by John Mundt, Jr.

...This momentous and noble decision, in which the hearts of the immense majority of Americans are with the President, there are undoubtedly many strong and righteous reasons. ..But we must never forget that the specific reason given by the President, the definite cause which forced us into the war . . . which he has repeatedly denounced as illegal, immoral, inhuman-a direct and brutal attack upon us and all mankind. These words cannot be forgotten, nor is it likely the President will retract them.

They set up at least one steadfast mark in the midst of the present flood of peace talk. There can be no parlay with a criminal who is in the full and exultant practice of his crime. ..an honorable peace is unattainable except by fighting for it and winning it.1

Reading these grave words evoked in me a lucid image of United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in a well-tailored Brooks Brothers suit addressing the White House press corps about America’s ongoing war on terror. An all-too-familiar image of the troubled times we live in quickly spirited away when I realized that the words came from the book in my hands, written by the esteemed angling statesman Henry van Dyke in the year 1917; the volume was produced at a time when our world was burdened by the most wide-scale war ever waged. There are stark similarities between the catastrophic events of that era and our own terror-laden world.

At first glance, it might appear that the ancient arts of angling and war would be wholly incompatible, with the former historically being practiced under calm and peace-filled skies. Ironically, the historic record cites numerous accounts of brave men who assumed great risks in pursuit of the sport they loved while trapped in the throes of bloody conflict.

Statesmen, tournament casters, and others chose to fish as well as fight.

STORM CLOUDS

The Red Flower

June 1914

In the pleasant time of Pentecost,

By the little river Kyll,

I followed the angler’s winding path

Or waded the stream at will,

And the friendly fertile German land

Lay round me green and still.

But all day long on the eastern bank

Of the river cool and clear,

Where the curving track of the double rails

Was hardly seen though near,

The endless trains of German troops

Went rolling down to Trier.

They packed the windows with bullet heads

And caps of hodden gray;

They laughed and sang and shouted loud

When the trains were brought to a stay;

They waved their hands and sang again

As they went on their iron way.

No shadow fell on the smiling land,

No cloud arose in the sky;

I could hear the river’s quiet tune

When the trains had rattled by;

But my heart sank low with a heavy sense

Of trouble,- I knew not why.

Then came I into a certain field

Where the devil’s paint-brush spread

‘Mid the gray and green of the rolling hills

A flaring splotch of red,-

An evil omen, a bloody sign,

And a token of many dead.

I saw in a vision the field-gray horde

Break forth at the devil’s hour,

And trample the earth into crimson mud

In the rage of the Will to Power,-

All this I dreamed in the valley of Kyll,

At the sign of the blood-red flower.

– Henry van Dyke

Henry Van Dyke. The Red Flower: Poems Written in War Time (New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1917). 3-4.

At the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, Henry van Dyke (HvD) had been living a charmed life. He was a prominent member of the Presbyterian clergy, a respected Princeton professor, and a widely read author whose fifty-second book, Fighting for Peace, was the aforementioned volume in my possession. He would go on to publish a total of seventy-five books and twenty-two leaflets to his own credit and assist with thirty others. His famous angling titles, Little Rivers (1895), Fisherman’s Luck (1899), and A Creelful of Fishing Stories (1932), earned him an honored position among America’s great angling writers.

In 1913, at the age of sixty-one, HvD had been awarded an ambassadorship to the Netherlands and Luxembourg from former Princeton colleague and then U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. After a few weeks of salmon fishing on Canada’s Ste. Marguerite River, he sailed forth with his family and soon settled into a new home at The Hague during the autumnal splendor of that year. He enjoyed the civility of state affairs, was received by European royalty and other dignitaries, and settled into a well-organized and dutiful routine. President Wilson had charged him with assisting in any way he could with preserving the tenuous state of peace that existed at the time. HvD wrote that “The international sky was clear except for one big cloud, which had been there so long that the world had grown used to it. The Great Powers kept up the mad race of armaments, purchasing mutual terror at the price of billions of dollars every year.”2

In the early summer of 1914, diplomatic affairs brought HvD to Luxembourg, where he also reserved some free time for fishing the tranquil streams of the region.

