By Jerry Gibbs

For many, saltwater fly fishing has seemed a relatively recent phenomenon that burst onto the angling stage between the late 1950s and the 1970s and has continued to expand influence since. In fact, it is quite ancient. Listen to angling historian Dr. Andrew N. Herd:

Saltwater fly fishing has gone through so many renaissances that it is easy to assume that every generation sets out with the perverse intention of reinventing it. There’s a great deal of dispute about who dipped the first fly in the sea, but it happened at least two thousand years ago, because Aelian [Roman author-teacher Claudius Aelianus] describes it quite clearly: “One of the crew sitting at the stern lets down . . . lines with hooks. On each hook he ties a bait wrapped in wool of Laconian red, and to each hook attaches the feather of a seamew.”1

Captioned “Fish-rocks at mouth of Columbia River photographed by B. C. Towne,” this photo from the display panels that Mary Orvis Marbury brought to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago is one of the only images in those panels that features a saltwater setting. Although it’s difficult to tell for sure, it appears as if a few of the figures standing on the large rocks on the right are holding fishing rods. From the collection of the American Museum of Fly Fishing.

In North America, the earliest documented date for saltwater fly angling was recently uncovered in a letter of 28 October 1764. The writer, Rodney Home, a subaltern of the then–recently appointed governor of the West Florida Colony, quickly and successfully swam his flies in his newfound local waters. “We have plenty of salt [?] water trout & fine fishing with fly . . .”2 he happily reports.

By the 1800s, pioneering anglers on both the east and west coasts were taking their freshwater trout and salmon tackle to bays, coves, and estuaries—even surf—to discover the effectiveness of bright, sometimes well-gnawed salmon flies and learn the limitations of tackle built for fresh waters. Sea-run brook trout (salters) and striped bass were popular as early as 1833, as reported in Natural History of the Fishes of Massachusetts by Jerome V. C. Smith, who regularly fished for those salters from points extending off Cape Cod’s south shore.3 On the West Coast, saltwater bays—the Columbia River’s mouth was prime—were giving up returning Pacific Ocean salmon to the long rod, as colorfully described by artist-engineer Cleveland Rockwell,4 and there was even quite limited fly fishing on the Texas Gulf Coast.5 More activity in the sport was seen as pioneering anglers explored the East Coast, sampling the great species variety around Florida’s still little-developed shores, especially those on the state’s western side. Dr. James Henshall was catching redfish, sea trout, snook, jack crevalle, bluefish, ladyfish, and tarpon to 10 pounds on the fly along both lower Florida coasts in 1878, publishing an account of his adventures in Camping and Cruising in Florida, 1884.6 The work appears to be the first to include accounts of tarpon fishing using freshwater fly tackle. Ten years later, author Frank S. Pinckney, in The Tarpon or “Silver King,” credits New York physician George Trowbridge as landing a 1-pound, 3-ounce baby tarpon on a fly.7 Trowbridge fished for multiple Floridian species, enjoying night forays for channel bass in Sarasota Pass. A. W. Dimock, whom we’ll focus on shortly, reports viewing Trowbridge in Sarasota Bay fishing alone and “capturing from his light canoe . . . a twenty-two-pound channel bass and a sixteen-pound cavally [jack crevalle], all on light fly-rods.”8

Pickney’s slim volume (today a collector’s item), a delightfully opinionated work in which the author quotes a learned judge commenting that any maker of faulty tarpon tackle ought to be “drawn and quartered,”9 fired the growing popularity of tarpon hunting, although it was merely one factor. Rail lines and steamship routes were opening the Florida wilderness at a fast rate. Florida angler and conservationist J. P. Wilson describes the inroads thusly:

Fishing destinations at the Halifax River, Indian River, Charlotte Harbor, Lake Worth Inlet, Jupiter Inlet and Indian River were now accessible through rail heads at Punta Gorda, Titusville and Daytona. These rail spurs had pushed through the wilderness from the Florida Tropical Trunk Line’s terminal in Jacksonville. By 1889 there were over 650 miles of railways and 250 miles of connecting steamship lines advancing toward remote Florida coastal destinations. Punta Gorda on Charlotte Harbor was the end of the rail line for Southwest Florida. A short boat ride through the inside passage of Pine Island down to Punta Rassa took one to The Tarpon House, believed to be the oldest tarpon fishing resort in America, and for that matter, probably the world.10

