By John A. Feldenzer

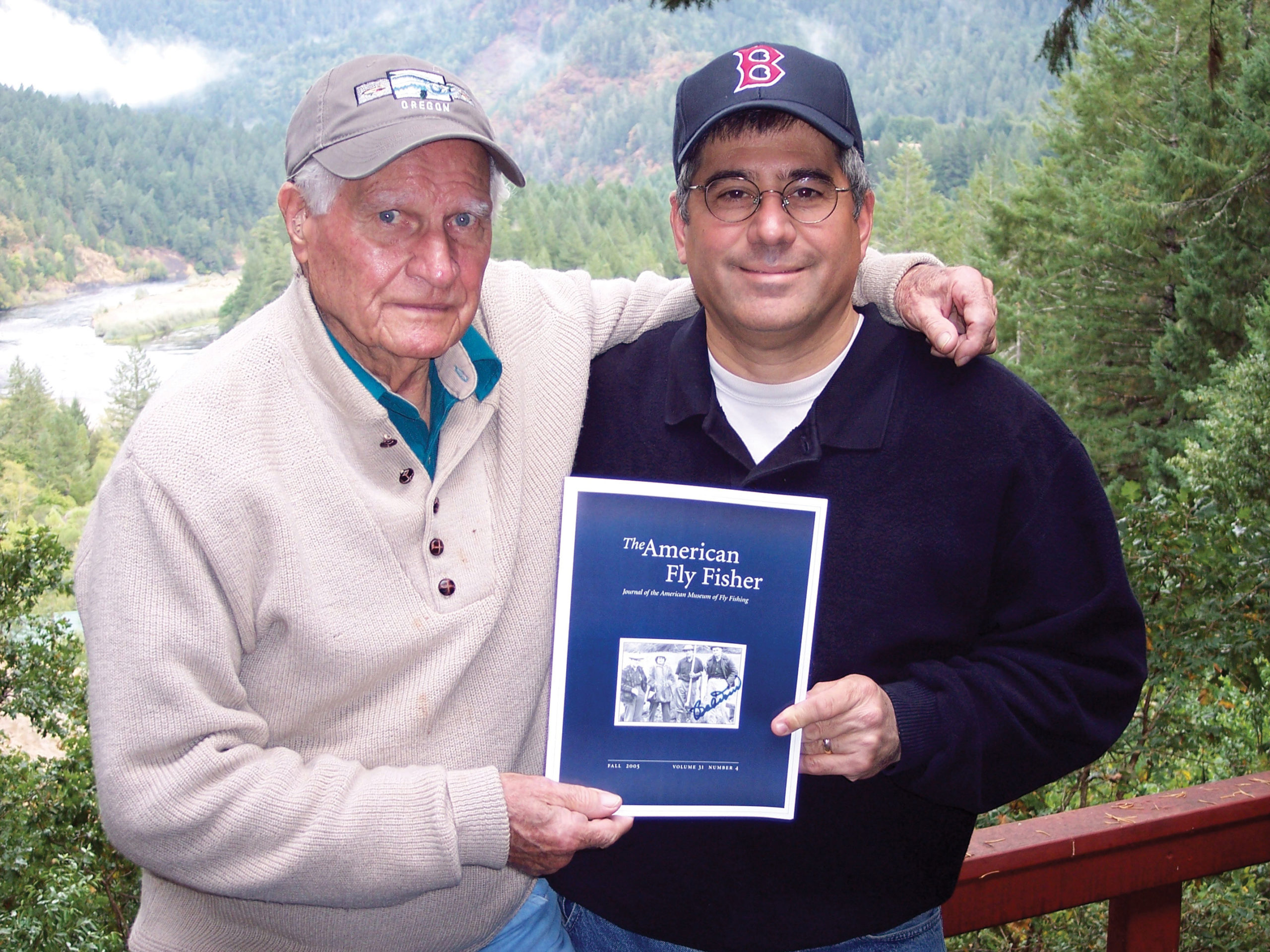

Bobby on his porch with the author and an autographed journal in October 2008. Photo by Karen C. Feldenzer.

It has been more than a dozen years since I chronicled the story of Boston Red Sox greats Bobby Doerr, Ted Williams, and their relationship with Paul Young and the fine bamboo rods that he produced and sold.1 On 7 April 2017, Bobby Doerr turned ninety-nine. When I began work on this article, I thought that it was time for an update before his one hundredth birthday; but my good friend Bobby Doerr died at 3:00 p.m. on 13 November 2017. This piece, in progress at the time of his death, is now a memorial.

An Unlikely Friendship

I met Robert Pershing Doerr in a convoluted way. A devoted collector and a student of fly-fishing-tackle history, I purchased a Paul Young “Bobby Doerr” model—a 9-foot, darkly flamed bamboo steelhead/salmon fly rod—from Martin Keane in 2004.2 Built originally in 1955 for Russell C. Malone of Matamoras, Pennsylvania, the rod (serial no. 2093) was in mint condition.3

