By Graydon R. Hilyard

So, what’s a Dad to do?

There they are, your twelve-year-old son and his ten-year-old sister, their brightly beaming upturned faces pleading for “a really awesome fishing trip, Dad.”

Despite your ignoring the collected wisdom of doctors Spock, Ruth, and Phil and the religious right, the kids are okay. At least according to you. Their mother, she’s not so sure. Only reluctantly has she agreed to this fly-fishing business as one more hopeful brake on anything like their father’s youthful dalliance with adult beverages and drugs du jour. The joy at your young bride’s interest in your fly-tying bench and her enlightened questions concerning polar bear, jungle cock, and blue chatterer paled early on. Finding a canceled check made out to PETA will do that.

Admittedly, you are grateful that the offspring’s DNA was not breached at birth and that their IQs appear intact. Ironically, all of this good health and smarts creates its own set of problems. Not that you are complaining, mind you. It’s just that unless you are a well-heeled Republican or someone content on getting his rewards card punched in heaven, you got problems—namely, an orthodontist who needs a new garage for the three Mercedes, college tuition at $40,000-plus a year and rising, and a future wedding divorcing you from any pittance left over. No need for election-year politicians to fret about the Social Security system crashing. You are going to have to work until age seventy-five just to break even, which just so happens to be the life span of the average American male these days. How’s that for social engineering?

But back to the problem at hand: those beaming faces all decked out in waders and vests (no sheepskin patch, of course) pleading for “a really awesome fishing trip, Dad.”

Although Bogdans and bamboo retain their charm, thanks to the resumption of the China trade, you no longer have to miss house payments to outfit the kids. As to “a really awesome fishing trip,” that’s another matter. Maybe you came of age on a diet of Tap’s Tips and dreams of the Northwest Taxidermy School, but for these kids, after school to the local pond armed with a steel pole, bobber, and bent pin in search of a sunfish to stuff just will not do. Brought up on splashy catalogs and exotic journals requiring a passport just to subscribe, the damage has been done.

So, what’s a Dad to do?

Clearly, a plan is needed. Wait much longer, and boys and girls will be discovered and any parental influence will be on the wane. Soon, even a trip within the lower forty-eight may not do as Patagonia and Russian rivers seduce young dreamers oblivious to the falling dollar and rising price of Mideast oil. With today’s costs spiraling and tomorrow’s income plateauing, looking to bygone days, as we do while tracking Shang, may be your only direction left to go. (Nice segue, huh?)