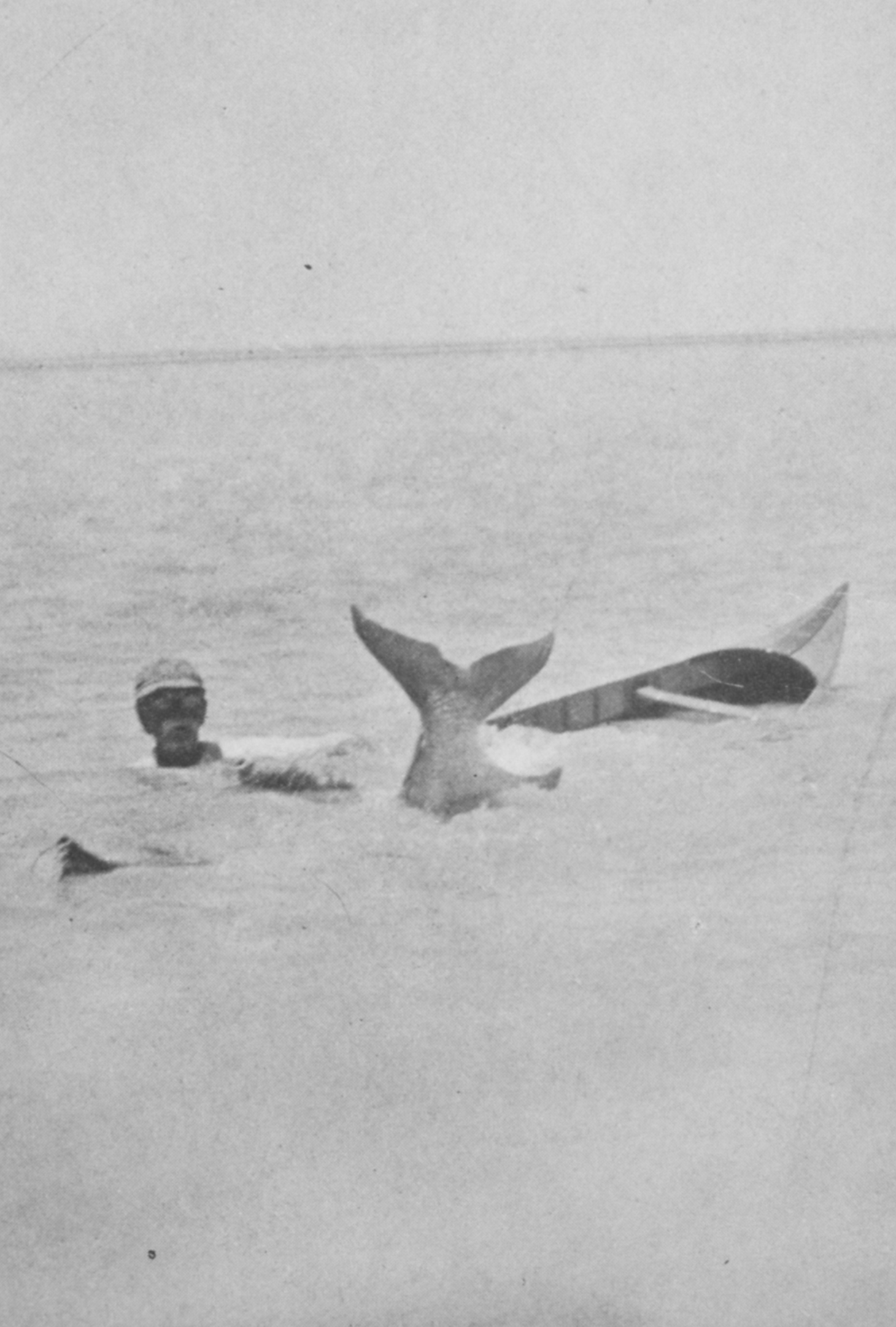

A. W. Dimock enjoying a swim with Florida manatee friend. Used with permission from Florida Photographic Collection. Photo by Julian Dimock; used in their book Florida’s Enchantments, published in 1908.

