By Jan Harold Brunvand

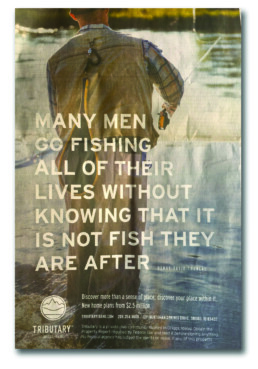

Late in the summer of 2020, a full-page advertisement in both Salt Lake City newspapers caught my eye. The bulk of the ad was a color photo of a lone fly fisher. Superimposed over the photo was this quotation: “Many men go fishing all of their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after. —Henry David Thoreau.” The fine print revealed that the ad was for an Idaho land development company. It continued, “Discover more than a sense of place; discover your place within it. New home plans from $2.5 million.”1

I thought it ironic to quote the guru of simple living in order to pitch expensive property, but a further irony is that Thoreau never wrote this. Jeffrey S. Cramer, in his compilation The Quotable Thoreau, identifies two versions of the saying in the “Misquotations and Misattributions” appendix of his book.2 For the purposes of the present investigation, I designate these as versions A and B:

A. Many men fish all their lives without ever realizing that it is not the fish they are after.

B. Many go fishing all their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after.

The newspaper advertisement cited above represents the B version with the addition of “men” (echoing version A) and “of.” Further examples of B, with minor variations, are widely quoted. For example, a book of Yellowstone fly patterns includes this: “Henry David Thoreau’s words [are] . . . ‘Many men go fishing all their lives without knowing that it is not the fish they are after!’”—adding “men,” “the,” and an exclamation point to B.3 Another example, the epigraph for the final chapter of a book on fishing lore, varies the B verbiage only by adding the words men and of.4

Cramer cites no misquotation source for B, but quotes A as follows from Michael Baughman’s A River Seen Right: “A lot of men fish all their lives without ever realizing that fish isn’t really what they’re after.”5 It should be noted that this is not word-for-word what Cramer gives as A. Another oddity is that the page reference cited (156) must be incorrect, because Baughman’s book has only 134 pages; the actual quotation appears on 68–69. I return to this source later, as it contains clues about how the misattribution may have developed.

Cramer is curator of collections of the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods, so it is not surprising that the same information appears on the institute’s website. Well, almost the same. The website’s misquotation page does not list the B version at all but has corrected the page reference for Baughman’s book.6 (Both Cramer’s book and the website mention a 1955 “parallel in a non-Thoreau text,” which I discuss below.)

There are scores of examples of this fishy quotation on the Internet, ranging from simply the words posted on lists of angling-related quotations to being printed on all sorts of artifacts, including posters, prints, and plaques with various backgrounds; a tapestry; a wall clock; a coffee mug; refrigerator magnets; and T-shirts (see the author’s photo on the Contributors page). Most of these have the same version B–ish wording, and none cites a source or date, so I focus here only on examples found in published books and articles in which context and dating may help to reveal the development of the misquotation.

It’s not that Thoreau never commented on fishing in his writings. Walden contains many passages about species of fish in the pond, methods of fishing, bait used, and even ice fishing. Thoreau expert Robert Sattelmeyer cited numerous passages concerning angling from Thoreau’s publications and journals in his article “‘The True Industry for Poets’: Fishing with Thoreau.”7 Sattelmeyer described Thoreau’s ambivalence concerning fishing, and he commented that “coupled with Thoreau’s recognition of the fisherman’s proverbial propensity for drink and dereliction . . . was a wish for some more favorable account of his kind.”8

Literary scholar and fly fisherman Willard P. Greenwood also reviewed Thoreau’s angling-related writings to identify the species of a big fish speared in Walden Pond as likely “one whopper of a brook trout.”9 There is no hint in either Sattelmeyer’s or Greenwood’s article of our fishy misquotation, nor is there in Mark Browning’s book-length study of fly fishing in North American literature.10 While Browning seems to downplay Thoreau’s influence on later fly-fishing writers, believing that “for Thoreau, there was nothing magical about fishing,”11 the title of one of his chapters echoes another famous Thoreau quotation: “How I Fished and What I Fished For.”12

Images one and two: The fishy quotation on refrigerator magnets, available in either white type on a black background or black on white. From a company listed online simply as Photomagnet on Amazon Marketplace. The author’s order arrived with the return address of a post office box in Trikala, Greece. Image three: A small sampling of results produced by a Google shopping search for “Thoreau quote fishing” performed on 8 March 2021.