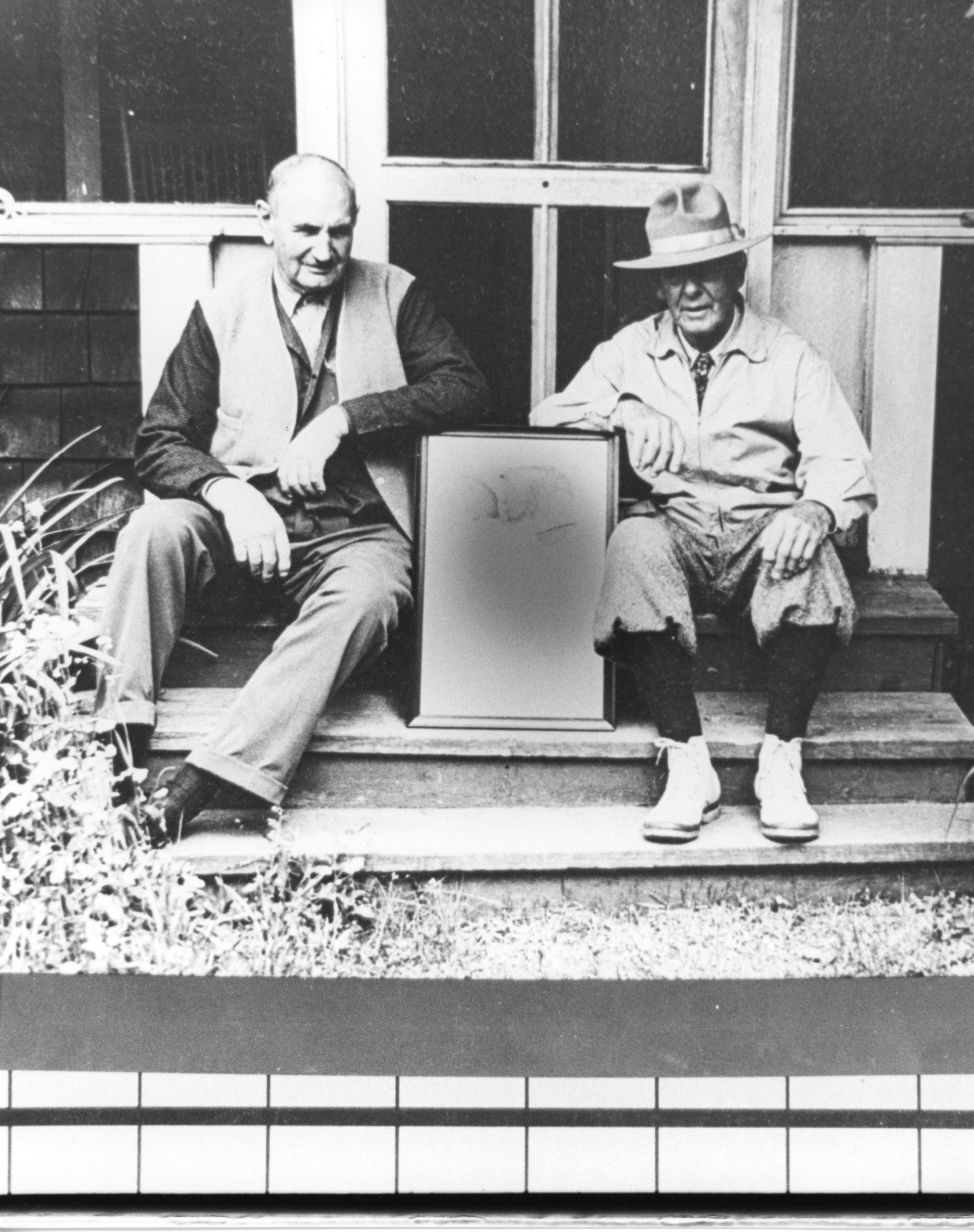

“Ode to Perley Flint”: camp humor at its best. From the collection of Charles McLaughlin.

Ode to Perley Flint

He got fish when others couldn’t

But tell the trick, he simply wouldn’t

He gets up early—so ’tis said,

While other anglers lie abed.

Of course this claim he just denies.

Another says “It’s in his wrist,”

With which he adds a special twist.

As most of us were still in doubt,

To get the truth—we set about.

We gathered at the camp one morn

A bit before the breakfast horn,

And looking north we saw a man

With shovel and tomato can,

Trip softly to the garden plot

And pick a soft and likely spot,

From which to dig some “garden hackle”

For use with modern fly-rod tackle.

We saw him grab a lusty worm,

We saw it wiggle, twist and squirm.

We saw him drop it in the can,

Then back to camp we quickly ran,

To call both guests and guides to see

This fisherman of mystery

Select the stock and tie the flies

Right there before our very eyes.

Most flies are made with greatest care

From feathers, silk and buck-tail hair,

But some that Perley Flint has made

Were made of worms, tin can and spade.

—“Shang”

May 1939

Unless your education has been sadly neglected, you already know that Charles Edward Wheeler (1872–1949), better known as Shang, was the premier waterfowl decoy carver working in the Stratford School tradition. Proof of past stature was his winning first prize in the amateur category of the International Decoy Makers Contest held annually at the National Sportsmen Show in New York City twelve years in a row, beginning in 1937.1 Proof of present stature is contemporary auction houses hammering down prices in excess of $75,000 per bird.2 Enough said.

What you may not know is that he was the absolute best fish carver of his day. There is good reason for not knowing. Until recently, only ten fish carvings were known to exist, all locked from view in private collections.3 As companion pieces to some of these rare carvings, Shang would compose rhymed verse of sorts, lampooning the fisher while casting the fish in the role of hero.

Neither were his pen-and-colored-ink drawings sometimes remarquing Christmas cards and correspondence too shabby either. Nor were his political cartoons drawn for the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Herald. Nor were his rare landscapes done in oil. Nor were his other minutiae, such as fishing flies, lures, and woven baskets in the form of creels. Shang wasn’t content to simply live the sporting life, either. Three tours of duty were spent in the Connecticut Senate and House of Representatives defending the environment that made it all possible.

All told, Shang’s life work output probably totals fewer than a thousand pieces, a fact not lost on collectors, particularly as decoy carving has become an important form of American folk art. However, economics were not in Shang’s equation. Every piece of carving, artwork, and ephemera was freely given away, with friendship the only price realized.