A. W. [Anthony Weston] Dimock’s saltwater fly sport included both tranquil wade fishing and physically rough encounters with any large specimen that would eat his flies, the latter experience paralleling his volatile business career. Accepted as a member of the New York Stock Exchange before he was twenty-one, Dimock quickly dominated gold markets. At thirty, he was president of several steamship lines, controlled a telegraph company (the Bankers and Merchants Telegraph Company), and became a partner of Maquand & Dimock, bankers and brokers (which eventually became A. W. Dimock & Company). Then, suddenly, he fled the city, headed west, and for several years simply hung out with both ranchers and Indians, hunting and fishing. He thrice made and lost millions on Wall Street. He was $4 million in debt, though living in fine style at the Peakamoose Clubhouse in the Catskills, where in September 1894 he and his family were physically evicted in the driving rain.11 The man continued to pull releases from creditors, write youth adventure books, and finance fishing safaris before dying suddenly in his Happy Valley country home in the Catskills on 13 September 1918.12

Some of Dimock’s adventures could have been plucked from a Teddy Roosevelt journal. His recollections in articles and books are arguably the best in capturing the zeitgeist of this early period of saltwater fly fishing; certainly, they are entertaining. Dimock launched numerous saltwater fishing safaris along Florida’s coasts beginning at least in 1882, three years before tarpon were declared a game fish. He fished and explored from Homosassa down to Boca Grande, south to Cape Sable, poking up numerous Everglades rivers and even making a foray over to Bahia Honda in the Keys. To a great extent, he lived off the sea and land, camping, enduring horrendous storms, and encountering Florida panthers, bear, moonshiners, sharks, and, of course, tarpon. During a trip that resulted in the 1911 publication of The Book of the Tarpon, he also employed a motorized coastal sailing vessel, the Irene, as a mother ship to augment shore camping.

Although Dimock used all manner of tackle—from hand lines to heavy rod and reel and occasionally harpoon—a great deal of his sport was with an 8-ounce fly rod, with which he took the usual grab bag of inshore species. In an article titled “Saltwater Fly Fishing,” he brands 2-pound ladyfish as the “Ultima Thule” of fly-rod sport; by the time his next tarpon safari is done, three years later, he has changed his mind.13 Here’s Dimock from The Book of the Tarpon:

The tarpon meets every demand the sport of fishing can make. He fits the light fly-rod as no trout ever dreamed of doing and leaps high . . . a hundred times for every once that a brook trout clears the surface. . . . When grown to the size of the average man he is no less active. . . . To one who has known the tarpon, the feeble efforts of the salmon to live up to its own reputation are saddening. . . . Time would be wasted in seeking for comparison among lesser fish than salmon. . . . Played gently from a smooth-running reel . . . his capture is not beyond . . . a robust child . . . or the great fish can be fought furiously . . . they have landed on my head, caromed on my shoulders, swamped my canoe, and one big slippery form dropped squarely into my arms.14

