by Alexander Benoît

The first map I made was of my grandfather’s garden, which I kept crumpled in my pocket. If he asked me to pick a rutabaga for dinner, I’d pull out my map and run into the garden to search for one. For suburban New Britain, his garden was rather large—maybe 20 yards wide by 60 yards long. Here, he and his wife, Florence, were able to recreate the culinary delicacies of Old World Poland and integrate them into New World New Britain, with meals such as gołąbki (gu-wum-ki) and borscht. Their garden and their food told a story that is one part immigrant narrative and one part treatise on nature: work hard, work with the land and space you are given, and you will survive.

I was young when I realized that every map tells, at best, a partial story. My map of the garden didn’t capture what I felt when I walked into the house my grandfather built, or how I remember sticky August afternoons in the garden, picking raspberries. I learned these experiences evaporated quickly if I didn’t somehow record them, and I became captivated with how places were remembered. How was I, or anyone, to convey attachment to landscape?

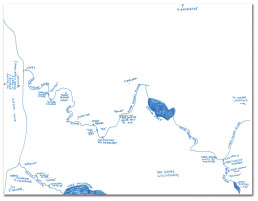

Everyone has a fish story; I tell mine through maps. They are informal and, more often than not, scaled to a dimension that only Lewis Carroll’s Alice would appreciate. When I draw maps of places I am tethered to, like Lewis Creek, some spaces are more distorted than others. Some areas are compressed while some are expanded exponentially. In my map of Lewis Creek, for instance, there is no sense of scale; to anyone besides me, this sketch is useless.

Lewis Creek map, 5 June 2017.

I grew up around various forms of maps, both imagined and tangible. My grandfather had visited Alaska in the late 1980s to celebrate his retirement. Over homemade strawberry-rhubarb pie and ice cream, he’d tell me about the Inside Passage, Mount Saint Elias, and the hordes of salmon he never fished for—his wife didn’t care for the blood and guts, preferring the root vegetables and leafy greens of their suburban garden. I’d lay awake at night in their house, walking through the mental landscapes he had planted in my mind, pining for the solitude of a glacial river I’d never known.

In the ensuing fifteen years, my cartographic impulse was fueled by the north woods of Maine. While fishing with my dad and grandfather, I’d create maps of places I fished. In my map of the Kennebec River, I marked fishing holes where landlocked Atlantic salmon and brook trout stacked up when the water was low, or where my cousin fell in and filled his waders one Memorial Day weekend. These markings created what I now know as a deep map, a type of map that strives to capture elements beyond what is two-dimensional. Usually deep maps are created with modern GIS tools to create a layered appearance; I used just pen and paper. Inspired by the literary deep-mapping projects of William Least Heat-Moon and Tim Robinson, I strove to capture not just the moments of revelation or epiphany on the river—of which there are, admittedly, few—but also the ordinary.

My grandfather is now in his mid-nineties. Like other nonagenarians, he has his good days and his bad days. He’s losing his memory slowly; he doesn’t remember Alaska anymore, and there are days he forgets that he was married for nearly seventy years. When I visit him in his nursing home in Rhode Island, I wheel him down the hall to the fish tank filled with African cichlids and pictus catfish. We sit for an hour and talk. I tell him about my own trip to Alaska, and I show him photos and the maps I made so he can feel how I felt two decades ago when he shared his story with me.

In the summer of 2018 I was armed with not just rods and flies, but notebooks and pens. I was not alone on my journey to Alaska; my father, his friend Steve, and Steve’s son Christian joined me. Christian and I were greenhorns; we had never set foot on the West Coast, and our understanding of Alaska was limited to reading Jack London and watching Brother Bear. I figured I had to map these places I was going to, if only to counteract being overwhelmed. More than anything, I wanted to remember—experiences like this often go unrecorded, and details that seem memorable at the time vanish in a matter of months.

My maps of Alaska look more like distortions of reality than anything else. They seemed more appropriate in a landscape where it was necessary to warp reality in order to put it to paper. Like Borges’s Ireneo Funes, I struggled to capture the spirit and memory of the place and to create maps that held personal meaning. I was trying to understand the gaps between the realities that maps display and the ones we live in.

An hour into the drive from Anchorage to Soldotna, I looked down for the first time. In the seat-back pocket was a DeLorme Atlas & Gazetteer of Alaska. When we stopped for dinner at a joint on Turnagain Arm that sold salmon pizza, I pulled it out and scanned for where we were. Instead of being preoccupied with the mountains that wreathed the Arm, I was drawn to nearby rivers, and three in particular: the Lake Fork Crescent, the Kenai, and the Russian. These three are the holy trinity of salmon fishing in south-central Alaska.