If Thoreau never composed the fishy quotation, where did it come from? Cramer wrote that it “can be attributed to Michael Baughman’s A River Seen Right,” but it is not clear whether he meant that it should be thus attributed or merely can be.13 Cramer suggested that Baughman “may have been paraphrasing” a passage from Thoreau’s 1853 journal.14 There are three reasons to doubt this. First, Baughman himself did not originate the quotation, but quoted it from an angler he met on the river. Second, the journal passage is long and discursive, unlikely to have come to mind spontaneously while chatting streamside. Third, and most important, there is an earlier publication of pretty much the same misquotation. Here is how Joseph Wood Krutch phrased version A in his 1961 book: “Thoreau said that many men went fishing all their lives without ever realizing that fish was not what they were really looking for.”15 Note the slight variation here of concluding the statement with “really looking for.”

The passage in Baughman’s book where the fishy quotation occurs suggests how it may have originated. The context is that Baughman, “eighteen or twenty years ago,” watched “an elderly gentleman” seemingly miss hooking two nice steelhead. The older man explained that he had cut the points off his flies and was satisfied to be fishing “only for strikes.” The passage continues:

“Why did you decide to do that?” I asked him. “Because you don’t want to hurt the fish?”

“No, not that,” he answered. “I’ve read a lot of Thoreau.”

He looked at me and I nodded at him, to indicate that I’d read Thoreau too, and then he went on.

“I think it was in Walden where he wrote that a lot of men fish all their lives without ever realizing that fish isn’t really what they’re after. Well, a while back, I figured out that he was right, at least in my case. The fish are just a reasonable excuse to be out here. If I worry about them too much, I miss a lot of everything else—of what I’m really here for.” The old man smiled happily, “Does that make any sense?”

“Sure,” I said. “I remember that passage. I know what you mean.”16

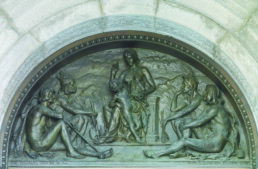

A bronze relief known as Tradition, created by Olin Levi Warner (1840–1896), sits above one of the main entrance doors of the Library of Congress’s Thomas Jefferson Building. In it, Tradition is represented as a storyteller, with her audience comprising (from left) a shepherd, a Viking, a child, an Indigenous American, and a prehistoric man—types of people the artist believed placed particular value on oral tradition. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-highsm-03146. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

What we have here is an instance of what folklorists call oral tradition—the transmission of ideas, stories, and wisdom person-to-person, face-to-face, by word of mouth, with the inevitable changes that this creates. By such a process, the realization that fishing is about more than just catching fish may have gradually become reduced to an aphorism—almost a proverb—about the supposed true purpose of going fishing. The saying sounded enough like Thoreau for people to believe that it was from Thoreau, with few, if any, actually checking the reference. People eventually accepted it, as Baughman did, as a genuine Thoreau quotation. Notice that the old fisherman said, “I think it was in Walden” (my emphasis).