Having just gone just over the German border for a bit of angling, I was following a very lovely river full of trout and grayling. With me were two or three Luxembourgers and as many Germans, to whom fishing with the fly-fine and far off-was a new and curious sight. Along the east bank of the stream ran one of the strategic railways of Germany from Koln to Trier. All day long innumerable trains rolled southward along that line, and every train was packed with soldiers in field-gray-their cheerful stolid bullet heads stuck out of all the windows. “Why so many soldiers,” I asked, “and where are they all going?” “Ach,” replied my German companions, “it is Pfingstferien (Pentecost vacation) and they are sent a changing of scene and air to get.” My Luxembourger friends laughed. “Yes, yes” they said. “That is it. Trier has a splendid climate for soldiers. The situation is kolossal for that!”

When we passed through the hot and dusty little city, it was simply swarming with the field-gray ones-thousands upon thousands of them-new barracks everywhere; parks of artillery; mountains of munitions and military stores. It was a veritable base of operation, ready for war.

Now the point is that Trier is just seven miles from Wasserbillig on the Luxembourg frontier, the place where the German forces entered the neutral land on August 2,1914.3

During that one fateful day astream, HvD experienced a dark premonition of the events that soon transpired. He was inspired to commit the vision to stirring verse under the title “The Red Flower,” which was published in his 1917 book The Red Flower: Poems Written in War Time.

Henry van Dyke and his family were now thrust center stage into a war that was supposed to end all wars. Diplomatic duties grew exponentially as masses of stranded Americans sought refuge and the safety of U.S. soil. HvD wrote:

We were benumbed and terrified. There was nothing that we could do. The monstrous thing advanced, but even while we shuddered we could not make ourselves feel it was real. It had the vagueness and horrid pressure of a bad dream.

If it seemed dreamlike to us, so near at hand, how could the peo- ple in America, three thousand miles away, feel its reality or grasp its meaning? They could not do it then, and many of them have not done it yet.. .

So the storm signs foreshadowed in fair weather, were fulfilled in tempest, more vast and cruel than the world had ever known . . . Those who loved true peace-peace with equal security for small and great nations, peace with law protecting the liberties of the people, peace with power to defend itself against assault were forced to fight for it or give it up forever.4

ANGLERS IN THE TRENCHES

The European nations and their allies understood what was at stake, and battle lines were expeditiously drawn. In the midst of such chaos, a host of anglers went to war.

The Hardy Brothers factory of Alnwick, England, immediately sent eleven men from their reel shop to various regiments. James Leighton Hardy wrote in The House the Hardy Brothers Built that “by March, 1915, forty-two men had left to put on uniform and by January, 1917, eighty-five out of eighty-eight eligible men had been called up.”5 While those valiant Hardy employees were fighting on the front–where five lost their lives in 1915–the factory commenced production of various armamentaria that included the precious primers that enabled the legendary vickers machine gunners to maintain their steady hail of lead over no-man’s land.

William J. Hardy, son of Hardy Brothers founder William Hardy, served in the machine gun corps. He was wounded after having his horse shot from under him in April 1918 and became a German prisoner of war, He and his fellow soldiers were treated harshly at the hands of their captors, and William once received a vicious blow to the head from the rifle butt of a guard. He later died of an illness, which may or may not have been brought on as a result of lingering effects suffered as a prisoner of war, on 7 February 1928, one month before his son James Leighton Hardy’s first birthday.

William’s cousin Leslie, who “was a keen angler and, before he joined the colours, had been employed at Hardy’s” fared no better.6 He was struck by a bullet in the head and lost an eye. His World War I experiences haunted him until his death in 1940.