Of the few aware of Shang’s passion for sport, fewer still will know that two of his preferred sporting destinations were in the mountains of western Maine: Bosebuck Camps on Aziscohos Lake and nearby Upper Dam separating Mooselookmeguntic Lake from Upper Richardson Lake below. It is a little-known fact that each of these fisheries spawned a Shang fish carving, bringing the confirmed body count up to twelve. Both of these locales still offer quality brook trout and landlocked salmon in a wilderness setting at affordable prices. And, if they were good enough for Shang, they should be good enough for you.

So, here’s the plan, Dad.

First, you convince your Ivy League– prone wife that no normal kid ever learned anything in school during early June and September. Any rational teacher will tell you that. If that is not enough, explain to her that Aziscohos Lake is home to a Paleo-Indian site dating from the Paleo Indian Period‚ 11,000 to 9,000 B.P.4 Babble on about Ledge Ridge chert and fluted projectiles dating back to the sixth millennium. Let such talk flow glibly from your tongue. Surely, she will be impressed by your archaeological prowess and commitment to hands-on education. (No need to tell her that most of the Vail Site is now in the Maine State Museum at Augusta and the rest of it is under 20 feet of water.)

Next step is to persuade her that this would be the ideal time to visit her parents. Quality time and all that. Managing social arrangements is key here. No good ever came from an urban wife waiting back in camp staring back at the glassy-eyed deadheads on the wall while everyone else frolics in the forest primeval. All that under control, now you get to decide which it is going to be: Bosebuck Camps or Upper Dam. Unless you suffer from some undiagnosed form of mania, you do not want to combine these trips, although, given their proximity, it could be done.

Bosebuck lies near the hamlet of Wilson Mills, Maine, and is surrounded by 250,000 acres of pristine wilderness. It sits on the northwestern shore of Aziscohos, a lake created by dam building in 1911. In the 1920s, Shang would have arrived by steamboat from the foot of the lake. Today, you will arrive by 10 miles of dirt road marked by fields, forest, and the occasional out-of-control logging truck. Consider it part of the adventure.

Assuming the ruffed grouse (pronounced paaa-tridge in Maine) season is on and you can swear the kids to secrecy, you might revert to early behavior, as Bosebuck supplies both guns and dogs to hunt over.

Established in 1912 by Roland Ripley, son of the first Aziscohos dam keeper, Bosebuck consisted of only two camps until taken over by F. Perley Flint in 1919.5 Something of an entrepreneur, Flint rapidly expanded by convincing sportsmen to build their own camps at their expense on his donated land with his only profit coming from board and guiding.6 Eventually, he bought out all of the owners and assumed full control. Should you find yourself renting Shang’s camp, you will regret that recent insulation and interior walls now cover his notations and tracings of trophy fish. Then again, if it’s September, maybe you won’t.

Although Aziscohos Lake offers reasonable fishing and an opportunity to test young canoe skills, this is not why you are here. What Bosebuck really offers is miles of brook trout streams and guided access to the privately controlled Parmachenee watershed and the upper reaches of the Magalloway River. Not for nothing did President Eisenhower fish them both on his only trip to Maine in 1955, the event now marked by a bronze plaque at Little Boy Falls on the Magalloway. And, if it was good enough for Ike (you guessed it), it should be good enough for you.

Pattern Name: Aurora Borealis

Originated by: Shang Wheeler, circa 1945

Pattern source: Salmo Polaris carving

Hook: Number 4 sproat, blind eye, gut

Tail: A slip of white goose

Body: White chenille

Wing: Four ginger furnace hackles

Throat: Two silver badger tips dyed light blue

Head: Red

Aurora Borealis tied by Leslie K. Hilyard.

From the collection of Graydon R. Hilyard.

The main lodge was built in 1919 and housed, until he slipped into private collection, Salmo Polaris, a classic example of Shang’s fish carving and sense of humor. Carved in 1945, this 26-inch wooden salmon wears a coat of red fox, presumably to ward off the deathly chill brought on by the Aurora Borealis. No, not that aurora borealis—instead, a blind-eyed fly originated by Shang and found festooning the mouth of the deceased. Sensing resistance to the concept of a fur-bearing salmon, on the mount’s backboard Shang wisely provided a list of solemn witnesses attesting to the events of 11 May 1945.

