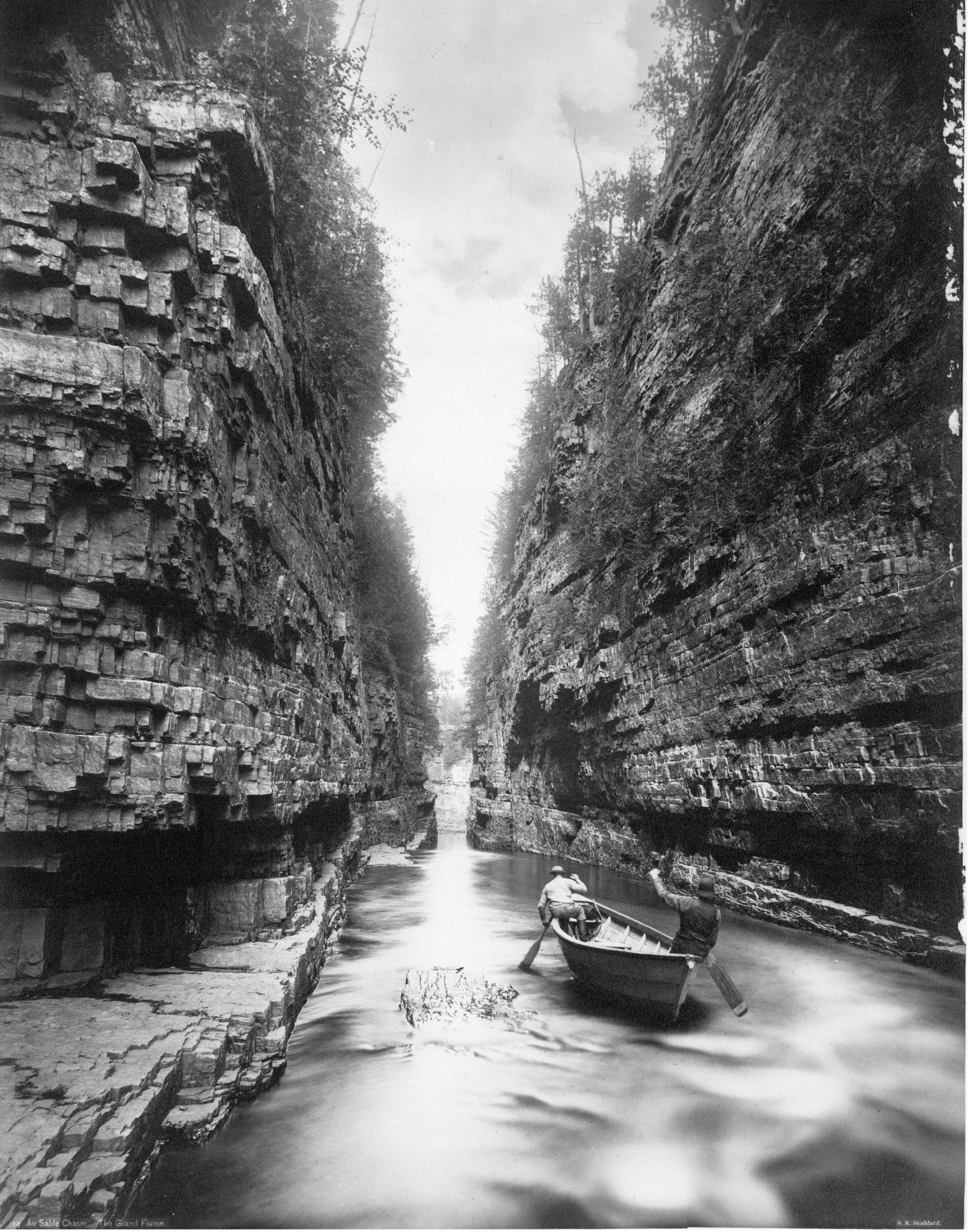

The American wilderness became a popular destination to escape the stresses of industrialized society and pursue a refined way of life. Railways and steamboats made way for anglers, artists, writers, and vacationers to easily access remote areas, and the countryside became speckled with vacation homes, artist colonies, communal farms, fishing clubs, and rural retreats. Among other outdoor activities, angling rose in popularity for the physical, mental, and spiritual benefits of reconnecting to the natural world.

The country’s growing interest in authentic experiences outdoors was mirrored in American art, and artists left their studios to study the scenes and lifestyles in the rural North American wilderness. Following in the steps of European naturalist and realist painters, a growing number of American artists painted en plein air to convey variances in natural light, often including figures of people or wildlife within the landscape to evoke the sensations of being immersed in nature. It seems likely that American artists encountered the angler casting into the rocky streams and wooded lakes of North America, already versed in the landscape that artists were beginning to realize.