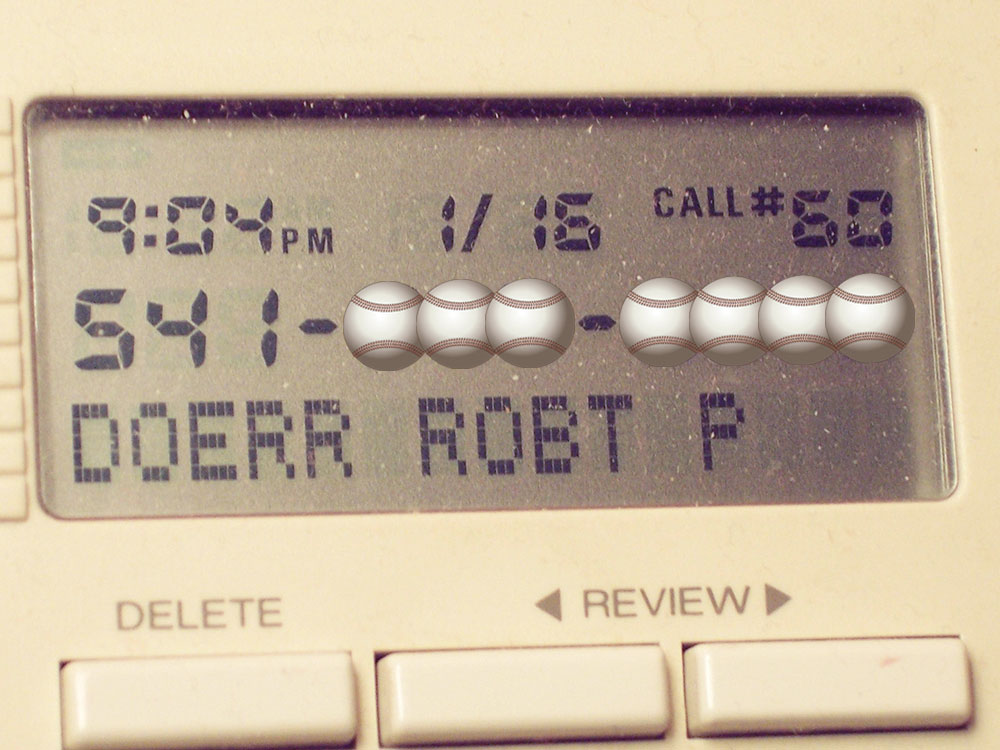

So who was Bobby Doerr? I grew up in central New Jersey as a Philadelphia Phillies fan and knew little to nothing about the Red Sox of old. Doerr had retired in 1951, four years before I was born. My father was an avid childhood Red Sox fan, but he had already passed. So I did what we now routinely do: I Googled him. An address in Junction City, Oregon, was available. I was reluctant to call him, so I wrote a letter and asked if he would call me to discuss the rod. (I had no idea then of the mail Bobby received daily from fans requesting autographs, etc.) Several weeks later came a message on the answering machine: “Hi John, this is Bob Doerr. I want to talk with you about that rod.” Thus began a friendship that lasted thirteen years. We discussed the rod and the failed attempt in 1990 by his friend Tom Ripp to publish the Doerr rod/Paul Young story in Fly Fisherman magazine; I then offered to investigate and document the story of Doerr, Williams, and Paul Young.4

The phone call. Bobby Doerr calls from the Rogue in January 2005 to discuss the Paul Young rod. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Bobby was very pleased with the 2005 article that appeared in the American Fly Fisher, “Of Baseball and Bamboo: Bobby Doerr, Ted Williams, and the Paul H. Young Rod Company.” He thought that it accurately reflected his relationship with Ted, the fishing on the Rogue, and their pursuit of fine tackle, particularly the functional, great-casting, well-made bamboo fly rods for use on river-run salmon and steelhead. Ted and Bobby’s friendship with Paul and Martha Marie Young, their memorable fishing trips on the Rogue River and in the Florida Keys, as well as their discussions with the innovative rod maker on taper improvement are an important part of fly-fishing history. Bobby was happy that his story had been told.

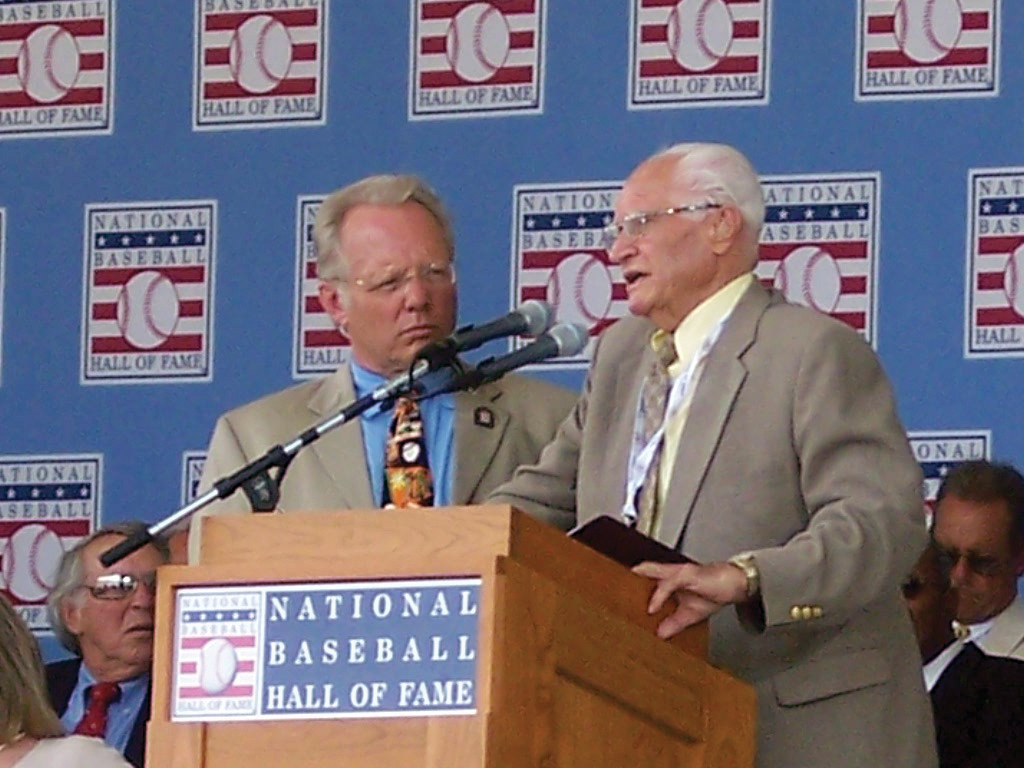

Beginning in 2005, my wife Karen and I became close friends of Doerr, then eighty-seven. He invited me to Red Sox training camp that year in Fort Myers and to a fund-raising dinner for the Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame in Hernando, Florida. There I met Dominic DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, and Dave “Boo” Ferris for the first time. We watched the Red Sox play the Cardinals. We were invited in 2007, as Bobby’s guests, to attend the Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony of Cal Ripken Jr. and Tony Gwynn at Cooperstown. On July 29, before the induction, the Hall of Fame honored Bobby Doerr in a special presentation. With time, however, our relationship focused more on fly fishing than Red Sox history. More accurately, it focused on fly fishing the Rogue River in Oregon for fall-run steelhead and salmon. In this article, I want to share some personal memories of fly fishing with this former Red Sox second baseman who, at the time of his death, was the Baseball Hall of Fame’s oldest living inductee.