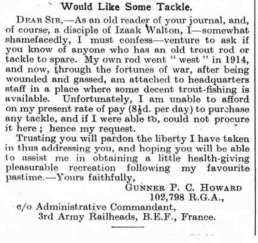

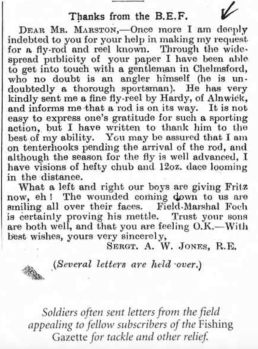

Great Britain’s leading angling publication, the Fishing Gazette, remained in production throughout the war. They established and administered a popular tobacco fund that would provide cigarettes for wounded soldiers. Sadly, their famous publisher, R. B. Marston, would lose a son in the trenches.

The continued publication of that widely read British journal was even lauded on our side of the Atlantic by angling luminary Theodore Gordon: “Notes on the War, etc., from an American Angler.–Mr. Theodore Gordon, one of the best known anglers and angling writers in America, writes to me on Aug. 31,1914: ‘In spite of the greatest war in history and the complete disorganization of commerce the English mails have been arriving regularly and the Fishing Gazette has been delivered to American subscribers.'”7

Other Fishing Gazette headlines and submissions from 1914 give today’s reader a glimpse into the war effort from an anglers’ point of view.

“One horrid result of this war is that one has to think of so many old friends and good sportsmen as enemies because they are Germans or Austrians. If we met on a trout stream now, instead of exchanging flies and drinks, we should have to exchange shots.”8

On The Belgians And The War: “A great many British anglers know trout fishing in the Belgian Ardennes and have friends in Belgium. They must have felt a double sense of relief when the fact that our Expeditionary Force was safely landed at Boulogne was published to the world last Monday, because they know how eagerly the Belgians were looking to Britain and how worthy they are of the best we can do for them.”9

The Rifle for the Rod: Mr. G.E.M. Skues writes:”My Dear Marston, It may be of interest to readers of the Fishing Gazette to know that their friend Louis Bouglk, one of the founders of the Casting Club de France and member of the Fly Fishers’ Club, though just past fifty years of age, and consequently not called up in French mobilisation, thinks in the circumstances, it is the positive duty of every man still capable of marching and firing a rifle to offer his services, so he has enrolled himself as a simple private, volunteering for the period of the war in a regiment of Infantry of the Line in the active army. I am sure we shall all wish him the best of luck and genuine triumph for the French arms.”10

In many instances letters would be sent to the Fishing Gazette directly from the front. Geoffrey Bucknall selected this fascinating letter by tournament caster M. A. P. Decantelle, who was serving in the French army, for inclusion in his 1997 book, The Bright Stream of Memory.

The first couple of months I did not think of fishing. War was a new sport to me, and besides, the Huns were keeping us too busy. The district I was in was thick forest; there was just enough water to drink, so that not only fishing but washing was out of the question.

When we had stopped the German rush, we slowly moved forward again and at last came across the river, a typical trout river. I never wanted to fish so badly. As you are aware, we take turns in the trenches. When the infantry goes to rest some eight to ten miles to the rear of the fighting line, the engineers are always kept in reserve one or two miles from the trenches. The question is to find a beat from which you are not seen by the enemy and not much to attract the gun fire. The river is running almost parallel to our trenches and about two miles from the German trenches. Along the bank are the remains of old German shelters which are handy when the shells come along.

Whether the fishing was preserved before the war I know not. The river is a fine trout stream with every hundred yards a rapid and a pool. Almost every tree has been cut by shells or rifle bullets during the fierce fighting which took place along the river. Most of the branches have fallen across in which have also been thrown vast quantities of barbed wire. As a result, the fishing consists of casting with great accuracy to prevent the trout from getting the line under the wire or sunk branches. I have hooked several beauties on the May Fly, but in every case the result was the loss of the fish, plus fly and part of the cast.