Our first day fishing was spent on the Lake Crescent Fork, catching sockeye and avoiding grizzlies. That night, as I cooked some of the sockeye salmon for dinner, I drew in the notebook I had been keeping in a ziplock bag in the pocket of my waders. I drew the river as a straight line from Crescent Lake to the Cook Inlet, forgetting all of the stories and details I had pledged to remember. I had forgotten, and it was only day one.

Mountains on the western side of Cook Inlet, near Lake Crescent Fork River. Photograph by Alexander Benoît.

“Badger” (real name unknown) filleting sockeye salmon in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Photograph by Alexander Benoît.

In my defense, I was preoccupied by the color of the salmon I was cooking. Sockeye salmon flesh is a shade of impossible vermilion, a color so pure and definite that I couldn’t match it with the palette in my head. A year later, as I read Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, I was drawn to her opening line: “Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color.” Nelson’s words described an infatuation so basic that it shocked me with its simplicity: I had fallen in love with vermilion.

I spent the next six evenings reclining on the porch of our cabin reading and drawing crude approximations of where we’d been that day. I tried to absorb not only the physical topography, but also the stories I heard along the way. Deciding what stories and figures to include was beyond difficult; if you include one story but not the other, you end up erasing one from your memory and immortalizing another. I thought of Jack London, who testified, “Keep a notebook. Travel with it, eat with it, sleep with it. Slap into it every stray thought that flutters up into your brain. Cheap paper is less perishable than gray matter, and lead pencil markings endure longer than memory.”

When I closed my notebook that night, the sun had just set; it was 10:30 p.m. I thought of London as I was falling asleep, and I thought I heard a bear in the distance.

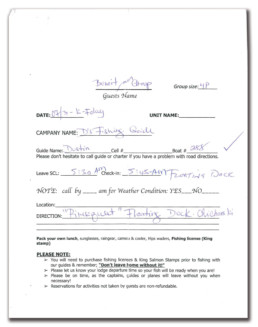

Hand-drawn map of Kenai River.

We learned we’d be fishing with Dustin the night before, as we did with all of our guides. Each day at 9:00 p.m., a sheet of paper with a map was tacked onto a bulletin board outside our cabin door. The reverse side noted our guide’s name, what time we were to meet, and where. We would be met on the Lower Kenai at 5:45 a.m. the next day.

A former state crappie and walleye champion from Illinois, Dustin caught the same Alaskan bug that drove John McPhee to write Coming into the Country. Dustin sported a mullet like Kenny Powers and had a handlebar mustache that I would have been comfortable holding onto in class IV white-water rapids. He was in his mid-twenties and supported his family by fishing during the short summers and leading hunting trips for moose and bear on Kodiak Island during the winter.

In the breast pocket of his canvas overshirt, which was stained with roe, mud, and blood, he kept a notebook that held his own hand-drawn maps of the bends and eddies of the Kenai, where resting salmon were likely to stack up before moving upriver to their spawning redds. Different species would congregate in different parts of the river, and at different times as well. In between spitting rockets of tobacco juice into the river, Dustin noted that notebook-keeping was common practice among the guides. Each of them came to give their own names to their favorite troughs and runs. It was crucial to update these maps on a tidal river like the Kenai, which changed not only year to year, but between tidal cycles. McPhee echoes this, too: “A stream course in Alaska, writhing like a firehose, can rapidly put a map out of date.”

With Dustin at the helm of his aluminum craft, we fished for pink and coho salmon. I’d forgive you if you couldn’t tell the difference between them, but if you hook into a coho and a pink, you’ll immediately be able to tell one from the other. A coho will make you feel like a 90-pound high school freshman being body-slammed by a senior who plays defensive line. Pinks, by comparison, will make you feel like you are doing curls with 2-pound weights. Cohos are prized for their rich, fatty fillets sold to restaurants and grocers in New York and Chicago. Pinks will be smoked or canned by locals and discarded like offal by New Yorkers.

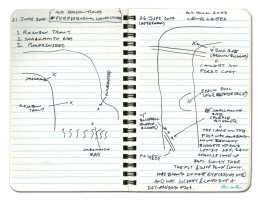

Pages in my notebook detailing catches from 7/30/18 and 7/31/18.