Doerr’s Love of the Rogue (1936–2012)

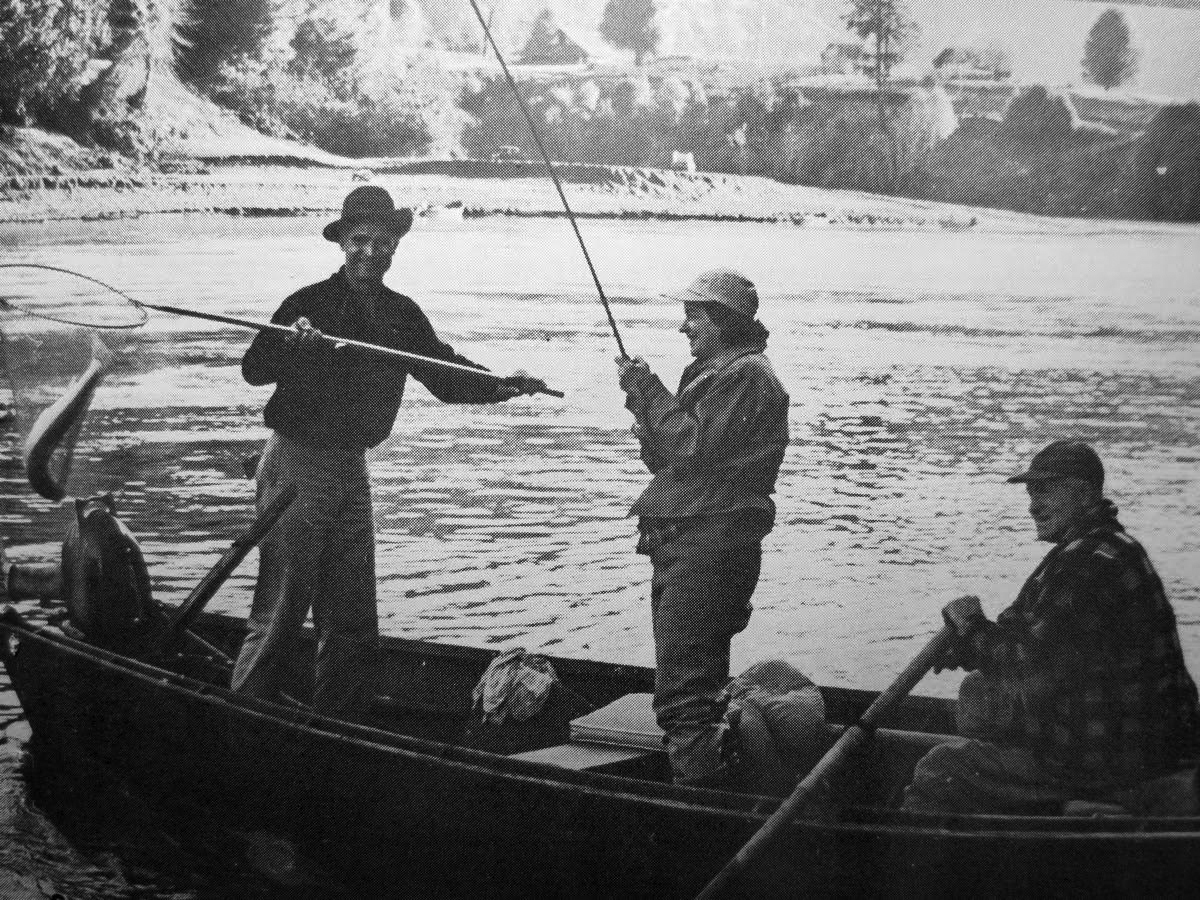

1958–59 Paul H. Young catalog photo (page 33): Bobby landing a steelhead on the Rogue River for Martha Marie Young. Image courtesy of Robert Golder.

Bobby fell in love with the Rogue as a teenager, and his knowledge of the river and its history was remarkable. He first came to the Illahe area of Agness on the Rogue in late 1936 with Les Cook to camp and fish.5 “Cookie” was an avid fisherman and the trainer for Bobby’s first team, the San Diego Padres (formerly the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League). There is a prominent rock in the middle of the river upstream of Doerr’s home (above Anderson’s Island and below Payton Riffle, across from Wild River Lodge) where Cookie placed the teenage Doerr and left him to fish there (in good water) most of the day! It’s called Cookie’s Rock, of course, among locals.

Bobby recognized the fishing and hunting opportunities and, when he signed with the Red Sox in 1937, he used his signing-bonus money to buy land on the Rogue. It was Les Cook who introduced Bobby to the local “little red-headed school teacher,” Monica Terpin, who later became his wife. In a video, Bobby Doerr: The Silent Captain, Bobby tells of their first date: a winter dance for which he had to cross the river to pick her up. She was dressed for the weather; he was not. On their way back to Monica’s home late in the night, the boat seat had iced up, and Bobby was unable to clear it. When he began to sit down, he noted that she had opened her overcoat for him to sit on. He said that he fell in love with her at that moment!6 They were married for sixty-five years. Their first home was a mountainside cabin built in 1938 by Burl Rutledge, a neighbor and owner of Illahe Lodge.7 Bobby lost his beloved “Mony” in December 2003.