When I do fish it is never more than two or three hours. Where I was fishing the Germans have shelled the river and I was able to make some remarks about the effects of this shelling on the trout. They do not mind shrapnel a bit. One day some newly arrived infantry were playing the fool on the top of the hill and the shrapnel came along on the hill and the river behind. I got under a big stump and from there I could see several trout rising. In spite of the repeated whizz [sic] they kept on rising and when I came out from under my shelter I landed one of them.

As for the heavy (shells) which make fairly large holes in the ground, they give the trout a nasty shock for all instantly go down. The chances of a single man being hit by one of these shells is very small indeed if he lies flat when he hears them coming. I used to remain by the riverside, but found that within 300 yards from the falling point of a heavy shell I was never able to get a bite for a couple of hours, a bit of hard luck for the man who expects to eat fish for supper.

It is surprising to notice the number of men who have never seen fly fishing before. One of them made a funny remark today. As he was staring at my catch I asked him what he thought of it. He replied: “I was thinking you must have been a famous poacher before you joined the army.”

No more fishing for the present. We have moved forward and I am in the forest. The river where I expect to catch my trout is behind the German lines–not for long I hope.11

Bucknall goes on to inform us that Decantelle would later be wounded and eventually receive the prestigious Croix de Guerre for bravery.

R.B. Marston referred to the following letter as “one of the most interesting accounts of fishing at the Front that I have received.”12

STALKING A TROUT FROM A SHELL HOLE ON THE ANCRE. Dear Mr. Marston,- Am just writing to let you know of a little fishing expe- rience I had on the Ancre. Last autumn our regiment did a lot of collecting the dead and burying them on the field, in my opinion the worst job in the war. One day I was sitting under the bank of the river (a clear, fast-running stream about 2 ft. deep generally) eating a bit of bully and biscuit when, ye gods! I saw a trout rise, apparently not worrying about the high explosive that was coming over at the time. Now rations were rather hard and square just then, and as I watched that fish rising I was sorely tempted to sling a bomb at him and get a change of diet, but sportsmanship prevailed, and I devised a way of getting him on the bank. That night, when back at camp, I made a line out of my horses’s tail plaited three thicknesses until I had about 12 ft., and being a very keen fly- fisher, there were some old flies inside my cap, relics of happier days. The next day we were on the same work, and saw that he was rising again. I cut a branch out of one of the ash trees still standing in Blighty Wood, and made a rod about 7ft. long. Armed with this, the line (about which I had my doubts), and a much-worn Hare’s Ear, I stalked that trout as man never did before, worming my way to him through shell holes and debris until I got in a shell hole right on the edge of the stream and about a yard below the fish. A hefty swish in the water told me I had managed to get there without putting him down, so I started to work the rod, and raising my head until I could just see the spot, I lowered the fly. He took it, and I shot out of that shell hole quicker than I went in, and began to play that fish. Luckily for me the stream was only about three yards wide. As he went up the stream I went with him, the ash stick bending to him like a split cane. Up and down we went for about five minutes, until I was able to bring him to the bank. He was a beauty, 15 in., and in good condition. I put him in my haversack; then rolling the cast, that went as usual inside my cap, I left the rod stuck in the ground just where the capture took place, then went and joined my chums, who were just getting ready to resume the gruesome work. The officer asked me where I had been, and when I said fishing, they all burst out laughing, which of course anyone would have done. However, when I pulled out the fish they were surprised, and used some expressions for which our army is noted, the officer at once pro- claiming himself anything but a fly-fisher by wanting to buy it. Needless to say I let him want. When we got back that night there was good news for us. Bread rations had come up, and as I sat frying my trout in a mess tin I wondered if anyone else had done any fishing like that on the Ancre. When I come out of hospital I should like to do a little fishing while convalescent, but army pay is not productive of trout rods and flies-but, well, war is war. I always get the Fishing Gazette, for if one is not able to fish himself it is very inter- esting to hear how the sport is going on. Wishing you the best of luck and continued success with your appreciated paper, -I beg to remain, yours sincerely,

Alan Pye 1154

Trooper A. Pye

1st King Edward’s Horse, K.O.D.R.