Yet another occurrence of the misattribution, closer to version B, has a similar tone of assurance that the quotation is simply too well known to require any citation. In this instance, Robert DeMott wrote in the introduction to his anthology of essays by several fly fishers titled Astream, “I came to understand, in a way I never quite had before, Thoreau’s metaphysical proclamation in Walden that we fish all our lives without knowing that it isn’t fish we are really after.”17 (Could the “really after” here be an echo of Krutch’s “really looking for”?) DeMott had jotted a slightly different version of this quotation in his fishing journal for 22 August 2012, which was published in another of his books in 2016. This earlier version (although published later) reads, “More and more, I realize the truth of Thoreau’s proclamation that we fish all our lives without knowing that it isn’t fish we are really after.”18 The word “metaphysical” and the attribution to Walden came later (although published earlier). At no point, apparently, did DeMott or any of the contributors to Astream try to look it up in Thoreau, but why should they, since it was so obviously Thoreauvian in style and had been so widely quoted?

There are numerous examples of writers stating the general idea that fishing, especially fly fishing, is about more than just catching fish. Mark Browning even identifies a specific narrative genre consisting of “stories that suggest that many anglers miss the point of fishing, assuming that it has something do with the fish, when it really has everything to say about the anglers themselves.”19 Two such expressions of a similar idea show how such statements might have begun to approach the specific phraseology of the misquotation. In the introduction to a book on Midwestern fishing, we find the advice, “Don’t come to this country merely to catch fish. Take some time to get re-acquainted with the world around you. Slow down, look and listen. Even if you don’t catch anything, the change will do you good.”20 Coming a tad closer to the fishy Thoreau quotation, sportswriter Corey Ford put it like this: “Never ask a fisherman why he goes fishing, because he can’t tell you. How can he make you understand that it’s more than the fish he takes?”21

Jeffrey Cramer, remember, mentioned a 1955 “parallel in a non-Thoreau text.” How does that reference fit in? First, it’s definitely not Thoreauvian in style or specific reference. Author E. T. Brown, described on the book jacket as a political writer, hailed from Australia, and he only touched on fishing in an essay titled “On Gambling.”22 Brown’s point was that just as gamblers may claim that they need not win in order to enjoy gambling, fishermen may also insist that “they never really expected to catch anything. . . . When they go fishing, it is not really fish they are after. It is philosophic meditation.”23 (There’s that word “really” again.) Brown concluded that “the true end of fishing is fishing—if fishermen are to be believed.”24 It is tempting to view this passage as anticipating and perhaps even precipitating the fishy Thoreau quotation, but there are strong arguments against such an interpretation. The long paragraph in which the statement is buried is packed with details of a typical fisherman’s gear and unsuccessful quest for fish, and it seems highly unlikely that American readers could have spotted the similar sentiment expressed in a few sentences of a fairly obscure book from Down Under and turned it into a piece of fake Thoreau lore. Instead, I believe, we have here simply one more example of the common idea that fishermen are motivated by more than catching fish when they head to stream or lake.

There is, however, another observation by E. T. Brown that is pertinent. In the next paragraph, he declared, “The melancholy fact is that nobody believes fishermen. The almost universal opinion is that they would dearly like to catch fish.”25 So much for “philosophic meditation.” Fishermen are out to catch something. So it is, after all, really “fish they are after.” Few angling writers who quote the supposed Thoreau saying admit this universally acknowledged truth, but a significant one does: Michael Baughman. Following the passage in which he described the encounter onstream with the elderly gentleman who cut the points off his hooks, Baughman wrote, “I was fairly young, then, and I didn’t really quite believe in what he was trying to tell me. In fact, as soon as he’d left, I climbed down the bank to fish for the two steelhead he’d raised and was very happy to hook and land one of them.”26 The chapter concludes, however, that years later Baughman came to understand better what the old man meant, and now he values his experiences in nature as much as he does the actual catching of fish. Thus, he eventually applies the lesson that is so well expressed in the misquotation.

Back at the turn of the twentieth century in a book by Henry Van Dyke, we find a statement that combines the idea of what a fisherman may claim he is really pursuing (not fish, of course) with what most attracts him to the sport:

Never believe a fisherman when he tells you that he does not care about the fish he catches. He may say that he angles only for the pleasure of being out-of-doors, and that he is just as well contented when he takes nothing as when he makes a good catch. He may think so, but it is not true. He is not telling a deliberate falsehood. He is only assuming an unconscious pose, and indulging in a delicate bit of self-flattery.27

So the general idea of men fishing, or at least claiming to fish, for reasons other than actually catching fish, is common enough. But we are still left with the question of how this notion expressed in a memorable sentence came to be attributed to Thoreau.