Hall of Fame induction ceremony emcee Gary Thorne (left) and special honoree Bobby Doerr, 28 July 2007. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

At his retirement in 1951, Bobby was asked by Tom Yawkey, owner of the Red Sox, what he would like as a gift. Bobby asked for and received a well-needed generator, as there was no electricity then in that area of Agness. After retiring from the Red Sox, Doerr logged some of his Rogue property and worked as a fishing guide and mink farmer. He returned to the majors as a coach for the Red Sox (1967–1969), then the Toronto Blue Jays (1980). He kept his river home and always loved returning to the Rogue.

Bobby, Mony, and son Don lived on the mountainside until they moved to a ranch in Junction City, Mony’s hometown, so that Don could attend middle school in 1953. Bobby ran cattle on that ranch. The current Doerr ranch-style cabin was built on riverside high ground in 1960 by Bobby and his father. He kept this riverside home, usually staying there from fall through spring each year.

The Rogue River in southwest Oregon is one of the original eight wild and scenic rivers designated as such by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. It is famous for its beauty, teeming wildlife, and for camping, fishing, and white-water rafting. There is a rich riverine history, including early settlement, the Indian War of 1855–1856, and gold mining.8 Colorful characters abounded on the Rogue. It was a favorite destination for movie stars and sports figures. Zane Grey made its fishing famous in his 1928 book, Tales of Fresh-Water Fishing. It is no surprise that Doerr fell in love with this place.9

With Bobby on the Rogue (2005–2012)

View of the Rogue from Bobby’s house, September 2005. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

At Bobby’s invitation in 2005, Karen and I began our yearly fall excursions to southwestern Oregon. The drill was straightforward: we would fly across country, pick up Bobby, then drive the five hours in Bobby’s Chevy Suburban (complete with DOERR 1 license plates) to the Rogue. Our final destination was the lllahe area of Agness, about 35 miles upstream from the Rogue’s mouth at Gold Beach.

There is a spectacular view of the river from Bobby’s back porch. The home—adorned with a boat oar whose flat is labeled “Open Doerr”—is located next to the Illahe Lodge, where Ernie Rutledge, his parents, and now daughter Coleen have hosted and guided fishermen on the Rogue since the 1939–1940 season.10 We always planned on mid-September to early October for a week of fly fishing. This was the best time to catch the fall run of the Rogue’s famous so-called half-pounders. These 12- to 18-inch steelhead usually weigh more than a half pound and are a mixture of wild and stocked (identified by their clipped adipose fin) fish. They fight violently and often jump when hooked, as most anadromous fish will. We fished from a boat and were most successful with downstream swinging-nymph patterns, especially beadheads. Ernie’s Copper or Green Herniator patterns, popularized on the Trinity River, were favorites; 7-and 8-weight rods were most suitable, especially as an occasional salmon would be hooked. Occasionally, these half-pounders could be caught on the dry fly, such as a Royal Wulff.

Above: Illahe Lodge sign, September 2007. Below: “Open Doerr” sign at the cabin, September 2005. Photos by John A. Feldenzer.

In earlier years, Bobby would fire up his outboard, and we fished with him as guide. He had worked as a professional fishing guide on the Rogue after low-back problems forced his premature baseball retirement in 1951. Even in his late eighties, Bobby was a strong man with big, muscular arms, and he handled a boat well. Later, we secured the guiding services of Illahe Lodge’s Ernie Rutledge, his personal friend. Rarely would we use another guide. We usually fished upstream of Bobby’s house in the wild-river section. Bobby’s favorite holes included Brushy Bar Riffle, East Creek (the General’s Cabin), Solitude, Billings Ford, Clay Hill Pool, Payton Riffle, and Cookie’s Rock.11

Ernie Rutledge in September 2008. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Bobby was an excellent caster and very competent fly fisher even into his nineties. A typical day would have us on the river by 7:00 a.m., fish until 11:00 a.m., return at 4:00 p.m., and fish until dark. My fishing logs give the following data on steelhead I caught over a five-year period: 101 steelhead over four days in 2008, forty-five steelhead over four days in 2009, thirty-seven steelhead over three-and-a-half days in 2010, fifty-eight steelhead over three-and-a-half days in 2011, and seventy-four steelhead over three-and-a-half days in 2012, my last year on the Rogue. As mentioned before, these were a mixture of wild (25 to 35 percent) and hatchery fish. A large increase in the run of half-pounders occurred in 2008.12

Doerr was an icon on the river and well known among the locals. It was always a treat to go down to Cougar Lane (a tackle and grocery store, restaurant, campground, and motel!) for lunch or into Gold Beach to see Ted Watkins at Gold Beach Books and have dinner at Spinner’s Seafood, Steak & Chophouse. When Bobby was in town, word got out, and people came to meet him. Almost always an autograph or two was handed out.

Bobby guiding on the Rogue, September 2005. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Ernie guiding Bobby and the author in September 2008. Photo by Karen C. Feldenzer.

Bobby casting in September 2007. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Bobby and the author heading out for a day on the water in September 2008. Photo by Karen C. Feldenzer.

Bobby Doerr and Karen Feldenzer talking on the porch in September 2012. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Karen and Bobby usually started the day feeding corn to the wild turkeys, deer, and on one occasion, elk! The area was packed with wildlife. We often saw black bear on the banks of the Rogue, but they never approached the corn feeders at the house. When not fishing, we sat on the porch overlooking the river and talked. The stellar jays would screech and jump on and off the bird feeder while competing with Bruno, the local chipmunk, for seed. There were no cell phones or computer distractions. The TV was only on if the Red Sox were playing. It was perfect. We discussed topics from theology to politics; weather, especially historic local floods; Native American history; and arrowhead collecting. We talked about characters like the famous fishing guide Larry Lucas and the writer-fisherman Zane Grey. Grey’s Rogue River cabin is still intact at Winkle Bar.