A3 Ward, Stoke War Hospital

Stoke-on-Trent, North Staffs13

Not all soldiers and civilians were as sporting as Mssr. Decantelle or Trooper Pye had been. Naturalist Major Anthony Buxton wrote in his 1920 memoir Sport in Peace and War:

Fishing was the only form of sport not discouraged by the authorities on the Western Front. Regulations, often disregarded, were issued against the use of illegal means, such as bombs, nets, and explosives for destroying fish. All the combatants were equally to blame for their destruction of fish by these means, and the rivers of France and Belgium suffered and deteriorated from indiscriminate bombing and netting on both sides of the line by civilians and military during the war.

The legitimate means of fishing, however much employed, did not do very much harm, for trout become quickly educated to a sufficiently high standard to escape destruction.14

Buxton’s personal angling tactics were of the more sporting type.

Military duties when not in the line seldom entailed work after 4 P.M., and though they often interfered with the morning rise, the evening was ours to give to the trout.

If a trout stream was reasonably near, there were few evenings in the summer on which I did not “warn out” for mess; perhaps it would be better to say there were few evenings on which I “warned in.” The first occasion on which I went fishing at the war was in the early spring of 1915 . . . we reached the charming valley of the Course, with its rich meadows, quiet woods, and sparkling clear stream. It was too early in the season for the trout to be very evident, but we did not go back quite empty-handed, or without dis- covering where to come on a later visit …

A second visit to the Course with my Second-in-Command in May was more productive. We slept at Beussent, and had two delightful days, in which twenty-eight trout were caught and an appetite for fishing, not yet appeased, was aroused in my friend.

The trout rose freely to a fine hatch of small duns all over the river, which was much faster than most chalk streams, and presents great difficulties in the matter of ‘drag,’ owing to the pace and the sudden turns of the stream. The fish were not very large, but their appearance and their flavour as presented by our very kind hostess at the inn were altogether excellent.15

Buxton foresaw the day when it would be likely “that many Englishmen who have discovered pleasant streams during the war will go with their friends to re-visit old haunts in times of peace. They will find a pleasant welcome in a delightful coun- try, and if they go to the right places at the right time, they will have fine sport.”16

WADING ON THE DIPLOMATIC FRONT

In July 1914, Sir Edward Grey, a member of the London Flyfishers’ Club, and then British secretary for foreign affairs, made several worthy attempts to slow the tide of the ever- expanding war. His ideas were embraced by King George V, who made a direct appeal to Prince Henry of Prussia, but to no avail. Henry van Dyke’s wartime diplomatic duties required him to return to Luxembourg in April 1915. He wrote an account of the event in an essay titled “Fishing in Strange Waters.”

The second trip was in 1915, after Germany’s long crime had begun. It was necessary for the American Minister to go down to take charge of certain British interests in Luxembourg-a few poor people who had been stranded there and who sorely needed money and help. (What a damned inhuman thing war is, no one knows who has not been in the midst of it) …The journey was interesting. The German Minister at The Hague was most polite and obliging in the matter of providing a visé for the passports and giving the needful papers with big seals to pass the guards in what was euphemistically called “German-occupied territory.” It grated on my nerves, but it was the only way…

One day was passed with my friend the notary Charles Klein, of the old town of Wiltz, a reputable lawyer and a renowned, impassioned fisher. He led us, with many halts for refreshment at wayside inns, to the little river Sure, which runs through a deep flowery vale from west to east, across the Grand Duchy.

Our stretch of water was between the high-arched Pont de Misére and the abandoned slate-quarry of Bigonville. The stream was clear and lively, with many rapids but no falls. It was about the size of the Neversink below Claryville, but more open. The woods crept down the steep, enfolding hills, now on this side, now on that, but never on both. One bank was always open for long casting, which is a delight. The brown trout (Salmo fario), were plentiful and plump, running from a quarter of a pound to a pound weight. Larger ones there must have been, but we did not see them. They accepted our tiny American flies-Beaverkill, Cahill, Queen of the Water, Royal Coachman, and soon-at par value without discount for exchange. It was easy, but not too easy, to fill our creels …

The second day of this series that I remember clearly was spent on a smaller stream, north of the Sure, with Mr. Le G., the son of the British Consul, and other pleasant companions. The name of the stream is forgotten, but the clear water and the pleasant banks of it are “in my mind’s eye Horatio.” It was a meadow-brook very like the one that I know not far from Norfolk, Connecticut, whither I have often gone to fish with my good friend the village storekeeper, S. Cone.