To determine how, when, and by whom the famous-but-fake Thoreau quotation was created would require further dated examples of variations on the theme. Joseph Wood Krutch in 1961 was the earliest to quote it that I have found so far. Michael Baughman writing in 1995 remembered hearing the quotation eighteen or twenty years before, which would put it around 1975 to 1977. Baughman or any other fishing writer could have been quoting from Krutch’s The Forgotten Peninsula, a book that is still in print,28 or people could be quoting others who quoted Krutch. There’s a spread of years there from the 1960s to the 1980s from which I hope to find more examples.29 So, where did Krutch get the quotation? Was he paraphrasing something from Thoreau, or did he simply make it up? He certainly should have known Thoreau’s writings well, having published a biography of him in 1948.30 Sure enough, there is one passage in that book that seems to be leading up to the fishy quotation.

Most men, it seemed to him, had got the necessary introduction to nature as boys for they had hunted and fished. But few, for some reason, ever followed up on the acquaintance. They continued, he said scornfully, to suppose that the fish were themselves important. Even most Concorders might visit his sacred pond a thousand times “before the sediment of fishing would sink to the bottom and leave their purpose pure,—before they began to angle for the pond itself.”31

The passage in Walden that Krutch is alluding to here occurs in the chapter “Higher Laws.” He paraphrases the reference to men hunting and fishing as boys, and he quotes the “sediment of fishing” section but then skips several lines before picking up the “angle for the pond itself” section.32 Thus, even when supposedly quoting Thoreau, Krutch is handling the text rather freely. What is absolutely not found in this chapter or anywhere else in Walden is anything that Thoreau “said scornfully” about fish not being important. In fact, this section of Walden goes on to promote vegetarianism rather than to wax philosophic about fishing. Admittedly, the idea of men fishing for more than the fish themselves is implied in several places in Walden, but it is never phrased in the quotable succinct way that Krutch put it in his 1961 book. One must conclude—unlikely as it may seem—that a respected literary scholar seems to have invented an apt quotation where no actual example and attributable language was available. Whether this was the ultimate source of all versions of the fishy quotation remains to be proven.

In any case, the circulation of the fishy quotation continues. In a recent beautifully illustrated volume of thoughtful poetic essays on fly fishing, there it is again (version B): “Henry David Thoreau observes in Walden that, ‘Many go fishing all their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after.’”33 Nope, Thoreau never wrote anything quite this epigrammatic or insightful about the purpose of angling, no matter how many writers continue to assert that he did. What has been lacking all these years is fact-checking. Without that, we have chaos. John McPhee quoted a longtime New Yorker fact-checker, Sara Lippincott, who summed up what happens when an error once gets into print: “[It] will live on and on in libraries, carefully catalogued, scrupulously indexed . . . silicon-chipped, deceiving researcher after researcher down through the ages, all of whom will make new errors on the strength of the original errors, and so on and on into an exponential explosion of errata.”34

Appropriately enough, there is an authentic quotation from Walden that nicely sums up the situation. In the chapter “House Warming,” referring to the notion that old mortar on used bricks grows harder with age, Thoreau wrote, “[T]his is one of those sayings which men love to repeat whether they are true or not. Such sayings themselves grow harder and adhere more firmly with age, and it would take many blows with a trowel to clean an old wiseacre of them.”35

What might Thoreau have said to modern wiseacres who have provided him with such an apt quotation? Perhaps “I didn’t say that, but I should have.”

This article first appeared in the Winter 2022 (Vol. 48, No. 1) issue of the American Fly Fisher.