Beguiled by Shang’s penchant for the tongue in cheek, this writer never questioned the fantasy nature of Salmo Polaris. But over time, the new owner wisely did, finding the blizzard reference on the backboard to be just a bit too specific. So, a meteorologic background check for the region ensued and‚ what do you know? On 11 May 1945, a massive blizzard roared out of the Berkshires in Massachusetts, then swept across Vermont and New Hampshire on its way to western Maine, leaving up to 26 inches of snow in its wake.7

Now, if you were Shang fishing the Magalloway on that day, just maybe, a fur-coated salmon was not really so far-fetched.

Though it offers fair value, should Bosebuck’s American Plan prove too costly, do not despair just yet, maxed-out Dad. Shang has a backup plan for you just down Route 16 east, a scant 5.5 miles from the Bosebuck entry sign. Do not bother to look for the entrance sign marking Upper Dam Road; the state long ago gave up supplying them to thieving fishers. Instead, consult your trip meter and take a right onto a dirt road, following it about 3 miles to a locked gate suggesting that you walk the final mile or so. You will know when you get there.

But first there is the practical matter of attending to lodging. Sadly, the Upper Dam House overlooking the Upper Dam Pool where Shang stayed was torn down in 1955 and its contents auctioned off. Instead, you will call Mooselookmeguntic Cabin Rentals in Oquossoc, who will fix you up in a century-old log cabin on the waterfront for a paltry $135 a night. For everybody. You bring the food; they supply everything else. With a little effort, you can convince your wife that you cannot afford to stay home. (And should you happen to rent this writer’s cabin, there is the added bonus of your defraying the cost of his writing this article gratis.)

All that in place, saddle up and retrace Route 16 west approximately 11.5 miles, turning left onto that unmarked dirt road that Shang would have traveled by buckboard. If you value your car’s suspension, you will arrive in about the same amount of time as that buckboard. Consider it part of the adventure. Granted, the ideal path from your camp to Upper Dam winds across 7 miles of sprawling Mooselookmeguntic, but that involves the considerable expense of a boat and guide. Then there are the additional problems of early morning fog, perpetual wind, and sudden storms. You may be content to hunker down and admire the century-old ambience, but your two kids will most assuredly not.

From time immemorial, until the combined effects of salmon and lake trout plantings collided, brook trout ruled at Upper Dam. Starting in 1842, with the arrival of fly fishers Crawford Allen, Phillip Allen, and Sullivan Dorr out of Providence, Rhode Island, fishers have flocked from the metropolitan East Coast and Europe to Upper Dam seduced by visions of 10- to 12-pound brook trout.8 In 1875, landlocked salmon became the hot new species, and everybody had to have them. So in they went with no hesitation, as no one realized how passive even large brook trout could be. Rather than misguided, the single lake trout planting in the 1950s was moronic. It seems that the pilot of the state stocking plane loaded with salmon for the Richardsons and lake trout for Moosehead got confused and pulled the wrong lever.9

During Shang’s heyday, large brook trout still lingered at Upper Dam, and he made frequent trips visiting his many friends, including Wallace and Carrie Stevens. Wallace was one of Maine’s premier guides whose prominence has since been eclipsed by his wife and her legendary Gray Ghost streamer. Originated circa 1934, L. L. Bean reports that it is still their best-selling streamer, followed closely by Herbie Welch’s Black Ghost, originated in 1927. But no matter the patterns used, nothing could seduce that wily mammoth brook trout named White Nose Pete, lurking beneath the sawmill at Upper Dam. Blessed with an atypical genetic code, he may still be in residence, as his capture has never been confirmed.

Not much choice, really, but for Shang to chisel out his most famous of all fish carvings, compose an ode eulogizing the failed Upper Dam elite, and present the tribute to Wallace Stevens. Lost for decades, White Nose Pete has recently surfaced and will rejoin the community upon the 2009 completion of the Rangeley Outdoor Sporting Heritage Museum in Oquossoc, Maine.

Everything that Shang touched smacks of museum quality, but White Nose Pete even more so. This is the only known example of a three-dimensional fish carving by Shang, and the only known example of a Carrie Stevens–tied Reverse-Tied Bucktail is among the many flies littering his kipe.