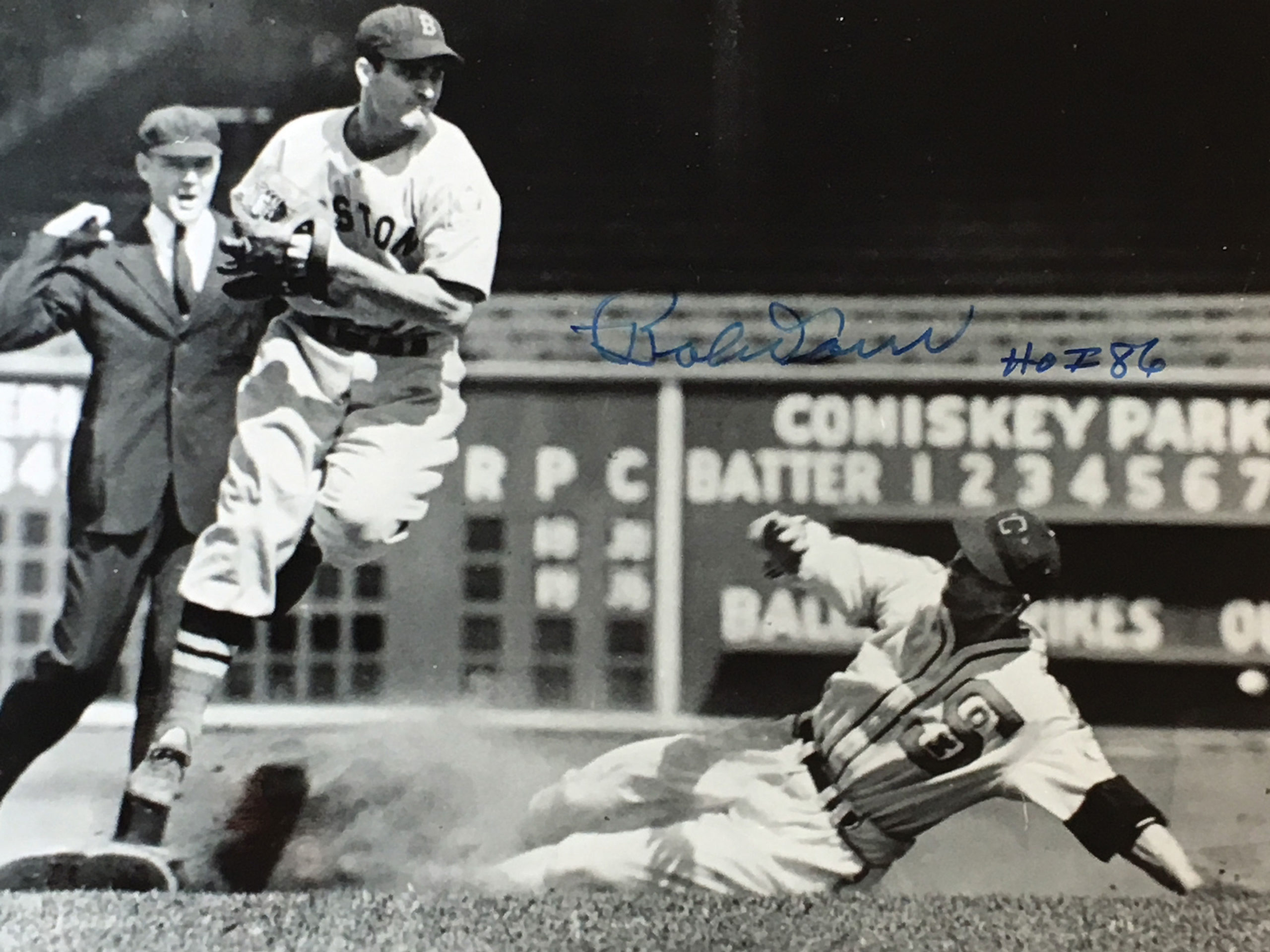

We also talked about baseball, America’s great pastime. As we had both played the keystone sack position (second base)—I as a collegiate athlete, he as a Hall of Fame major leaguer—our discussions were often technical: how to turn the double play, for example. We agreed that crossing the bag was optimal, but what about the footwork? Bobby was an excellent defensive second baseman, a top double-play man. He once handled 414 consecutive chances without an error.

Bobby Doerr turning a double play at Comiskey Park in the late 1930s/early 1940s. Umpire Ed Rummel makes the out call as Chicago White Sox first baseman Joe Kuhel slides into the bag. Photograph courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

I am a neurosurgeon. I asked Bobby about the spring of 1939 and Lou Gehrig. Doerr, then the twenty-one-year-old infielder, said that he and the Red Sox knew something was wrong with Lou in their season opener with the Yankees. Bobby watched as Gehrig struggled to run to first base. Yes, something was definitely wrong with the Iron Horse. On May 2, Gehrig pulled his name from the lineup in Detroit, ending his 2,130 consecutive-games record, beaten only by Cal Ripken Jr. On his thirty-sixth birthday (19 June 1939), Gehrig was diagnosed with the terminal neurological disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which now bears his name. He gave his famous, “Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth” speech on July 4 and died two years later.