Now there is in all the world no water more pleasant to fish than a meadow-brook, provided the trout are there. The casting is easy, the wading is light, the fish are fat, the flowers of the field are plenteous, and the birds are abundant and songful. We filled our baskets, dined at the wayside inn, a jolly company, and motored back by moonlight to the city of Luxembourg.17

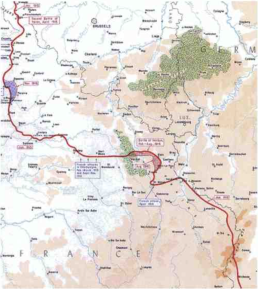

Section of a military map titled “Northwest Europe 1914, Stabilized Front, Major Ofensives and Changes, January 1915-December 1916.” Note the close proximity of Luxembourg to Trier and Verdun. The Grand Duchy was a small county caught in the eye of the storm. Courtesy of United States Military Academy, website www.usma.edu

In May of 1916, HvD returned to his “outlying post” of Luxembourg and once again traveled through the German town of Trier where “hundreds of thousands of green-gray soldiers were rushing on their way to the Battle at Verdun.”18 In Luxembourg he mentioned that “no longer did the field-gray ones sing when they marched, as they used to do in 1915. They plodded silent, evidently depressed. The war which they had begun so gayly [sic] was sinking into their souls. The first shadows of the Great Fatigue were falling upon them; but lightly as yet.”19

With the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg away at her summer castle, HvD addressed some local affairs and then “was free to turn to the streams” with his host, Emile Meyrisch, an ironmaster and “an angler of the most confirmed sect.”20

He took me to the valley of the Clerf; the loveliest little river in Luxembourg. By ruined castles and picturesque villages, among high-shouldered hills and smooth green meadows and hanging woods it runs with dancing ripples, long curves, and eddying pools where the trout lurk close to the bank . . . The Clerf runs from north to south. I suppose that was why the south wind, on that quiet sunny morning, carried into the placid valley a strange continuous rumbling like very distant thunder . . . Undoubtedly it was the noise of the guns in the offensive Crown Prince’s “Great Offensive” at Verdun, a hundred kilometers away.

Strange that a sound could travel so far! Dreadful to think what it meant! It crossed the beauty of the day. But what could one do? Only fish on, and wait, and work quietly for a better day when America should come into the war and help to end it right.

A very fat and red-faced Major, whom I had met before at Clerveaux, rode by in a bridle path through the meadow. He stopped to salute and exchange greetings.

“How goes it?” I asked.

“Verdamt schlecht,” he replied. “This is a dull country. The people simply won’t like us. I wish I was at home.”

“I too!” I answered.21

After America’s eventual entry into the Great War, Germany would be subdued and the League of Nations established to enforce a lasting peace. The world had survived the war to end all wars. Henry van Dyke viewed the events pragmatically when he asked “would the organization of such a league of nations to defend peace make war henceforward impossible? No sane man, who knows the ignorance, the imperfection, the passionate frailty of human nature entertains such a wild dream or makes such an extravagant claim. All that the league can hope to do is to make an aggressive war, such as Germany thrust upon the world in 1914, more difficult and more dangerous.22