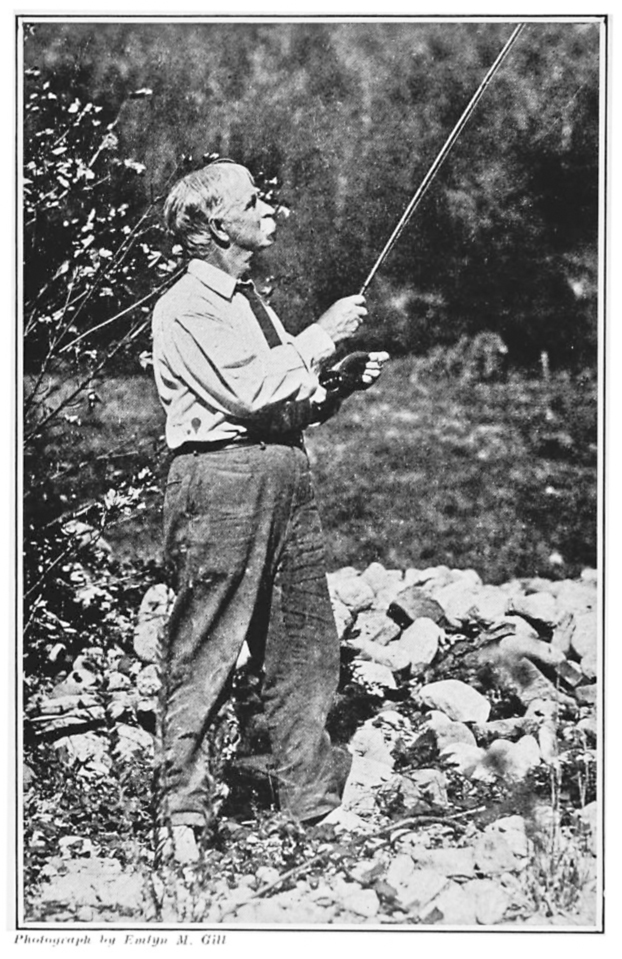

A. W. Dimock frontispiece from Wall St. & The Wilds. Dimock was a trout angler as well as saltwater fisherman. Photo from original book in the Cornell University Library, published 1915, New York, Outing Publishing Co. Photo by Emlyn M. Gill.

