Carrie Gertrude Stevens

(1882–1970)

Carrie Gertrude Stevens revolutionized the world of fly tying at the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century. Stevens was born Carrie Gertrude Wills in Vienna, Maine, and she stayed in Maine her entire life, never traveling beyond its borders. Stevens moved to Mexico (Maine) and met and married her husband, Wallace, in 1905. He was a fishing guide, so the couple moved to the Rangeley Lakes region. They settled into their own home by 1919 near the Upper Dam.

Stevens had fished with bait throughout her life, but on 1 July 1924, she decided it was time to create a fly of her own and test it in the Upper Dam pool. A friend, noted duck decoy carver and angler Charles “Shang” Wheeler (1872–1949), had shared a streamer fly with Stevens in 1920; Wheeler tied the fly based on an English pattern, and he encouraged her to try her hand at the art. On that particular day in 1924, Stevens resolved to simulate a smelt in the water, and she tied gray feathers onto a hook. She marched to the pool and began to cast, catching some salmon and trout. A little bit later she got a bite, struggled for about an hour, then landed a brook trout that weighed 6 pounds, 13 ounces, and measured 243⁄4 inches; Steven’s brook trout was the largest taken in thirteen years at the Upper Dam pool. The pattern she created was Shang’s Go-Getum.

She entered her catch in an annual fishing contest held by Field & Stream magazine and took second place. The following year, in 1925, the magazine’s editor decided to publish Stevens’s written account of her trophy catch. The sentence “He was caught with a Thomas rod, nine feet in length, a Hardy reel, an Ideal line, and a fly I made myself” was read around the world (Ladd Plumley, “Tales of Record Fish and Fishing,” Field & Stream [September 1925, vol. 39], 95–96). Orders for this fly began to arrive immediately, and Stevens suddenly had a new career.

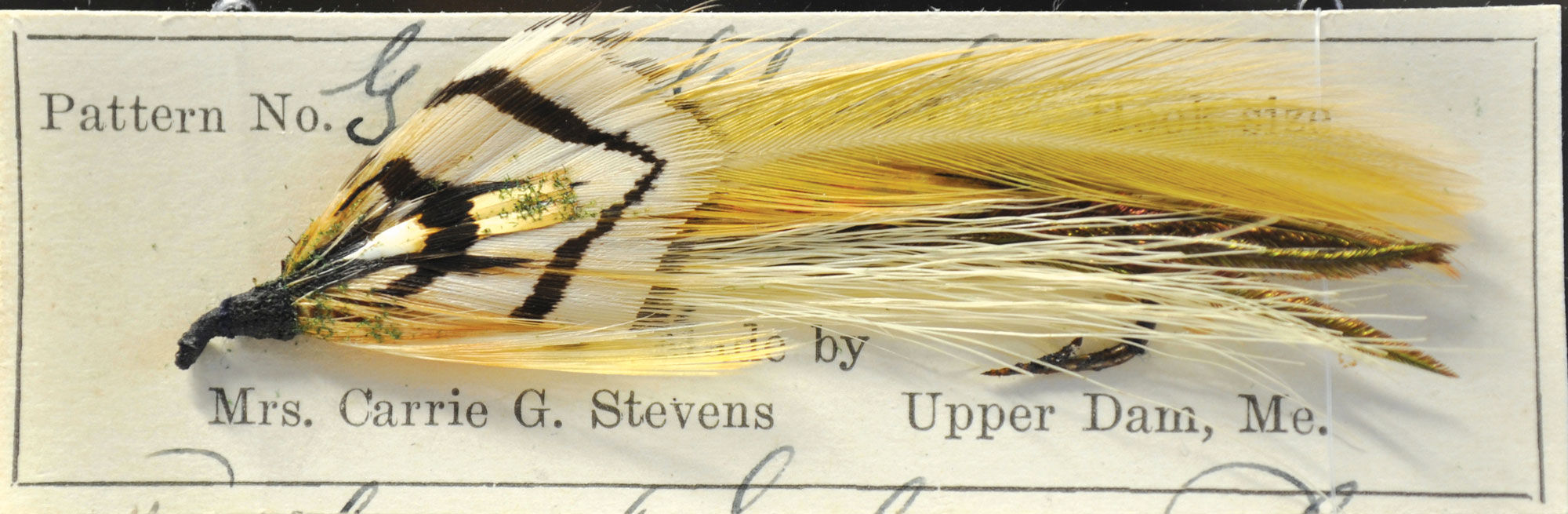

Rangeley Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies opened shop at the Stevens’s home, but Stevens viewed this as a side business; maintaining both her household and her husband’s guiding service took priority. The fly that landed her record brook trout quickly evolved into a more refined pattern, the Gray Ghost, and was the most requested of Stevens’s work. She had private clients who would submit special requests to her, but she also sold her flies to stores and camps in the Rangeley area. Her marketing consisted of fly cards with her name, pattern number, and hook size. She opted to use half hitches instead of a vise while tying. Stevens was very protective of the dozens of new patterns she created and the thousands of streamer flies she dressed; in fact, she never allowed anyone to watch her work.

Carrie Stevens lived until 1970, but by 1953 it was apparent to her that both her health and her husband’s health were deteriorating, making it impossible for her to continue with her business. She sold her supplies and forwarded her client list to Wendell Folkins. In 1954, Folkins and friend George Fletcher were the first people to ever witness Stevens dressing a fly. Both knew this was a monumental event. Leslie K. Hilyard, who coauthored a book about Carrie Stevens, became the third proprietor of Rangeley Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies in 1996.

Stevens standing beside the business sign in front of her Maine home.