A RETURN TO ARMS

The League of Nations may have been a noble concept but sadly, fewer than twenty-five years after the armistice, Ernest Hemingway’s twenty-year-old son, Jack, was awaiting the order that would launch him out into the dark wartime skies over France. Their airborne mission was being carried out in part to set up a communications network, track the movements of the 11th Panzer Division, and provide training for the local resistance. In his 1986 autobiography, Misadventures of a Fly Fisherman, he describes a unique aspect of his premission anxiety: “I began to fret about how I was going to get away with bringing my fly rod, reel, and box of flies. I had managed to keep them with me ever since I became an officer and I was damned if I was going to leave them behind. It might even be bad luck”23 When his rod was spotted by a British officer he was told, “You can’t bring THAT with you, you know.” The cool-headed Hemingway replied, “Oh, it’s only a special antenna. Just looks like a fly rod.”24

When it finally came time to jump, Hemingway recalled the moment:

I grasped my fly rod by the center in my right hand, prepared to bring it parallel to my rigid body as I readied myself to stand at attention going out the hole. The red light was on and I couldn’t help tensing. It switched to green and the dispatcher hit Jim’s shoulder and, as soon as he was out, mine, and I was gone.

Never have I felt a greater sense of jubilation. After a short moment of total disorientation, the chute had opened with a snap and I was alive in what seemed total silence as the sound of the engines faded away. 25

After moving off into the French countryside, Captain Hemingway would soon learn of the successful D-Day landings via BBC radio. His first opportunity, or perhaps impulse, to go fishing came immediately after wiping tears of sorrow from his eyes: he had just viewed the brutally massacred and mutilated corpses of more than a dozen French teenage resistance fighters who had been trapped in a railroad tunnel by the Nazis and were afforded no rights under the Geneva Convention. Any physical or emotional escape that the river may have provided the traumatized captain was to be short-lived.

I was in khaki, a civilian garb not uncommon at the time, but wore no cap and there was a U.S. flag sewn to my right soldier, but no insignia on the left. I wore the shoulder holster and a .38 inside my OD shirt. I fastened the reel onto the rod butt, left the rod case behind, and stuck the fly box and leader damping case inside my shirt beneath the pistol …Nervous at first, I had finally been over- come by the joy of going fishing. Despite the incongruity of the circumstances, I broke into a wild, leaping run down the mountain- side, totally oblivious of the risk of life and limb…

I hunkered down and kept my casts horizontal, to fish out the tail of the pool where the water roughened a bit before leaving the pool for a short series of chutes down to the next steep water. I had become totally concentrated on thoroughly covering the last few yards of possible holding water when I heard a most unwelcome and frightening sound, that of marching boots close by. With the sound of the stream through the nearby riffles, I had been caught completely unaware. I looked up and, marching at route step with rifles and machine pistols at sling arms, was a patrol in German uniform. They were all looking toward me and making what sounded like derisive, joking comments as they went along.

For the first time in my life I made a silent wish that came as close to a real prayer as I had ever come. Above all, I wished not to hook a fish at that moment. If I had, the whole patrol would have halted to watch. Then there would have been a conversation and, if I had turned to any degree, the U.S. flag would have been visible. The powers above were with me; I hooked nothing, and the Germans kept marching down the track.26

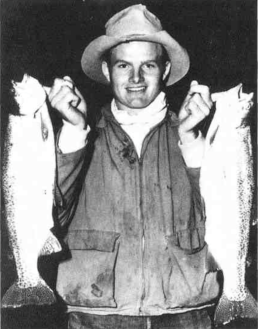

Captain Jack would return from the war and lead an active sporting life right up until his death in 2000, I had the pleasure of sitting next to him for lunch one afternoon during the holiday season of 1999 and count myself truly fortunate to have met him.

CONFLICTING EMOTIONS

In the lingering aftermath of the September 11th tragedy, I found myself in a numbed state of confusion and dismay. Realizing that similar emotions were being felt throughout North America and abroad, I could not find solace on my favorite stream or in my cherished sporting books. “How could I think of fishing at a time like this?” echoed over and over again in my thoughts. I later discovered that these very thoughts have been examined by others.

Jack Hemingway obviously had no trouble reconciling his thoughts about fishing and fighting. He did both very well.