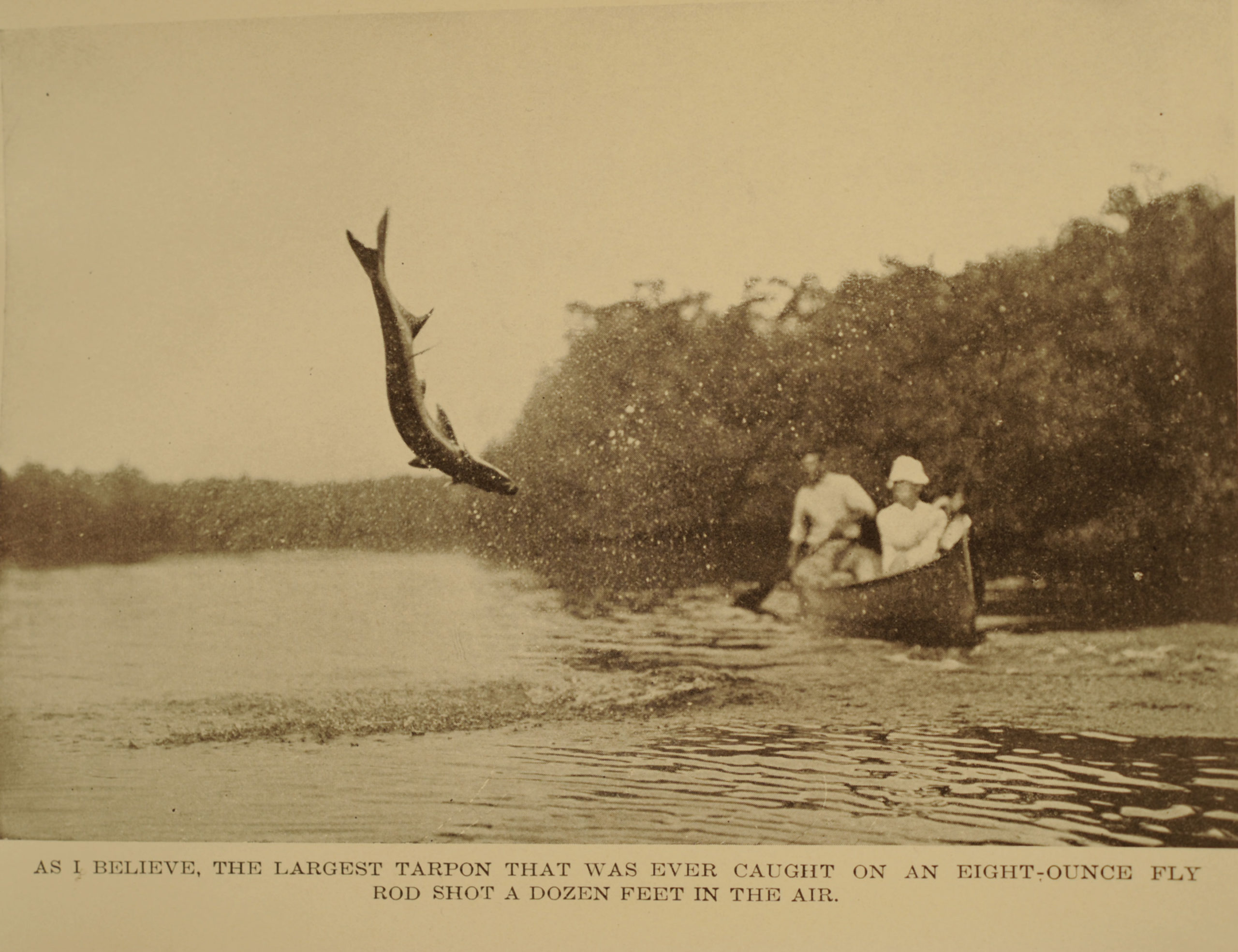

After an hour fighting his largest fly-rod tarpon up and down Turner’s River, Dimock’s fish was now well out into Chokoloskee Bay and still not ready to quit. From A. W. Dimock, The Book of the Tarpon (London: Frank Palmer, Red Lion Court, 1912), 140.

Note Dimock’s canoe reference. Virtually all of his tarpon fishing took place from a light Canadian Peterborough canoe, usually paddled by a hired captain while Dimock fished. Occasionally he took over paddling duties, letting his captain fish simply to vary the strain on his muscles following successive tarpon battles. The ninety-three photographs illustrating The Book of the Tarpon were made by Dimock’s son, Julian. They are remarkable considering that they were taken using glass-plate technology, his equipment a 17-pound view camera and a 6½-by-8½ reflex. Julian followed his father in the Green Pea, a short, wide skiff with tiny motor run by a young assistant named Joe. The verbal altercations between father and son—and sometimes even A.W.’s captain—smack of a contemporary high-maintenance film director bullying his actors to get a scene down; in this case, boat-angler-plus-leaping-tarpon positioned within the window of best light. When Julian had run out of plates for the day, Dimock generally quit fishing while the younger retired to shore with “tent and blanket piled over me to shut out light and air, while they kept mosquitoes and deadly heat in. I’d do it again . . . ”15

Dimock was occasionally knocked from his canoe fighting tarpon. His captain and son were not immune either. From A. W. Dimock, The Book of the Tarpon (London: Frank Palmer, Red Lion Court, 1912), 188.

On more than a few occasions, attempts at keeping the separation of the angler and leaping tarpon at a minimum for the camera resulted in canoe capsizes, sending both angler and captain into the water. Several times sharks severed in two the tarpon A.W. was fighting, at least once catapulting the captain from the canoe, whereupon Dimock frantically paddled for the shallows, towing his captain who, though still of the belief that sharks would not attack a human in local waters, admitted that he was “scared blue.”16 Dimock’s observation of high shark numbers along the outer Keys led him to recommend passing up this area for the sake of avoiding attacks on hooked tarpon.

Dimock kept scrupulous records of his fifty-two-day photo trip, which resulted in The Book of the Tarpon. He reported 334 tarpon taken, 63 of them on an 8-ounce fly rod. He warned that “a stiff, single-action tournament style of fly-rod fits the agile baby tarpon . . . while a withy, double-action article couldn’t follow for a minute the fish’s changes of mind.”17

Much preferring that his fly-rod fish ranged from 2 to 10 pounds, he nonetheless brought to hand numerous young tarpon to 20 pounds and one record-setting Goliath. At the south end of Chokoloskee Bay in the Turner’s River, Dimock had just released a 10-pound fish using his 8-ounce fly rod when he hooked up with a huge tarpon that immediately leaped three times in rapid-fire succession then ran out most of his line: “I needed more yards than I had feet of line to offer a chance of tiring this creature whose length exceeded mine by a foot . . . I yelled to the captain to paddle for his life, regardless of the fact that the man was already putting in licks that endangered it.”18

Dimock’s tarpon was at the time the largest ever taken using a fly and properly casting. His son Julian, however, finished the fight. From A. W. Dimock, The Book of the Tarpon (London: Frank Palmer, Red Lion Court, 1912), 189.