Unlike Flint’s 1945 Salmo Polaris, there is no firm origination date for Stevens’s White Nose Pete. However, the 1923 date on the White Nose Pete artwork dovetails with Carrie’s 1949 correspondence with Colonel Joseph D. Bates Jr., stating, “Mr. Wheeler did not come to the dam that year [1922] or in 1924—he was there in 1923.” And certainly, the rustic tying of the Reverse-Tied Bucktail found in the kipe is in keeping with her observed tying skills of the early 1920s. Additionally, we have the eyewitness account of Archer Poor, who saw White Nose Pete hanging in Camp Midway as early as 1933.10

Despite years of consistently unenlightened state fishery policies, good fishing prevails at Upper Dam. Your kids will have at least a chance at 3- to 5-pound brook trout without the cost of Labrador and an even better chance of a 3- to 6-pound landlocked salmon tail-walking across the pool. Brook trout purists will lament the landlocks, but not those who like their fish hyperkinetic. Admittedly, the chances of a 5-pound brook trout improve dramatically downstream, but that trip will cost you. And do not even think of trying to bushwhack in to the Rapid River from Route 16 with two small kids.

Fishing being fishing, the kids may very well not catch anything at all. But if fishing from the piers, they will at least see fish, as the salmon routinely hurl themselves up the sluiceways trying to reach Mooselookmeguntic Lake above. Kids tend to like that up-close-and-personal stuff.

About those piers: although they offer inexperienced anglers good fishing, with no trees to prune and turbulent water to work the streamer, they are extremely dangerous, particularly on frozen mornings. Lecture your kids and stay nearby. Water thundering past them at 500 cubic feet per second would seem to make the point, but with kids, you never know. (Probably best not to regard this as a photo op, as your next wifely contact will be in the form of a restraining order.) Wading the edges of the pool is somewhat safer, but the bottom tends to fall out quickly at times. Hanging on the dam catwalk is a battered float ring, reminiscent of the Titanic, that is probably not going to do much good.

As for you, don’t even think of “borrowing” one of those boats pulled up on shore. They belong to well-trained campers who have grown up on the pool and require no locks for good reasons. Surviving the conflicting crosscurrents and whirlpools is beyond your scope. Do not feel bad, as even area guides are reluctant to shove off into such chaos.

Come noontime, a shore lunch with the kids. Then a walk down the Carry Road leading to the Upper Richardson, passing by Camp Midway, once the home of Carrie Stevens. Pause there a moment and have the kids read aloud from the plaque memorializing her and her Gray Ghost. Tell them how she originated at least ninety-two streamer patterns, naming some after close friends such as G. Donald and Theresa Bartlett and Ben and Ruth Pearson, husbands and wives who faithfully fished Upper Dam. Tell them that later on today, they will visit the local fly shop, and they can buy a Gray Ghost and some patterns named after Shang. Tell them that tomorrow their luck will definitely improve. Instill hope. Do this, and you will have given your children a gift beyond price.

Acknowledgment

Additional thanks are due to John Monahan of Dedham, Massachusetts, for his consummate research skills.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2009 (Vol. 35, No. 4) issue of the American Fly Fisher.

Endnotes

- Graydon R. Hilyard and Leslie K. Hilyard, Carrie Stevens: Maker of Rangeley Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2000), 7.

- Because of space limitations, this article does not include a table listing Shang Wheeler auction prices for decoys (1991–2007). Prices ranged from a pintail sold in 1995 for $1,000 to a standing gull sold in 2005 for $80,000. Per Jamie Sayers of Guyette & Schmidt, Saint Michaels, Maryland, the nation’s leading decoy auction house: “Since our founding in 1984, we have auctioned approximately ninety-six Shang Wheeler birds, but only one fish carving: White Nose Pete in 1995 for $10,750 plus buyer’s premium” (interview with author, August 2008).

- Dixon MacD. Merkt and Mark H. Lytle, Shang (Spanish Fork, Utah: Hillcrest Publications, 1984), 103.

- Bruce J. Bourque, Steven L. Cox, and Ruth Holmes Whitehead, Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 22–27.

- Edward Ellis, Chronological History of the Rangeley Lakes Region (Travose, Pa.: Brook Trout Press, 1983), 60.

- Tom Rideout (early owner of Bosebuck Camps), interview with author, February 2007.

- David McWilliams Ludlum, The Country Journal New England Weather Book (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976), 21.

- Zenas T. Haines, Rangeley Lakes (newspaper), 1895 (vol. 2, no. 45).

- Archer Poor Jr. (manager of Camp Bellevue, Upper Richardson Lake), interview with author, 26 September 1995.

- Hilyard and Hilyard, Carrie Stevens, 25.