Henry van Dyke anticipated the question when he asked, “Why does this foolish writer talk about silly things like fishing while the world-war was going on, and especially now that the great social problems of the new era must be solved at once? He is a trifler, a hedonist, a man devoid of serious purpose and strenuous effort . . .”27

But rather than wallow in self-guilt, HvD embraced the idea of going fishing in times of trial: “I hold by the advice of the Divine Master who told his disciples to go a-fishing; and said to them when they were weary, ‘Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place and rest awhile.'”28 He had been to the front lines to “taste the cup of danger” and recalled “soldiers whom I saw deliberately fishing on the banks of the Marne and Meuse while the guns roared around us.”29 He believed “that the most serious men are not the most solemn” and “that a normal human being needs relaxation and pleasure to keep him from strained nerves and a temper of fanatical insanity”30 He chose the recreation of angling for four reasons: “First because I like it; second, because it does no harm to anybody; third, because it brings me in touch with Nature, and with all sorts and conditions of men; fourth, because it helps me to keep fit for work and duty.”31

The debate was also carried out in the pages of the Fishing Gazette as well. “Is it unpatriotic to Fish, Hunt or Shoot in Wartime?-Providing that doing so does not militate against military or other duty, then it is quite certain to fish, or hunt, or shoot, or to engage in outdoor sports is neither unpatriotic or undesirable.”32 They added that Wellington hunted during the war with France in 1813, and that Izaak Walton “was faithful to angling through long times of trouble.”33

Sir Edward Grey would go on to become Viscount Grey of Fallodon, and author of the famous Fallodon Papers of 1926, in which his timeless essays on fly fishing and recreation have been preserved for posterity. He wrote:

In those dark days I found some support in the steady progress unchanged of the beauty of the seasons. Every year, as spring came back unfailing and unfaltering, the leaves came out with the same tender green, the birds sang, the flowers came up and opened, and I felt that a great power of Nature for beauty was not affected by the war. It was like a great sanctuary into which we could go and find refuge for a time from even the greatest trouble of the world, finding there not enervating ease, but something which gave optimism, confidence, and security.34

Endnotes

An elated Jack Hemingway in mufti enjoying the sport he loved most. Photo courtesy of Angela H. Hemingway

ENDNOTES

- Henry van Dyke, Fighting for Peace (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), 197-198.

- Ibid., 20-21.

- Ibid., 36-37.

- Ibid., 45-47.

- James Leighton Hardy, The House the Hardy Brothers Built (Ashburton, Devon, England: The Flyfisher’s Classic Library, 1998), 61.

- Ibid., 20.

- The Fishing Gazette, 19 September 1914, 267.

- The Fishing Gazette, 17 October 1914, 367 (footnote).

- The Fishing Gazette, 22 August 1914, 195.

- The Fishing Gazette, 25 August 1914, 177.

- . M.A.P. Decantelle, 31 July 1915, in Geoffrey Bucknall, The Bright Stream of Memory (Shrewsbury, England: Swan Hill Press, 1997), 63.

- The Fishing Gazette, 9 June 1917, 309.

- Ibid.

- Anthony Buxton, Sport in Peace and War (London: Arthur Humphreys, 1920), 1.

- Ibid., 24.

- Ibid., 13.

- . Henry van Dyke, “Fishing in Strange Waters,” Camp-Fires and Guideposts (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1y21),123-129.

- Ibid., 129.

- Ibid., 130.

- Ibid., 131.

- Ibid., 131-133.

- van Dyke, Fighting for Peace, 245.

- Jack Hemingway, Misadventures of a Fly Fisherman (Dallas, Tex.: TaylorPublishing Company, 1986),137.

- Ibid., 138.

- Ibid., 139-40.

- Ibid., 146-47.

- van Dyke, “Fishing in Strange Waters,” 140.

- Ibid., 140.

- Ibid., 141.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Fishing Gazette, 19 September 1914, 267.

- Ibid.

- Viscount Grey of Fallodon, K.G., Fallodon Papers (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926), 79.