An hour into the fight, Dimock and his captain were well out into the bay but always keeping within 200 feet of the tarpon. Because of the inability to apply significant pressure using his outfit, Dimock’s strategy was to have his captain paddle quickly to the fish while line was reeled in, then impart a sharp twitch, which usually caused the fish to make another leap, tiring it. At one point at close range, the tarpon surged beneath the canoe while Dimock thrust his rod into the water, the rod tip swinging, not breaking, as the captain managed to sweep the canoe into pirouette. Finally, admittedly exhausted, Dimock offered the rod to Julian, who had exposed all his photographic plates. The two changed places. With Julian on the rod, the tarpon shot upriver, under a bank, and back down to the bay, where it finally rolled on the surface. The captain feared a capsize if he tried to boat the fish, to which Julian replied: “Get it in the canoe first and capsize afterward all you want, only don’t move till I measure it.”19 Once taped, the captain’s attempt at boating the fish failed as the fish surged away. Incredibly, the hook held. The second boating attempt was successful: the fish slid into the canoe but with one more contortion levitated, then pinwheeled out, flipping the canoe and dumping Julian and the captain into the bay. The tarpon measured 6½ feet and was estimated at 140 pounds. Dimock believed it the largest tarpon then taken on the fly rod, despite the double-teaming angling effort. It would remain so for some time.

After A.W.’s death in 1918, Julian gave up photography, having published several successful books on nonsporting subjects. He moved with his wife to Topsham, Vermont, where he became well known for high-quality apples and seed potatoes. The Dimock family publications were housed with the Vermont Historical Society in 1997. Included is the entire magazine collection in which A.W., Julian, and their respective spouses are represented through contributed articles or photographs. The collection includes a variety of travel, recreation, nature, and country living periodicals published from 1903 through 1921.

The stage was set for an acceleration in the development of saltwater fly fishing from the 1930s through the 1950s and beyond. Significant events—including technical breakthroughs in the Northeast, Southeast, and West Coast—will be explored in an issue of the American Fly Fisher next year.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2012 (Vol. 38, No. 3) issue of the American Fly Fisher.

Endnotes

- Andrew N. Herd, “A Fly Fishing History” (with a quote from Aelian, On the Nature of Animals), www.flyfishinghistory.com/salt_water_fly_fishing.htm. Accessed 18 January 2012.

- Ken Cameron and Paul Schullery, “A New Early Date for American Fly Fishing,” The American Fly Fisher (Summer 2011, vol. 37, no. 3), 16; quote from Rodney Home letter, 1764, Accession #13918, Box W/5624, Special Collections/Marion du Pont Scott Sporting Collection, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Virginia.

- Jerome V. C. Smith, Natural History of the Fishes of Massachusetts (Boston: Allen & Tucknor, 1833).

- Cleveland Rockwell, “Pacific Salmon, 1876,” The American Fly Fisher (Spring 1980, vol. 7, no. 2), 9. This is a reprint of an article that first appeared in the Pacific Monthly in October 1903.

- Paul Schullery, American Fly Fishing: A History (New York: Nick Lyons Books, 1987), 155.

- James Henshall, Camping and Cruising in Florida, 1884 (Cincinnati, Ohio: R. Clarke & Co., 1884).

- Frank S. Pinckney, The Tarpon or “Silver King” (New York: The Angler’s Publishing Co., 1888), 66.

- A. W. Dimock, “Salt-Water Fly Fishing,” Country Life in America (25 January 1908), 303–06.

- Pinckney, The Tarpon or “Silver King,” 8.

- J. P. Wilson, “A Brief History of Silver Kings and the Anglers Who Stalk Them,” Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, www.tarbone.org/component/content/article/3-about-btt/12-tarpon-tales.html. Accessed 18 January 2012.

- “J. Q. A. Ward Ousts A. W. Dimock,” The New York Times (23 September 1894).

- “A. W. Dimock Dead: Financier-Author Sportsman Who Dominated Gold Market at 23 and Wrote Juvenile Books, Dies at Happy Valley,” The New York Times (13 September 1918).

- A. W. Dimock, “Saltwater Fly Fishing,” The American Fly Fisher (Summer 1979, vol. 6, no. 3), 6. This is a reprint of “Salt-Water Fly Fishing,” which appeared in the 25 January 1908 issue of Country Life in America.

- A. W. Dimock, The Book of the Tarpon (London: Frank Palmer, Red Lion Court, 1912), 246–48. This book was first published in New York in 1911 by the Outing Publishing Company.

- Julian Dimock, Outdoor Photography (New York, Outing Publishing Co., 1912), 33.

- A. W. Dimock, The Book of the Tarpon, 66.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid., 133.

- Ibid., 137.