We limited out on pinks by 8:00 and went to Dustin’s dock to clean them. Pinks run in Alaskan rivers on even years only, and while I felt privileged to check another species off my bucket list, Dustin and the others treated them more as a nuisance—their sheer numbers in the river were preventing anglers from catching other, more desirable species. As Dustin filleted the fish, I took out my notebook and began to sketch where we’d been on the river. As I looked down into the water from the dock, I noticed a conglomerate mass sitting on the river bottom, rolling slowly like a tumbleweed with the current.

This is something you don’t see on a satellite image of the Kenai—the hordes of decaying and drifting salmon carcasses. This half-eaten, filleted, discarded carrion flows past you as you stand waist-deep in glacial flow or look over the side of your Mackenzie boat. Maps typically do injustice to this mass death, and it’s difficult for us to understand it in human terms except in comparison to the bubonic plague, the 1918 Spanish flu, or smallpox. Even this comparison is insufficient. In rivers all around the Pacific Rim where salmon run, this mass death happens every year, not to just one but to four to five species of salmon (this is unique to Pacific salmonids, which die soon after they spawn). We’re talking about numbers in the millions. There isn’t a more concrete and sobering example of the death drive than salmon, especially the king of kings.

The Chinook, or king, salmon is the largest of the family Salmonidae and the one most prized by anglers. You can easily pick them out in the river—their size alone prevents you from mistaking them for another. If they accidentally swim into you as you stand in the water fishing for them, you’d think a tree that had fallen into the water upstream had rammed into you. While other rivers in Alaska and the northern Pacific seaboard have larger Chinook runs, the Kenai harbors some of largest Chinooks in the world, including the record 97-pound one caught by Les Anderson in 1985. They are the lifeblood of the Kenai Peninsula’s ecology and genius loci.

My first Chinook was a love affair. After forty-five minutes, I brought it to net, and Dustin calmly netted it. I knelt down and grabbed its tail and cradled it for a moment. I fell in love with its color, a palette running from chrome to red. This hen was recently in from the sea; Dustin pointed out the sea lice behind the gill plates. It had probably entered on the previous high tide. We had been told earlier that there was a moratorium on keeping any Chinook caught on the Kenai, so it had to be returned to the river.

After letting it slowly slip back into the current, I thought of how it would soon die the same death millions of other salmon were dying that summer. That night, the memory of my previous hours kept me up as the others slept, and so I sat on the cabin floor looking at the gazetteer that I’d taken from the car. I thought to myself, how are you supposed to capture this death on a map? Do you shade in areas that have a higher quantity of the dead, or do you account for the raised height of the riverbed as the carcasses collect? Can you do anything at all?

Map of Kenai River from 31 July 2018, with accompanying celebratory beer label.

When we left three days later, my map of that day was incomplete, and it still is. Though I had journaled about catching my Chinook, I hadn’t found a way to figure this fish’s life into my map. I tipped my sun-bleached hat over my eyes in the airport terminal, and my mind drifted back to my grandfather’s garden and his Alaskan tales. He doesn’t remember much about living in New Britain and having a garden, but when I show him the map I made more than a decade ago, he starts talking about how the neighbor kept cutting down his raspberry bushes on their shared fence. Odds are that he won’t remember this trip after I tell him the first time, but I can leave him my maps and he can retrace my steps and feel what I felt as I held the 54-pound Chinook in my quivering hands.

I got on the plane and reached into my pen case and pulled a black pen out halfway before dropping it and grabbing for a blue one. I thought for a while, looking out the window at Mount Saint Elias. I began to sketch the blue lines showing the migration of my Chinook across the Pacific to where we met, and I put a small vermilion dot on that spot. Maggie Nelson brought me back to this map a year later, describing my precise cartographic impulse: “I am writing all this down in blue ink, so as to remember that all words, not just some, are written in water.”

By the time we touched down in Boston, I was content with remembering the Kenai and this Chinook imperfectly. Because when this landscape is gone and the salmon no longer swim upstream, someone must remember.

Alexander Benoît is a writer and educator living in North Carolina. He was born and grew up in New England, where his father and grandfather taught him to fly fish from an early age. These early fishing trips kindled his love for salmon and trout. While he attended the University of Vermont, he fished for trout, pike, musky, and bass, before moving to Boston to complete his master’s degree in Irish literature and culture at Boston College. He currently teaches middle and high school English and writing in North Carolina, and in the summer he fishes Minnesota’s north woods for pike and musky.