Bobby told me the famous story of rookie Dom DiMaggio and his first Red Sox roommate, the veteran Moe Berg. Berg, who could speak a dozen languages fluently, read multiple newspapers (German, Japanese, Italian, Portuguese, and others) each day. He had them neatly organized in stacks: those to be read or those finished. DiMaggio, who was recovering from an ankle injury, was spending a lot of time in the room. Manager Joe Cronin came to visit. All of the furniture was covered with newspapers. Cronin moved the papers around and mixed some Greek papers with others as a practical joke. When DiMaggio returned that night after dinner, the room had been cleared of Berg’s belongings, including the newspapers. Berg’s note read: “Dominic, you’re much too popular and have too many visitors. My newspapers are too valuable to me.”13

Berg has the distinction of being the only major leaguer whose baseball card is on display at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.14 Berg, a catcher for the Red Sox, became a spy for the OSS during World War II.15 He was an excellent athlete and intellect. Thought to be the best baseball player in Princeton history, he played in the major leagues from 1923 to 1939. He obtained a law degree in the off-season.16 While on one of two baseball-related trips to Japan in the 1930s, Berg secretly photographed and took movies of key sites, such as the harbor and skyline of Tokyo. This information would prove valuable in creating the aerial maps for U.S. bombing missions years later. After Pearl Harbor, Berg fully embraced espionage and covertly assessed the Nazis’ atomic bomb capability deep in the Black Forest. In Switzerland, he had orders—if his participation in nuclear bomb creation could be confirmed—to assassinate Germany’s premier atomic physicist, Werner Heisenberg. Berg once impersonated a member of Berlin’s general staff on his “official inspection” of the secret Galileo munitions plant in Italy.17 Imagine: a Jewish man working behind Nazi lines as a spy!

We discussed the use of steroids in baseball. Bobby, like other athletes of his era, was most dismayed by the effect of these performance-enhancing drugs on the record book. There were already enough variables in the comparison of ballplayers over time: the dead-ball era, night games, plane travel, the increasing role of relief pitchers, improved equipment. No other sport pays more attention to the numbers than baseball, and now the numbers don’t mean much because of athletic performances corrupted by anabolic steroids.

In my 2005 article, I described the famous Rogue River debate between Bobby Doerr and Ted Williams on the proper way to swing a baseball bat. Bobby shared a privately made 1987 batting-clinic video with me, and it is something to see. Ted and Bobby, while fishing with friends, took a lunch break on the Rogue River’s bank.18 Then they argued, as if in court, their theories on how best to hit a baseball, complete with a baseball bat prop! Williams argued for the importance of hip rotation, a slight upswing, and “choking up” to increase bat speed. Doerr countered with his advice on a flat or level swing of the bat. Williams was in his typical form: aggressive, profane, and demeaning (in a humorous way) toward Bobby. Doerr was polite and firm, and failed to yield to the domineering Williams. The verdict of the fellow fishermen (the judges) on the bank: a tie!19

Besides discussions of baseball and fishing, one of our favorite activities with Bobby was “doing the mail.” We would walk the quarter mile up his unpaved driveway through a heavily wooded area (with a blow horn to “scare away cougars”), retrieve the box (yes, there was that much daily mail!), then sort through it. We would help Bobby with the balls, baseball cards, photographs, occasional bats, and requests to autograph or inscribe to fans. Then we packaged the returns and mailed them back. It was a daily event! We never tired of it. We never saw Bobby refuse an autograph or request of a fan. In fact, he carried extra Hall of Fame and baseball cards in his vehicle to sign and give away if necessary. A more kind, humble, and generous man we have not known in our lives.

Bobby signing baseballs at the cabin in September 2008. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

Several times a week, Bobby supervised the making and consuming of a Rogue River breakfast. This consisted of pan-fried steelhead fillets (yes, we were allowed to take a daily limit of stocked steelhead) and hotcakes with maple syrup. This may sound like an odd combination, but it was delicious. No fishing trip was complete without at least one. Although outwardly not religious, Bobby Doerr was a man of faith. His beliefs were privately held. He loved his God. He insisted on giving thanks before meals and reminded us to “say our prayers.” He enthusiastically participated in our occasional discussions of theology and enjoyed listening to preachers on audiotapes.

Karen helps Bobby prepare a Rogue River breakfast in September 2009. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

The Teammates Series of Graphite Rods

No article of mine about Bobby Doerr would be complete without a discussion of fishing tackle, and this is no exception. The story of the four legendary Red Sox teammates—Bobby Doerr, Dominic DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, and Ted Williams—was told by David Halberstam in 2003.20 It is a treat for die-hard baseball fans and a must-read for Red Sox Nation.