Endnotes

- The Salt Lake Tribune (5 September 2020), A7. The same ad ran several times in both the Tribune and the Deseret News, which at that time were sharing a printing plant and running the same advertising. As of January 2021, both papers ended this joint arrangement and ceased daily publication, instead providing online content and a weekly news magazine.

- Jeffrey S. Cramer, ed., The Quotable Thoreau (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2011), 466–67.

- Craig Mathews and John Juracek, Fly Patterns of Yellowstone, Volume Two (West Yellowstone, Mont.: Blue Ribbon Flies, 2008), 15.

- Eric Dregni, Let’s Go Fishing! Fish Tales from the North Woods (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 217.

- Cramer, The Quotable Thoreau, 467. The full reference to Baughman’s book is A River Seen Right: A Fly Fisherman’s North Umpqua (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1995).

- The Walden Woods Project, The Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods, “The Henry D. Thoreau Mis-Quotation Page,” www.walden.org/what-we-do/library/thoreau/mis-quotations/. Accessed 12 February 2021.

- Robert Sattelmeyer, “‘The True Industry for Poets’: Fishing with Thoreau,” ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture (vol. 33, no. 4, 1987), 188–201. I thank Professor Johanna Heloise Abtahi of Washington State University, managing editor of ESQ, for providing a copy of this article.

- Ibid., 191.

- Willard P. Greenwood, “Walden Pond’s Mystery Trout,” The American Fly Fisher (vol. 36, no. 4, Fall 2010), 12.

- Mark Browning, Haunted by Waters (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1998).

- Ibid., 53.

- Ibid., Chapter 8, 137–53.

- Cramer, The Quotable Thoreau, 466–67.

- Ibid., 467.

- Joseph Wood Krutch, The Forgotten Peninsula: A Naturalist in Baja California (New York: William Sloane Associates, 1961; Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1986), 33. This citation refers to the 1986 edition. I am indebted to Fred R. Shapiro, associate librarian for collections at the Yale University Law School, for this reference. Shapiro is editor of The Yale Book of Quotations. E-mail from Fred Shapiro to author, 7 October 2020.

- Baughman, A River Seen Right, 68–69.

- Robert DeMott, ed., Astream: American Writers on Fly Fishing (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012 [paperback edition 2014]), xxviii. Page reference is to the paperback edition.

- Robert DeMott, Angling Days: A Fly Fisher’s Journals (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016), 163.

- Browning, Haunted by Waters, 19.

- Shawn Perich, Fly-Fishing the North Country (Duluth, Minn.: Pfeifer-Hamilton Publishers, 1995), x.

- Laurie Morrow, ed.; Corey Ford, Trout Tales and Other Angling Stories (Bozeman, Mont.: Wilderness Adventures Press, 1995), 72. The date of this text is not specified; Ford was born in 1902 and died in 1969. Morrow was selecting material from the Corey Ford papers archived in the Dartmouth College Library.

- E. T. Brown, “On Gambling” (Chapter 29), Not Without Prejudice: Essays on Assorted Subjects (Melbourne: F. W. Cheshire, 1955), 139–43.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Baughman, A River Seen Right, 69.

- Henry Van Dyke, Fisherman’s Luck (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900), 25.

- The University of Arizona Press has the book for sale on its website, uapress.arizona.edu. Accessed 1 December 2020. Joseph Wood Krutch (1893–1970) was the author of many other books, articles, and reviews. He may well have repeated the fishy Thoreau quotation in another writing that I have not checked yet.

- Readers are invited to send references to jan.brunvand@gmail.com.

- Joseph Wood Krutch, Henry David Thoreau in the American Men of Letters Series (New York: William Sloane Associates, 1948; paperback edition New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1974). References are to the paperback edition.

- Ibid., 148.

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden, with an introduction and annotations by Bill McKibben (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004), 200. This is the edition I consulted while writing this piece.

- Robert Reid, Casting into Mystery (Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 2020), 111.

- John McPhee, Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017), 136.

- Thoreau, Walden, 226–27.