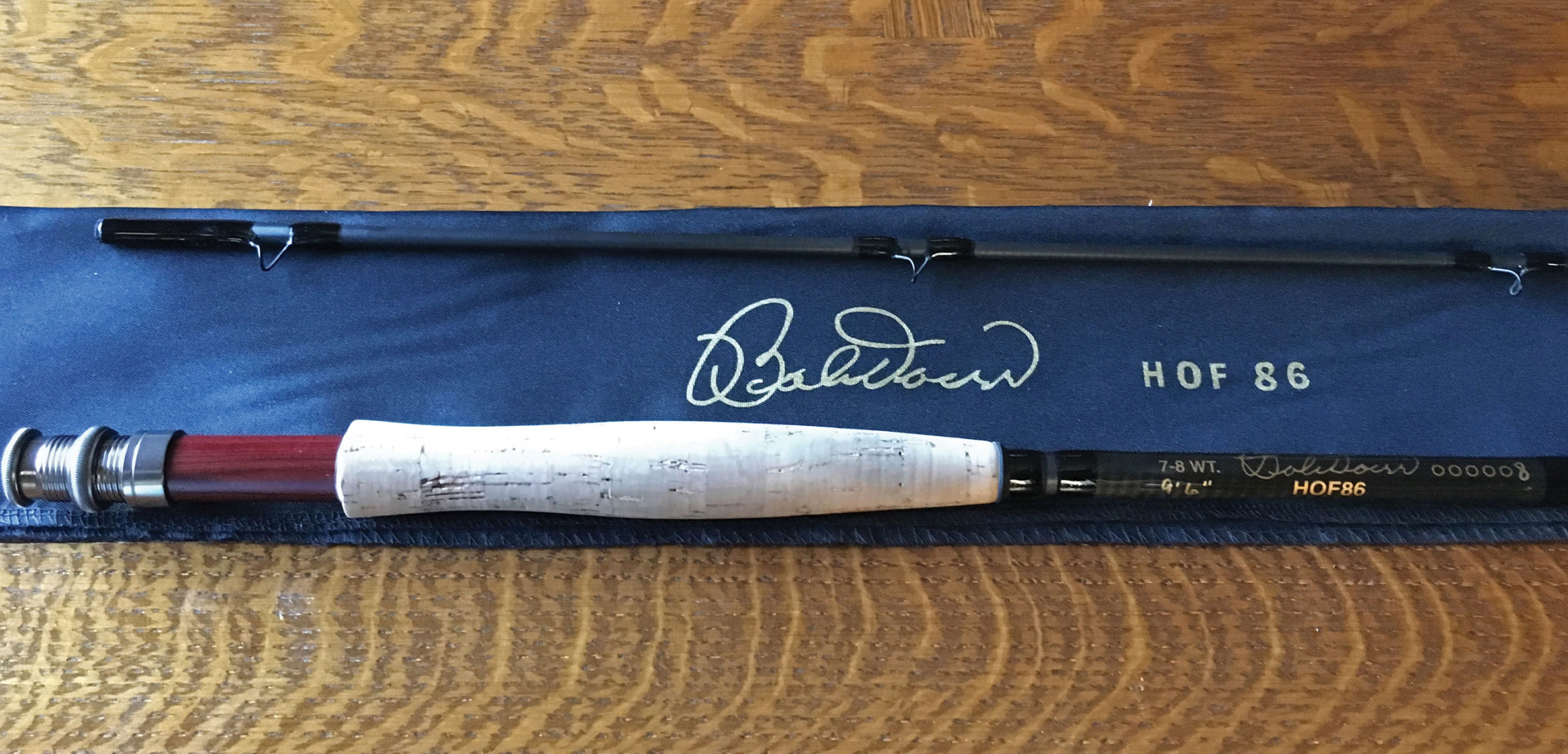

Bobby, along with a friend from Florida, Steve Brown, contracted rod builder Bud Erhardt from the Arkansas Ozarks to craft a series of graphite rods to honor the teammates.21 The prototype tapers were designed by Ted Williams back when he had his own tackle company (Ted Williams, Inc.) in the 1950s. The Doerr (9½-foot) and Williams (9-foot, 3-inch) models were two-piece, staggered-ferrule fly rods; DiMaggio’s was a bait caster22; and Pesky’s was a spinning rod.

Doerr and Williams rods, photographed by John A. Feldenzer in September 2007.

Bobby teaching casting at the Hall of Fame in May 2005. Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame; photograph by Mike Stewart.

Bobby loved casting and fishing the Ted Williams rod on the Rogue. He took it to Cooperstown once and gave a casting clinic there to interested children who competed in a contest to win a fly tied by Ted Williams. One of my favorite pictures of Bobby shows him that day instructing a young boy in the art of fly casting (at left). He made a gift of the Doerr model, serial #000008, to me. Bobby presented the #000002 Doerr rod to former President George H. W. Bush on a trip he made to Kennebunkport.23 The presentation is documented in The Silent Captain video. Bud Erhardt passed away in 2009.24

We often finished our trips by going out for Chinese food after returning to Junction City. Bobby’s sister, Dorothy Swancutt, enjoyed joining us.

The author’s Doerr rod, given to him by Bobby Doerr. Photo by John A. Feldenzer.

We were and remain thankful for each chance to see Bobby and spend time with this great man, a hero to us. As expected, time began to take its relentless toll on Bobby’s ability to get around. Travel became more difficult, and each year, the long trip from Junction City to the Rogue became increasingly unlikely. In 2012, for the first time, Bobby did not want to go out on the river to fish. He preferred to stay back at the house, sit on the porch, and reminisce with Karen. I realized then that fishing with Bobby Doerr had come to an end. It was our last trip to the Rogue.

On 13 November 2017, Karen and I lost our good friend Bobby Doerr in his one hundredth year on this earth.25 The Doerr family lost its patriarch. Red Sox Nation lost its “Silent Captain.” The Hall of Fame lost its oldest living member, and the baseball world lost one of its great players and ambassadors. I consider it a blessing and a privilege to have known Bobby Doerr and to have become his friend and fishing partner at the end of his ninth decade of life. I ended my 2005 article by saying, “Williams and Doerr were the heroes of our childhood and remain the objects of our fascination today.”26 It is still true.

A celebration of Bobby Doerr’s life was held on 13 January 2018 at the First Baptist Church of Eugene. Bobby’s longtime friend Tom Ripp shared stories. Great-nephew Craig Shugert offered a heartfelt, emotional eulogy, and Pastor Ted Slaeker reflected on Bobby’s Christian walk, beliefs, and outlook on life. At the end of the service, we all sang “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Then, at the reception, in personalized Bobby Doerr Red Sox caps, we ate hot dogs and Cracker Jack. It was perfect.

The author pays his respects to his departed friend at Bobby Doerr’s gravesite on 13 January 2018. Photo by Karen C. Feldenzer.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the help and friendship of Don Doerr, Bobby’s son, who corrected the draft and confirmed many facts. Thanks to Ernie Rutledge of Illahe Lodge for reading and reviewing historical events with me. We spent many great hours on the Rogue together. Lastly, I thank Karen, my wife of forty years, who shared these treasured moments with Bobby Doerr. She is responsible for capturing so many of those moments photographically. She is absolutely my favorite nonfishing person to go on a fishing trip with.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2018 (Vol. 44, No. 2) issue of the American Fly Fisher.

Endnotes

- John A. Feldenzer, “Of Baseball and Bamboo: Bobby Doerr, Ted Williams, and the Paul H. Young Rod Company,” The American Fly Fisher (Fall 2005, vol. 31, no. 4), 2–13.

- M. J. Keane, Classic Rods & Tackle, Inc., rod #57 (catalog #88, 2004), 9.

- Keane’s poetic catalog description of the Doerr rod: “[B]uilt by Paul Young himself with 2 different weight orig. tips one being 5.6 oz. for #7 line & the other format w/the heavier tip, where the rod weighs 5.73 oz. is for #8 line; this rod is extremely attractive in every way, has oxidized Super-Z ferrules & unique rich dk brown wraps w/a distinct burgundy tint, tungsten guides, fabulously darkly flamed exquisite shafts w/fine orig. varnish, 2×2 node placement, Wells grip w/perfect corks and cork SL seat, which has 95%–98% blk finish on fittings; sold by company on 10/31/1955—according to my orig. records, orig. owner’s name on shaft, size 17 ferrule. These rods are very scarce, this specimen appears 99% new unfished & has the most sophisticated of all the Young improvements in this one beautiful rod. $2000.”

- Feldenzer, “Of Baseball and Bamboo,” 12, note 64.

- Cougar Lane Lodge, in Agness, has an excellent collection of Rogue River wall photos from the 1930s and 1940s, including a picture of a young Bobby Doerr and Les Cook.

- Stephen Brown and Bobby Doerr, producers, Bobby Doerr: The Silent Captain (Daytona Beach, Fla.: Gabby Moblie Productions, 2007), running time 1:01:40.

- Ernie Rutledge, phone call with author, 9 December 2017.

- Kay Atwood, Illahe: The Story of Settlement in the Rogue River Canyon (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1978), 52, 199–200; and Matthew Leidecker, The Rogue River: A Comprehensive Guide from Prospect to Gold Beach (Hailey, Idaho: Idaho River Publications LLC, 2008), 72–73.

- Roger Dorband, The Rogue: Portrait of a River (Portland, Ore.: Raven Studios, 2006).

- For more information about the Illahe Lodge in Agness, Oregon, see http://illahelodge.com/.

- Leidecker, The Rogue River, 48. The General’s Cabin at East Creek was known as the Eagle’s Nest and was a fishing camp for retired World War II Army Air Force generals: Ira Eaker, Carl Spaatz, Fred Anderson, Nathan Twining, and Curtis LeMay. A small airstrip on the riverbank allowed access for these avid fishermen.

- Rogue River Seine Counts at Huntley Park by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife yield the following data: 2007: 17,574 total count of half-pounder steelhead (6,532 wild, 11,042 hatchery); 2008: 117,486 total count (28,349 wild, 89,137 hatchery); 2009: 68,680 total count (24,549 wild, 44,130 hatchery). Daniel Van Dyke, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, e-mail to author, 15 December 2017.

- Louis Kaufman, Barbara Fitzgerald, and Tom Sewell, Moe Berg: Athlete, Scholar, Spy (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974), 96; and Nicholas Davidoff, The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg (New York: Pantheon Books, 1994), 120.

- W. Thomas Smith Jr., Encyclopedia of the CIA (New York: Facts on File, 2003), 23.

- The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was formed during World War II and was the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

- In 1926, Berg failed to report to spring training with the Chicago White Sox, who had just bought his contract from the Reading Keys in the off season for approximately $50,000. Berg had quietly entered Columbia University Law School in 1925 and had to complete his first year before joining the team. In 1928, he received his law degree and was admitted to the New York State bar. He became an off-season attorney with the Wall Street firm of Satterlee and Canfield. Kaufman, Fitzgerald, and Sewell, Moe Berg, 59–61; and Central Intelligence Agency, News & Information, “A Look Back . . . Moe Berg: Baseball Player, Linguist, Lawyer, Intel Officer.” www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2007-featured-story-archive/moe-berg.html. Accessed 12 December 2017.

- Kaufman, Fitzgerald, and Sewell, Moe Berg, 25–28, 83–84, 172–74, 183, 191–211; and Davidoff, The Catcher Was a Spy, 187–88, 199–207.

- Feldenzer, “Of Baseball and Bamboo,” 9, note 81.

- Private video recording by Lee Thornally, Rogue River, 9 October 1987.

- David Halberstam, The Teammates: A Portrait of a Friendship (New York: Hyperion, 2003).

- Bud Erhardt Fishin Sticks is a trademark obtained by Bud Erhardt. Later, his rods were marketed as Fishin Edge rods. Bud was a charter member of the Fishing Hall of Fame and, for more than thirty years, a professional guide, designer, and developer of a wide variety of fishing rods. Bud Erhardt died in 2009. www.fishin-edge.com/proud-heritage.php. Accessed 29 November 2017.

- Feldenzer, “Of Baseball and Bamboo,” 13, figure 14.

- Bobby’s political opinions were—consistent with his quiet personality and humility—held close to the vest. He would open up in political discussions if he knew you well. He was conservative politically and, in the time that I knew him, a Republican, but not in an overt way as was Ted Williams.

- Approximately 1,235 individually numbered rods (the number 1,235 was chosen in recognition of the 1,235-pound blue marlin caught by Ted Williams in 1954) of the four types were built by Erhardt. Fifty of the Ted Williams 9-foot, 3-inch rods were auctioned (Lots 546 and 547) on 28 April 2012 by Hunt Auctions, LLC, Exton, Pennsylvania. www.huntauctions.com/live/view_lots_items_list_closed.cfm?auction=36&start_number =501&last_number=600. Accessed 13 December 2017.

- Mike Lupica, “The Graceful Life of Bobby Doerr,” Sports on Earth, 14 November 2017. www.sportsonearth.com/article/261868666/red-sox-legend-bobby-doerr-dies-ted-williams. Accessed 29 November 2017.

- Feldenzer, “Of Baseball and Bamboo,” 11.